John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan

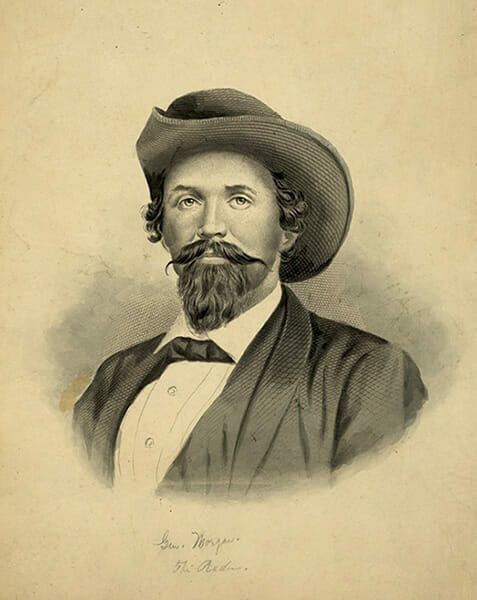

Alabama native John Hunt Morgan (1825-1864) was a merchant and military officer who served in the U.S. Army and Kentucky Militia during the Civil War. He earned the nickname “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy” as he raided from Tennessee into Kentucky and Ohio between the spring of 1862 and the summer of 1864, taking prisoners and equipment and disrupting federal supply lines. Men under his command engaged in pillaging on several occasions, and he was suspended from command in August 1864 shortly before he was killed while evading capture by U.S. forces.

John Hunt Morgan

Alabama native John Hunt Morgan (1825-1864) was a merchant and military officer who served in the U.S. Army and Kentucky Militia during the Civil War. He earned the nickname “Thunderbolt of the Confederacy” as he raided from Tennessee into Kentucky and Ohio between the spring of 1862 and the summer of 1864, taking prisoners and equipment and disrupting federal supply lines. Men under his command engaged in pillaging on several occasions, and he was suspended from command in August 1864 shortly before he was killed while evading capture by U.S. forces.

Morgan was born June 1, 1825, in Huntsville, Madison County, the oldest of ten children of Calvin and Henrietta (Hunt) Morgan. After Calvin’s pharmacy failed, the family relocated to Lexington, Kentucky, in 1831, where Henrietta had roots. Morgan’s maternal grandfather, John Wesley Hunt, was an early founder of Lexington and later a wealthy businessman. Morgan grew up on one of the Hunt farms, where he learned to shoot and ride horses. He obtained his early education at home and at nearby schools, and he attended local Transylvania College from 1842 to 1844 but was expelled for challenging a fraternity brother to a duel. He became a Freemason in 1846 and shortly thereafter enlisted in Capt. Oliver P. Beard’s company of Col. Humphrey Marshall’s Volunteer Cavalry Regiment during the Mexican-American War. He later was elected first lieutenant and fought at the Battle of Buena Vista, in Coahuila, Mexico, in February 1847. After his return to Lexington on November 21, 1848, he married Rebecca Gratz Bruce; the couple would have one child who died at birth. Morgan then acquired land, purchased slaves, opened a clothing factory with his brother Calvin, and became prosperous manufacturing hemp rope and bagging.

In a practice common to men of his high social standing, Morgan raised a militia artillery company in 1852 that the state legislature disbanded two years later. In 1857, he raised an infantry company known as the “Lexington Rifles.” Morgan backed Kentuckian and Vice President John C. Breckenridge, the Southern Democrat candidate, in the 1860 presidential election and did not initially support Kentucky’s secession. But he flew a Confederate flag above his factory in Lexington after the attack on Fort Sumter, which marked the start of the Civil War. He attended to his ailing wife until she died on July 21, 1861. The following September, his militia company joined the Confederate Army at Camp Boone in Tennessee. Morgan appointed to the rank of captain and sworn into the Confederate Army on October 27, 1861. He hoped to bring Kentucky into the Confederacy.

Morgan’s Raiders

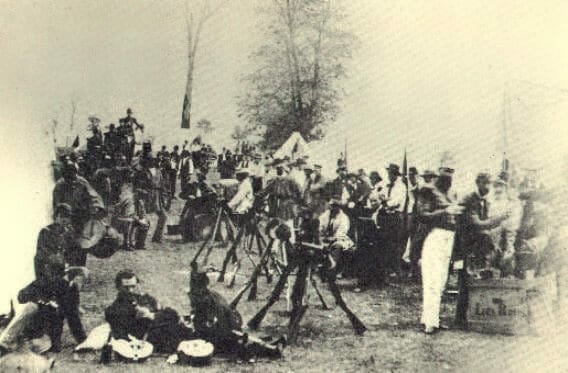

Morgan was promoted to colonel of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, known as “Morgan’s Raiders,” on April 4, 1862. Two days later, his unit, along with the Texas Rangers Cavalry, participated in a charge at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee and engaged federal forces again at Fallen Timbers along the Corinth Road on April 8. Soon attached to Gen. Joseph Wheeler‘s division under Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Tennessee, Morgan began a three-week raid on July 4 with 900 soldiers that covered 1,000 miles into Kentucky. Bragg hoped Morgan would serve as the rearguard and draw the U.S. cavalry to assist in concealing the movements of his invasion of Kentucky. By August 1, the raiders had destroyed telegraph and railroad lines and captured 1,200 federal soldiers and some 300 hundred horses, as well as medical stores, tents, weapons, and ammunition. On September 4, 1862, Morgan, now in command of a brigade, raided into northern Kentucky in support of a major Confederate offensive. On October 7, the unit attacked a federal garrison at Hartsville, Tennessee, and overwhelmed a U.S. military encampment at Ashland, Kentucky, on the morning of October 18, where it captured and paroled 290 federal soldiers.

Morgan’s Raiders

Morgan was promoted to colonel of the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment, known as “Morgan’s Raiders,” on April 4, 1862. Two days later, his unit, along with the Texas Rangers Cavalry, participated in a charge at the Battle of Shiloh in Tennessee and engaged federal forces again at Fallen Timbers along the Corinth Road on April 8. Soon attached to Gen. Joseph Wheeler‘s division under Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Tennessee, Morgan began a three-week raid on July 4 with 900 soldiers that covered 1,000 miles into Kentucky. Bragg hoped Morgan would serve as the rearguard and draw the U.S. cavalry to assist in concealing the movements of his invasion of Kentucky. By August 1, the raiders had destroyed telegraph and railroad lines and captured 1,200 federal soldiers and some 300 hundred horses, as well as medical stores, tents, weapons, and ammunition. On September 4, 1862, Morgan, now in command of a brigade, raided into northern Kentucky in support of a major Confederate offensive. On October 7, the unit attacked a federal garrison at Hartsville, Tennessee, and overwhelmed a U.S. military encampment at Ashland, Kentucky, on the morning of October 18, where it captured and paroled 290 federal soldiers.

John and Mattie Morgan

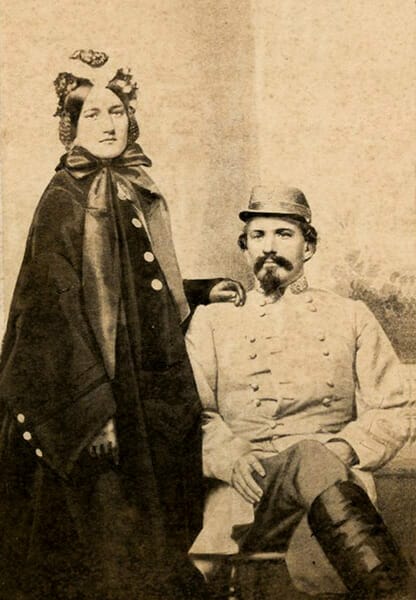

Morgan was promoted to brigadier general on December 13 and would take command of a cavalry division. The following day, he married Martha “Mattie” Ready, the daughter of Charles Ready, a former congressman from Tennessee. Confederate president Jefferson Davis and other dignitaries attended the wedding. The couple would have a daughter, Johnnie Hunt Morgan, who was born after his death. From December 22 to January 5, Morgan and 4,000 soldiers patrolled the Green River region in south-central Kentucky, disrupted the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and federal supply lines, defeated U.S. forces at Elizabethtown, Tennessee, on December 27, and destroyed the Big South Tunnel north of Gallatin, Tennessee. This venture came to be known as the “Christmas Raid.” Morgan returned a hero and received a congratulatory vote from the Confederate Congress on May 17, 1863, for his exploits.

John and Mattie Morgan

Morgan was promoted to brigadier general on December 13 and would take command of a cavalry division. The following day, he married Martha “Mattie” Ready, the daughter of Charles Ready, a former congressman from Tennessee. Confederate president Jefferson Davis and other dignitaries attended the wedding. The couple would have a daughter, Johnnie Hunt Morgan, who was born after his death. From December 22 to January 5, Morgan and 4,000 soldiers patrolled the Green River region in south-central Kentucky, disrupted the Louisville and Nashville Railroad and federal supply lines, defeated U.S. forces at Elizabethtown, Tennessee, on December 27, and destroyed the Big South Tunnel north of Gallatin, Tennessee. This venture came to be known as the “Christmas Raid.” Morgan returned a hero and received a congratulatory vote from the Confederate Congress on May 17, 1863, for his exploits.

Morgan then was ordered to undertake an ambitious campaign that became known as “Morgan’s Raid.” The endeavor had several purposes, including diverting federal forces away from Gen. Robert E. Lee’s offensive into the North and from their siege of Confederate forces hemmed in at Vicksburg, Mississippi, distracting federal attention from Bragg’s withdrawal, and determining the U.S. military’s response to a Confederate invasion of the North. Morgan departed McMinnville, Tennessee, with 2,462 cavalrymen and a battery of light artillery on June 11, 1863. The force captured two steamboats in Brandenburg, Kentucky, that it used to transport troops across the Ohio River to Mauckport, Indiana. In July, the force engaged in a skirmish at Corydon, Indiana, and the Confederate troops looted county and city treasuries in Versailles, Indiana. But when Morgan learned that some of his men stole jewels from the local masonic lodge, he intervened, recovered the stolen property, and returned it the following day. Morgan’s raiders captured and paroled nearly 6,000 U.S. soldiers and damaged some $10 million worth of property. On July 19, 750 of his men were captured at Buffington Island, Ohio, while trying to cross the Ohio River into West Virginia. After the Battle of Salineville in Ohio, Morgan and his remaining 350 cavalrymen were captured on July 26 at nearby West Point, Ohio. It was the farthest incursion of any uniformed Confederate troops into U.S. territory during the war, although the raid had violated orders to avoid crossing the Ohio River. Ultimately, it has been seen as a failure, as Lee’s army was roundly defeated at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3 and Vicksburg surrendered the following day.

Ohio Penitentiary

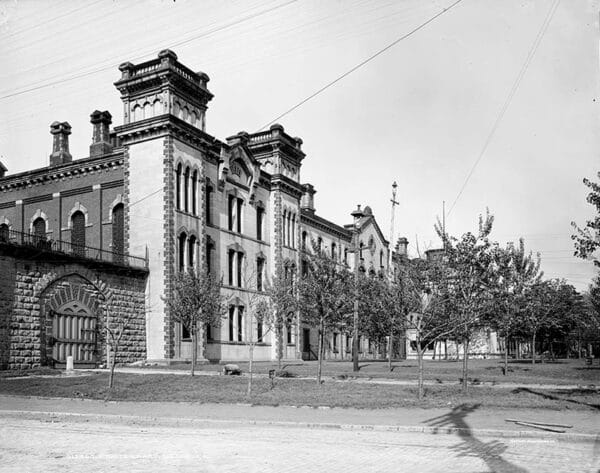

Morgan and his officers were imprisoned in the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio, where he was placed in solitary confinement and reportedly nearly starved to death. On November 27, 1863, he and six of the officers escaped their cells by tunneling into the inner prison yard, where they climbed over the prison wall, aided by an improvised rope made by Morgan. He and three other officers donned civilian clothes and boarded a train bound for Cincinnati, Ohio, but jumped off before reaching the depot. They escaped across the Ohio River into Kentucky aboard a skiff operated by southern sympathizers. Morgan reunited with his wife in Columbia, South Carolina, before traveling to the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. There, Morgan was honored with a parade and praised by the Virginia legislature.

Ohio Penitentiary

Morgan and his officers were imprisoned in the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio, where he was placed in solitary confinement and reportedly nearly starved to death. On November 27, 1863, he and six of the officers escaped their cells by tunneling into the inner prison yard, where they climbed over the prison wall, aided by an improvised rope made by Morgan. He and three other officers donned civilian clothes and boarded a train bound for Cincinnati, Ohio, but jumped off before reaching the depot. They escaped across the Ohio River into Kentucky aboard a skiff operated by southern sympathizers. Morgan reunited with his wife in Columbia, South Carolina, before traveling to the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. There, Morgan was honored with a parade and praised by the Virginia legislature.

The following spring, Morgan assumed command of the Military Department of Southwest Virginia to defend salt works and lead mines. Some of his soldiers conducted raids throughout the summer into east Tennessee and Kentucky, essentially pillaging and inflicting numerous civilian casualties. On June 8, 1864, soldiers robbed a bank in Mount Sterling, Kentucky, of $72,000. Throughout August 1864, Morgan attempted to clear his name from an impending court-martial for not investigating the robbery and, on August 30, he was suspended from command by the Confederate War Department. Nonetheless, on September 3, Morgan and his men arrived in Greeneville, Tennessee, where they established headquarters.

John Hunt Morgan Memorial

In the early hours of September 4, 1864, federal cavalry raided the town, and Morgan was shot as he resisted capture in a garden outside the house. His death was lauded in the North and lamented in the South. Federal soldiers abused his corpse and paraded it to their headquarters. The following day, his body was transported under a flag of truce to his wife in Abingdon, Virginia, where his first funeral was held. A week later, thousands of mourners attended a state funeral in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. In 1868, Morgan’s brother transported his body back to Lexington, where nearly 2,000 people attended a third funeral at Lexington Cemetery on April 17, 1868.

John Hunt Morgan Memorial

In the early hours of September 4, 1864, federal cavalry raided the town, and Morgan was shot as he resisted capture in a garden outside the house. His death was lauded in the North and lamented in the South. Federal soldiers abused his corpse and paraded it to their headquarters. The following day, his body was transported under a flag of truce to his wife in Abingdon, Virginia, where his first funeral was held. A week later, thousands of mourners attended a state funeral in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. In 1868, Morgan’s brother transported his body back to Lexington, where nearly 2,000 people attended a third funeral at Lexington Cemetery on April 17, 1868.

Morgan’s legacy has been preserved by historic markers, statues, and landmarks as well as through historic trails, school mascots, and in song. In 2009, the Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy dedicated a grave marker in the Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville; a statue of Morgan that once stood in front of the Madison County Courthouse was relocated to the cemetery in 2020. Morgan’s birthplace, the Hunt-Morgan House in Huntsville’s Twickenham Historic District, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and also bears a historic marker; it houses a Civil War museum. Lexington features several Morgan-themed landmarks, including an equestrian statue located at one corner of the old Fayette County Courthouse. Several high schools in Indiana and Ohio named their teams the “Raiders” in his honor.

Further Reading

- Black Robert W. Ghost, Thunderbolt, and Wizard: Mosby, Morgan, and Forrest in the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books, 2008.

- Mowery, David L. Morgan’s Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio. Charleston: The History Press, 2013.

- Ramage, James A. Rebel Raider: The Life of General John Hunt Morgan. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1986.

- Thomas, Edison H. John Hunt Morgan and His Raiders. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1975.