Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African American pilots in U.S. military service, and the only ones in World War II. They became known as the Tuskegee Airmen because all of them received their primary, basic, and advanced pilot training near the city of Tuskegee, Macon County. The term has come to be applied not only to the almost 1,000 black pilots, but also to approximately 13,600 other personnel who served with them in various Army Air Forces organizations, including armorers, bombardiers, engineers, navigators, and maintenance and supply personnel. The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II successfully fought two wars, one against overseas enemies, and one against racism within the American military.

Unease in the late 1930s over possible war between Europe and Asia prompted the federal government to expand its air defenses and the civilian pilot training program, which was open to African Americans. However, it was a commonly held view among whites prior to World War II that blacks could not make good pilots, and thus they were not allowed to fly in the military. But the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the black press successfully advocated for a greater role for blacks in America’s military. Most Tuskegee Airmen were not in the military before their training at Tuskegee began; many joined the program because they did not want to serve on the ground and wanted to be officers rather than enlisted personnel. To be considered for pilot training at Tuskegee, potential candidates had to be college graduates and were expected to be officers in the Army Air Forces, usually second lieutenants, as they completed their advanced training. Because Tuskegee was the only training facility for black pilots in the American military during World War II, potential pilots came from all over the country.

Each of the black military pilots passed through a sequence of flying training phases. The first of these was civilian pilot training (CPT), which began in 1940 at Tuskegee Institute (present-day Tuskegee University) and also took place at various other institutions around the country. After CPT, the men began primary pilot training in 1941 at Tuskegee’s nearby Moton Field under contract with the Army Air Forces using Army PT-17 and PT-13 biplanes and PT-19 monoplanes. Following primary flight training, the pilot cadets moved in November 1941 to a much larger airfield between Tuskegee and Tallassee, Elmore County, called Tuskegee Army Air Field, an Army Air Forces installation, where they underwent the next three phases of training. Basic flying training took place using BT-13 airplanes, followed by advanced flying training with AT-6 aircraft. The last stage was transition training, using the P-40 fighter aircraft used in combat during World War II or twin-engine AT-10 aircraft for those who anticipated flying B-25 bombers.

Noel Parrish

During most of the war, Col. Noel Parrish, a white man, served as commander at Tuskegee Army Air Field and its flying school. His staff included both black and white personnel; according to pilots who trained at the field, Parrish was a fair commander who seemed genuinely interested in their success and allowed the air field’s officers’ club to admit black officers. The presence of black officers in the area did cause some friction in the nearby town of Tuskegee when the officers went into town, however.

Noel Parrish

During most of the war, Col. Noel Parrish, a white man, served as commander at Tuskegee Army Air Field and its flying school. His staff included both black and white personnel; according to pilots who trained at the field, Parrish was a fair commander who seemed genuinely interested in their success and allowed the air field’s officers’ club to admit black officers. The presence of black officers in the area did cause some friction in the nearby town of Tuskegee when the officers went into town, however.

Standards were high at Tuskegee, and many prospective pilots did not graduate from all the phases of training there, and did not ultimately become combat pilots in World War II. The first African American flying unit was the 99th Pursuit Squadron, later designated as the 99th Fighter Squadron. It was first activated at Chanute Field, Illinois, on March 22, 1941, and moved to Tuskegee in November. The unit’s first black pilots graduated from advanced training at Tuskegee Army Air Field in March 1942 and included Benjamin O. Davis Jr. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Davis went on to become the commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron. Soon, three other fighter squadrons were activated at Tuskegee, including the 100th, 301st, and 302nd, and were assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group.

Tuskegee Airmen at Ramitelli, Italy

In the spring of 1943, the 99th Fighter Squadron deployed from Tuskegee to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, arriving in Casablanca, French Morocco, in April as the campaign in North Africa was ending. Meanwhile, the 332nd Fighter Group and its three fighter squadrons moved to Selfridge Field, Michigan, to continue combat training. Flying P-40 aircraft for the Twelfth Air Force, the 99th was attached at various times to different fighter groups flying patrol and bomber escort missions and attacking enemy targets on the ground on the Italian islands of Pantelleria and Sicily and the Italian mainland. Although its performance was questioned by other fighter groups, a War Department study determined that the 99th was flying at least as well as the other P-40 squadrons with which it served. It earned its first Distinguished Unit Citation, along with the group with which it served, while flying missions over Sicily in June and July 1943 in preparation for the Allied invasion there. On July 2, 1943, several notable events occurred. The Ninety-ninth earned its first aerial victory when 1st Lt. Charles B. Hall shot down a FW-190 aircraft and the squadron lost its first pilots in combat, 1st Lt. Sherman H. White and 2d Lt. James L. McCullin, who went missing in action. The unit was transferred to Licata, Sicily, in July 1943. After the Allies landed at Anzio, Italy, in late January 1944, the 99th shot down 13 enemy airplanes in two consecutive days, January 27-28, 1944, while protecting Allied ground forces from enemy air attack. The 99th earned a second Distinguished Unit Citation flying missions against enemy targets over Cassino, Italy, on May 12-14, 1944, along with the white group to which it was attached.

Tuskegee Airmen at Ramitelli, Italy

In the spring of 1943, the 99th Fighter Squadron deployed from Tuskegee to the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, arriving in Casablanca, French Morocco, in April as the campaign in North Africa was ending. Meanwhile, the 332nd Fighter Group and its three fighter squadrons moved to Selfridge Field, Michigan, to continue combat training. Flying P-40 aircraft for the Twelfth Air Force, the 99th was attached at various times to different fighter groups flying patrol and bomber escort missions and attacking enemy targets on the ground on the Italian islands of Pantelleria and Sicily and the Italian mainland. Although its performance was questioned by other fighter groups, a War Department study determined that the 99th was flying at least as well as the other P-40 squadrons with which it served. It earned its first Distinguished Unit Citation, along with the group with which it served, while flying missions over Sicily in June and July 1943 in preparation for the Allied invasion there. On July 2, 1943, several notable events occurred. The Ninety-ninth earned its first aerial victory when 1st Lt. Charles B. Hall shot down a FW-190 aircraft and the squadron lost its first pilots in combat, 1st Lt. Sherman H. White and 2d Lt. James L. McCullin, who went missing in action. The unit was transferred to Licata, Sicily, in July 1943. After the Allies landed at Anzio, Italy, in late January 1944, the 99th shot down 13 enemy airplanes in two consecutive days, January 27-28, 1944, while protecting Allied ground forces from enemy air attack. The 99th earned a second Distinguished Unit Citation flying missions against enemy targets over Cassino, Italy, on May 12-14, 1944, along with the white group to which it was attached.

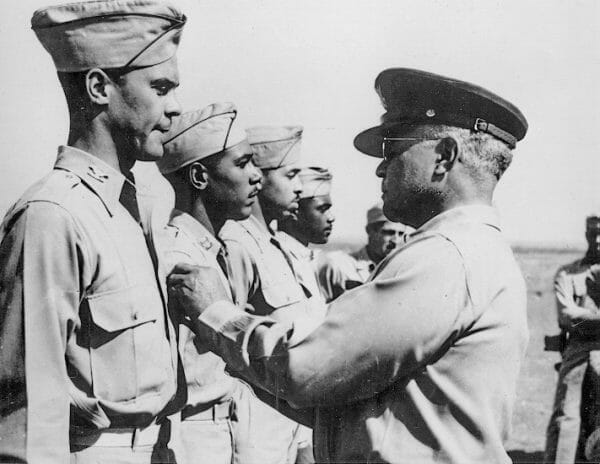

Benjamin O. Davis Receives Distinguished Flying Cross

Davis, who had commanded the 99th Fighter Squadron in combat, returned to the United States to assume command of the 332nd Fighter Group in September 1943. Early in February 1944, the group arrived in Italy. (Although the 332nd served in the Twelfth Air Force like the 99th Fighter Squadron, the 99th was not immediately assigned to it until May 1944, but operated under other fighter groups until June, flying mostly ground attack missions.) The group flew P-39 fighters and attacked enemy ground targets in support of Army ground forces in central Italy. In June 1944, the 332nd was reassigned from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Air Force and stationed at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy, on the Adriatic coast about midway up the Italian peninsula. The unit also was given a new mission: escorting B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers on missions deep into enemy territory, including Germany. During that first month of bomber escort duty, the 332nd Fighter Group flew P-47 Thunderbolts, but in July it switched to the faster and longer-range P-51 Mustangs, the best U.S. fighter planes of the war. During that same month, the 99th Fighter Squadron moved to Ramitelli and traded its P-40s for P-51s.

Benjamin O. Davis Receives Distinguished Flying Cross

Davis, who had commanded the 99th Fighter Squadron in combat, returned to the United States to assume command of the 332nd Fighter Group in September 1943. Early in February 1944, the group arrived in Italy. (Although the 332nd served in the Twelfth Air Force like the 99th Fighter Squadron, the 99th was not immediately assigned to it until May 1944, but operated under other fighter groups until June, flying mostly ground attack missions.) The group flew P-39 fighters and attacked enemy ground targets in support of Army ground forces in central Italy. In June 1944, the 332nd was reassigned from the Twelfth to the Fifteenth Air Force and stationed at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy, on the Adriatic coast about midway up the Italian peninsula. The unit also was given a new mission: escorting B-17 and B-24 heavy bombers on missions deep into enemy territory, including Germany. During that first month of bomber escort duty, the 332nd Fighter Group flew P-47 Thunderbolts, but in July it switched to the faster and longer-range P-51 Mustangs, the best U.S. fighter planes of the war. During that same month, the 99th Fighter Squadron moved to Ramitelli and traded its P-40s for P-51s.

The 332nd Fighter Group was one of seven fighter escort groups in the Fifteenth Air Force; each of its four P-51 fighter squadrons had distinctively painted red tails, to distinguish them from other groups during mass formation missions. The 332nd and its planes then were sometimes called the “Red Tails” by the Airmen themselves as well as bomber pilots and other escorts. Of the 311 combat missions that the 332nd Fighter Group flew for the Fifteenth Air Force, 179 escorted bombers. On only seven of those bomber escort missions were Tuskegee Airmen-escorted bombers downed by enemy airplanes. A total of 27 Tuskegee Airmen-escorted bombers were shot down by enemy airplanes, but this compared favorably with the other Fifteenth Air Force fighter groups, whose average number of lost bombers was 46.

Moton Field

Indeed, for decades after World War II, the 332nd Fighter Group was reputed to be the only fighter group never to have lost an escorted bomber to enemy aircraft, but that claim was never true. The legend originated in a magazine and newspaper article that appeared in March 1945, after the group had flown for seven months without losing an escorted bomber. The group’s escorted bomber losses had been in the summer of 1944, and there were other such losses on a March 24, 1945, mission to Berlin, Germany. That mission was the longest Fifteenth Air Force bombing mission of the war. It was further notable because Tuskegee Airmen 1st Lieutenants Roscoe Brown and Earl Lane, and 2nd Lieutenant Charles V. Brantley each shot down a German Me-262 fighter jet on the mission, which was truly remarkable because the jets were much faster than the Airmen’s propeller-driven P-51 Mustangs. They were not the first American pilots to have shot down German jets, or even the only American pilots to shoot down German jets on that mission, as reported by some sources, but their heroism contributed to the 332nd Fighter Group’s earning its only Distinguished Unit Citation of the war for its part in the Berlin mission. For the group’s 99th Fighter Squadron, it was the third Distinguished Unit Citation.

Moton Field

Indeed, for decades after World War II, the 332nd Fighter Group was reputed to be the only fighter group never to have lost an escorted bomber to enemy aircraft, but that claim was never true. The legend originated in a magazine and newspaper article that appeared in March 1945, after the group had flown for seven months without losing an escorted bomber. The group’s escorted bomber losses had been in the summer of 1944, and there were other such losses on a March 24, 1945, mission to Berlin, Germany. That mission was the longest Fifteenth Air Force bombing mission of the war. It was further notable because Tuskegee Airmen 1st Lieutenants Roscoe Brown and Earl Lane, and 2nd Lieutenant Charles V. Brantley each shot down a German Me-262 fighter jet on the mission, which was truly remarkable because the jets were much faster than the Airmen’s propeller-driven P-51 Mustangs. They were not the first American pilots to have shot down German jets, or even the only American pilots to shoot down German jets on that mission, as reported by some sources, but their heroism contributed to the 332nd Fighter Group’s earning its only Distinguished Unit Citation of the war for its part in the Berlin mission. For the group’s 99th Fighter Squadron, it was the third Distinguished Unit Citation.

During its combat overseas, the 332nd Fighter Group and its four squadrons shot down a total of 112 enemy airplanes. Although no Tuskegee Airman shot down five or more aircraft to become an “ace,” four of the pilots shot down three enemy aircraft in one day, and three of the black pilots earned four aerial victory credits. Among them was Lee Archer, who was rumored to have been the only black ace. That claim, and the associated story that one of his aerial victory credits was reduced or taken away, is not historically accurate. The other Tuskegee Airmen with four aerial victory credits were Joseph Elsberry and Edward Toppins.

The 332nd Fighter Group completed its combat missions in late April 1945, and the war in Europe ended in early May. Its mission accomplished, the group redeployed to the United States and was inactivated in October. Even after serving in combat, the Airmen were segregated as they disembarked from the ship in which they returned to the United States.

Another Tuskegee Airmen organization that has received less attention than the 332nd Fighter Group is the 477th Bombardment Group and its four squadrons, the 616th, 617th, 618th, and 619th Bombardment Squadrons. The pilots of the 477th and its squadrons all trained at Tuskegee, but the group was never based there. In January 1944, it was activated as the first black bombardment group at Selfridge Field in Michigan, where it replaced the 332nd Fighter Group when the latter deployed overseas. The 477th Bombardment Group never deployed overseas and never entered combat. It was activated relatively late and was moved several times in the course of its preparation for combat. Its training took longer than that of a fighter group because in addition to pilots, its B-25s needed navigators and bombardiers who had to train in segregated classes at other bases.

Freeman Field Arrests, 1945

The 477th is best known for a “mutiny” at Freeman Field, Indiana, in April 1945. The white commander of the base attempted to establish separate officers’ clubs at Freeman Field, one ostensibly for trainers and one for trainees. Several members of the 477th suspected the real reason was racial segregation and attempted to enter the club reserved for whites. For their refusal to go along with the segregation policy at the base, 101 personnel of the 477th members were arrested. They were later exonerated because Army regulations at the time noted that any officer at a base was entitled to belong to the base’s officers’ club. The war ended before the unit could deploy to the Pacific for action against Japan. Colonel Davis returned to the United States to take over command of the 477th Bombardment Group from a white officer in response to the mutiny. For their resistance to racism, members of the 477th are remembered as pioneers for racial justice. The famous 99th Fighter Squadron was assigned to the group, and it was designated as the 477th Composite Group. Shortly thereafter, the group moved to Lockbourne Army Air Base in Ohio.

Freeman Field Arrests, 1945

The 477th is best known for a “mutiny” at Freeman Field, Indiana, in April 1945. The white commander of the base attempted to establish separate officers’ clubs at Freeman Field, one ostensibly for trainers and one for trainees. Several members of the 477th suspected the real reason was racial segregation and attempted to enter the club reserved for whites. For their refusal to go along with the segregation policy at the base, 101 personnel of the 477th members were arrested. They were later exonerated because Army regulations at the time noted that any officer at a base was entitled to belong to the base’s officers’ club. The war ended before the unit could deploy to the Pacific for action against Japan. Colonel Davis returned to the United States to take over command of the 477th Bombardment Group from a white officer in response to the mutiny. For their resistance to racism, members of the 477th are remembered as pioneers for racial justice. The famous 99th Fighter Squadron was assigned to the group, and it was designated as the 477th Composite Group. Shortly thereafter, the group moved to Lockbourne Army Air Base in Ohio.

Tuskegee Army Air Field ceased training black pilots in 1946, but the 477th remained as the only black flying group until it was replaced by the reactivated 332nd Fighter Group at Lockbourne in July 1947. In that year, the National Security Act became law, establishing the United States Air Force, and the 332nd Fighter Group was assigned to the new military service. The 332nd Fighter Group won the propeller-driven aircraft category at an Air Force-wide gunnery meet at Las Vegas in 1949; however, it was disbanded later that year, and members were assigned to formerly all-white organizations in the interest of racial integration.

Pres. Harry S. Truman had issued Executive Order 9981 in 1948, mandating the racial integration of all military services. Eventually there were black Navy and Marine Corps pilots as well as black Air Force pilots whose way was paved by the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II.

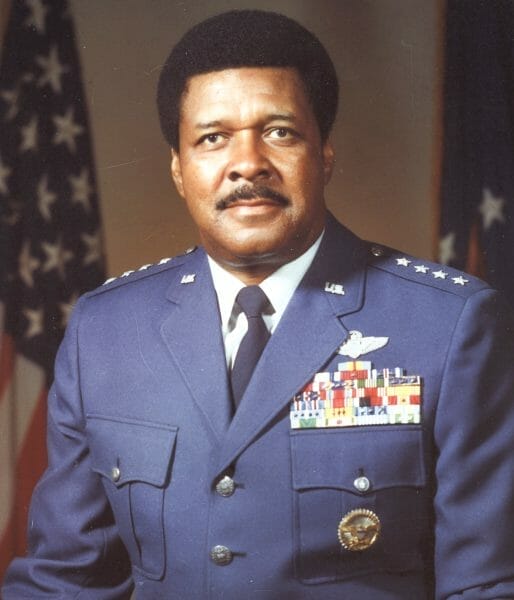

Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James

Many of the Tuskegee airmen remained in the Air Force after the 332nd Fighter Group inactivated. Davis became the first black general in the Air Force. Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James, after serving in the 477th Bombardment Group, flew fighter aircraft in the Korean and Vietnam wars and rose to become the first African American four-star general in the Air Force. Col. Charles McGee, who had served with the 332nd Fighter Group in World War II, also served in Korea and Vietnam and flew 409 combat missions, more than any other Air Force pilot in the three wars.

Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James

Many of the Tuskegee airmen remained in the Air Force after the 332nd Fighter Group inactivated. Davis became the first black general in the Air Force. Gen. Daniel “Chappie” James, after serving in the 477th Bombardment Group, flew fighter aircraft in the Korean and Vietnam wars and rose to become the first African American four-star general in the Air Force. Col. Charles McGee, who had served with the 332nd Fighter Group in World War II, also served in Korea and Vietnam and flew 409 combat missions, more than any other Air Force pilot in the three wars.

McGee and other Airmen formed Tuskegee Airmen Incorporated in the early 1970s as an association of veterans of Tuskegee Airmen organizations. The organization educates the public about the heritage of the Tuskegee Airmen and sponsors educational programs for youth, especially those interested in going into the field of aviation. It later included many members who were not original Tuskegee Airmen but who supported them and their programs.

Tuskegee Airman Roscoe Brown Jr. Medal Ceremony

In 2007, Pres. George W. Bush presented a Congressional Gold Medal collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen. At the March ceremony in the rotunda of the Capitol, he saluted many of the surviving Tuskegee Airmen who were able to attend, expressing the nation’s gratitude for all they had accomplished for a country in which they were once second-class citizens. The Tuskegee Airmen were not only military heroes, but also pioneers for racial justice, who, by serving honorably in the Korean and Vietnam wars, contributed to the continued integration of the military and the broader integration of American society. In 2012, Lucasfilm Ltd.released Red Tails, a feature film about the Tuskegee Airmen and their participation in bombing raids during 1944. In July 2023, a historical marker honoring the 332nd Fighter Group was unveiled in Nuovo Cliternia, a small town near where Ramitelli Airfield was located. In addition, a local library dedicated a room to the Airmen featuring information and photographs about the group.

Tuskegee Airman Roscoe Brown Jr. Medal Ceremony

In 2007, Pres. George W. Bush presented a Congressional Gold Medal collectively to the Tuskegee Airmen. At the March ceremony in the rotunda of the Capitol, he saluted many of the surviving Tuskegee Airmen who were able to attend, expressing the nation’s gratitude for all they had accomplished for a country in which they were once second-class citizens. The Tuskegee Airmen were not only military heroes, but also pioneers for racial justice, who, by serving honorably in the Korean and Vietnam wars, contributed to the continued integration of the military and the broader integration of American society. In 2012, Lucasfilm Ltd.released Red Tails, a feature film about the Tuskegee Airmen and their participation in bombing raids during 1944. In July 2023, a historical marker honoring the 332nd Fighter Group was unveiled in Nuovo Cliternia, a small town near where Ramitelli Airfield was located. In addition, a local library dedicated a room to the Airmen featuring information and photographs about the group.

Further Reading

- Caver, Joseph, Jerome Ennels, and Daniel Haulman. The Tuskegee Airmen: An Illustrated History, 1939-1949. Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 2011.

- Davis, Benjamin O. Jr. Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., American: An Autobiography. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991.

- Hardesty, Von. Black Wings: Courageous Stories of African Americans in Aviation and Space History. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.

- Haulman, Daniel. The Tuskegee Airmen Chronology: A Detailed Timeline of the Red Tails and Other Black Pilots of World War II. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2018.

- Jakeman, Robert J. The Divided Skies: Establishing Segregated Flight Training at Tuskegee, Alabama, 1934-1942. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992.