John Augustus Walker

John Augustus Walker (1901-1967) was a Mobile artist best known for the murals he painted for the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. He also painted portraits and landscapes and designed Mardi Gras floats and costumes. During his career, Walker received numerous local, state, and national awards for his work and was one of the most active artists of his time in the greater Mobile area.

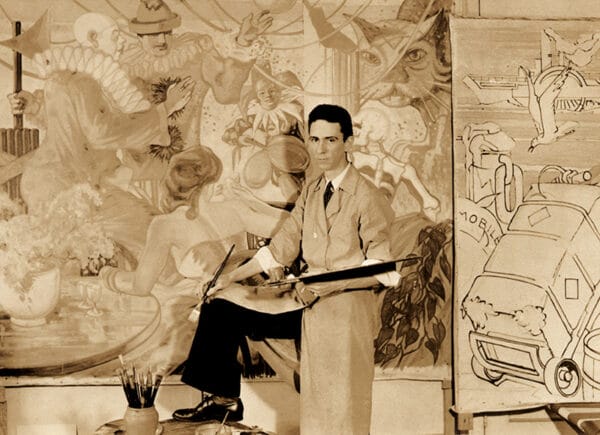

John Augustus Walker at Work

Born in Mobile, Mobile County, on February 9, 1901, to John L. Walker and Lilly Roche Walker, Walker was first encouraged to pursue art by teacher Maud Mayme Simpson during his years at elementary school in the Mobile County School System. At age 16, Walker entered the work force as a stenographer for real estate agent F. M. Backes to augment the income from his father’s business, the Alabama Tent and Awning Company. Gaining employment at the Mobile and Ohio (M&O) Railroad‘s Freight Department by 1920, young Walker worked daily 12-hour shifts from 1 p.m. to 1 a.m. During his off hours, he began a limited sleep regimen that allowed him more time to study drawing and painting. About this time, Walker also began studying under Mobile artist Edmund C. De Celle.

John Augustus Walker at Work

Born in Mobile, Mobile County, on February 9, 1901, to John L. Walker and Lilly Roche Walker, Walker was first encouraged to pursue art by teacher Maud Mayme Simpson during his years at elementary school in the Mobile County School System. At age 16, Walker entered the work force as a stenographer for real estate agent F. M. Backes to augment the income from his father’s business, the Alabama Tent and Awning Company. Gaining employment at the Mobile and Ohio (M&O) Railroad‘s Freight Department by 1920, young Walker worked daily 12-hour shifts from 1 p.m. to 1 a.m. During his off hours, he began a limited sleep regimen that allowed him more time to study drawing and painting. About this time, Walker also began studying under Mobile artist Edmund C. De Celle.

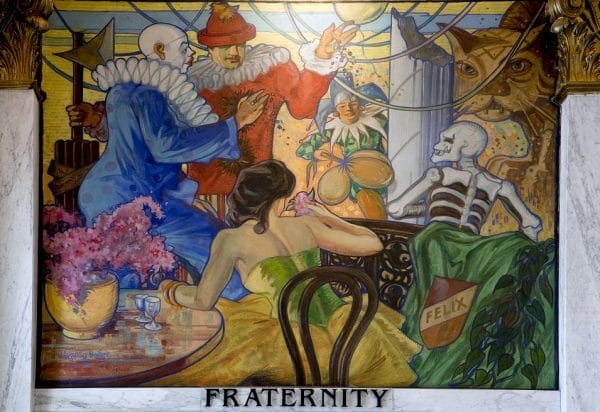

John Augustus Walker Mural

Around 1921, Walker received a company-ordered transfer to St. Louis, Missouri, where he continued to clerk at the M&O office and also enrolled at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, which was associated with Washington University’s School of Fine Arts. The faculty included Dutch sculptor Victor Holm, American Tonalist painter Edmund Wuerpel, and American Impressionist painter Frederick Greene Carpenter. Walker studied there for six years, and his use of detailed compositions and bright colors can be traced back to the influence of these men. Later trips to Key West, Florida, Cuba, and other destinations throughout the Gulf Coast region intensified Walker’s use of strong, bright colors. In 1925, Walker viewed a series of murals painted by Frank Brangwyn in the Missouri State Capitol and was influenced by his choice of subject matter and artistic style.

John Augustus Walker Mural

Around 1921, Walker received a company-ordered transfer to St. Louis, Missouri, where he continued to clerk at the M&O office and also enrolled at the St. Louis School of Fine Arts, which was associated with Washington University’s School of Fine Arts. The faculty included Dutch sculptor Victor Holm, American Tonalist painter Edmund Wuerpel, and American Impressionist painter Frederick Greene Carpenter. Walker studied there for six years, and his use of detailed compositions and bright colors can be traced back to the influence of these men. Later trips to Key West, Florida, Cuba, and other destinations throughout the Gulf Coast region intensified Walker’s use of strong, bright colors. In 1925, Walker viewed a series of murals painted by Frank Brangwyn in the Missouri State Capitol and was influenced by his choice of subject matter and artistic style.

In 1926, Walker participated in the 14th annual St. Louis Artists Guild exhibition highlighting works he produced as a student before spending the next few years visiting cities across the country to study directly from paintings housed in other museums. Having left the M&O Railroad, Walker returned to Mobile to pursue a career as a full-time artist, and his work was featured in a 1929 two-man exhibition. In 1933, he was featured in a well-received one-man show at the Woman’s Club in Mobile. Setting up a studio at 59½ North Royal Street, Walker pursued commissions for both commercial and public works of art, including stage designs, advertisements, billboards, and murals. In 1934, he completed a series of murals for Smith Bakery (now privately owned). In May 1935, Walker moved his studio to the second floor of 57½ North Royal Street. From that location, he designed floats for Mardi Gras mystic societies, such as the Infant Mystics (IM) and Knights of Revelry (KOR). As a charter member of the Allied Art Guild of Mobile, he served as one of its original instructors and actively supported the Alabama Art League of Montgomery.

Sketch for Transportation Mural

At the height of the Great Depression, artists across the United States were paid by the federal government to produce murals of American life in public buildings as a way to evoke the national spirit and combat the economic downturn that put nearly one-fourth of the population out of work. As with many artists during this time, Walker began producing murals, including several for the newly constructed Federal Building Courtroom and for the Birmingham Public Schools. He also received an invitation to participate in the New York Studio Guild’s national exhibition of artists. He was awarded WPA Project #2332-(1) in 1935, for which he produced some of his most recognized murals depicting the history of Mobile. They would adorn the lobby walls in Mobile’s Old City Hall/Southern Market complex (now the History Museum of Mobile) and feature such subjects as Mardi Gras, transportation, education, and slavery. Hampered by delays in payment from the WPA office in Montgomery, Walker fought to complete the murals, which he chose to produce in his preferred and costlier medium of oil paint. In all, he painted 11 canvases between September 29, 1935, and July 5, 1936, and installed them in right-to-left sequence on July 25 and 26. The murals represent the only WPA mural project awarded to the City of Mobile, with Walker receiving $145 for the work.

Sketch for Transportation Mural

At the height of the Great Depression, artists across the United States were paid by the federal government to produce murals of American life in public buildings as a way to evoke the national spirit and combat the economic downturn that put nearly one-fourth of the population out of work. As with many artists during this time, Walker began producing murals, including several for the newly constructed Federal Building Courtroom and for the Birmingham Public Schools. He also received an invitation to participate in the New York Studio Guild’s national exhibition of artists. He was awarded WPA Project #2332-(1) in 1935, for which he produced some of his most recognized murals depicting the history of Mobile. They would adorn the lobby walls in Mobile’s Old City Hall/Southern Market complex (now the History Museum of Mobile) and feature such subjects as Mardi Gras, transportation, education, and slavery. Hampered by delays in payment from the WPA office in Montgomery, Walker fought to complete the murals, which he chose to produce in his preferred and costlier medium of oil paint. In all, he painted 11 canvases between September 29, 1935, and July 5, 1936, and installed them in right-to-left sequence on July 25 and 26. The murals represent the only WPA mural project awarded to the City of Mobile, with Walker receiving $145 for the work.

Alabama State Fair Mural

In 1939, the WPA, in conjunction with the Alabama Extension Service (now the Alabama Cooperative Extension System), commissioned Walker to produce 29 murals for the Alabama State Fair depicting the state’s agricultural past and how it was evolving. Known as the “Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture,” the series was conceived as a temporary project that would serve as a backdrop to exhibits of produce and cash crops from the various counties participating in the fair. Working from this viewpoint, Walker and extension staff members decided to produce the murals in tempera watercolor paint rather than more durable oils. Around this time, Walker also began caring for his ailing father. These demands on Walker’s time, along with detailed suggestions regarding the paintings from U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) employees involved in the project, created unforeseen delays. With the project falling behind schedule, organizers reduced the contracted number to 20 murals and again reduced it to 10. The USDA also suggested simplified design schemes to facilitate their timely completion. Three weeks before the fair, a mentally and physically exhausted Walker raced to complete the project. One week before the fair opened, Walker travelled to Birmingham to install the recently finished works. In the week that followed, more than 300,000 people, including Gov. Frank Dixon, visited the fair and viewed the murals. The crowds represented the largest attendance of the fair in the state’s history. When the exhibition ended, the murals were shipped to Shreveport for the Louisiana State Fair and received a great deal of regional attention before being shipped back to Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) for storage.

Alabama State Fair Mural

In 1939, the WPA, in conjunction with the Alabama Extension Service (now the Alabama Cooperative Extension System), commissioned Walker to produce 29 murals for the Alabama State Fair depicting the state’s agricultural past and how it was evolving. Known as the “Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture,” the series was conceived as a temporary project that would serve as a backdrop to exhibits of produce and cash crops from the various counties participating in the fair. Working from this viewpoint, Walker and extension staff members decided to produce the murals in tempera watercolor paint rather than more durable oils. Around this time, Walker also began caring for his ailing father. These demands on Walker’s time, along with detailed suggestions regarding the paintings from U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) employees involved in the project, created unforeseen delays. With the project falling behind schedule, organizers reduced the contracted number to 20 murals and again reduced it to 10. The USDA also suggested simplified design schemes to facilitate their timely completion. Three weeks before the fair, a mentally and physically exhausted Walker raced to complete the project. One week before the fair opened, Walker travelled to Birmingham to install the recently finished works. In the week that followed, more than 300,000 people, including Gov. Frank Dixon, visited the fair and viewed the murals. The crowds represented the largest attendance of the fair in the state’s history. When the exhibition ended, the murals were shipped to Shreveport for the Louisiana State Fair and received a great deal of regional attention before being shipped back to Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) for storage.

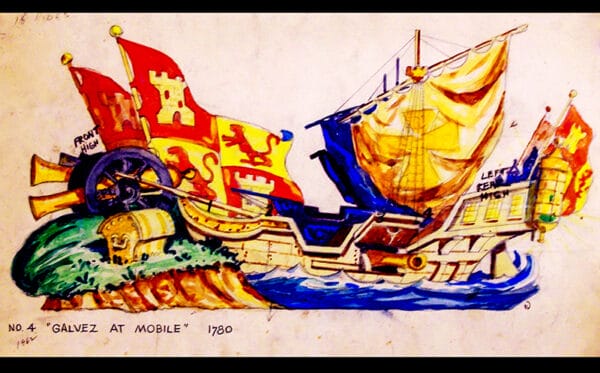

Mardi Gras Float Design

Walker continued producing small-scale commissions for individual buyers throughout his life. His later endeavors, however, never received as much acclaim as his WPA projects. Perhaps because of the outbreak of World War II and because of his decision to begin working as a clerk for the L&N Railroad, much of the time he once devoted to art projects was turned over to war-related work. On December 31, 1934, he married Lucy Roach, with whom he had one son. Walker died of pneumonia on June 22, 1967, and was buried in Pine Crest Cemetery in Mobile. After his father’s death, Walker’s son, J. A. Walker, donated many of his father’s family-held painted works, preliminary sketches, correspondences, and financial documents to the History Museum of Mobile. These items comprise the John Augustus Walker Collection, which is open to the public for research as an aid in the preservation of Walker’s legacy.

Mardi Gras Float Design

Walker continued producing small-scale commissions for individual buyers throughout his life. His later endeavors, however, never received as much acclaim as his WPA projects. Perhaps because of the outbreak of World War II and because of his decision to begin working as a clerk for the L&N Railroad, much of the time he once devoted to art projects was turned over to war-related work. On December 31, 1934, he married Lucy Roach, with whom he had one son. Walker died of pneumonia on June 22, 1967, and was buried in Pine Crest Cemetery in Mobile. After his father’s death, Walker’s son, J. A. Walker, donated many of his father’s family-held painted works, preliminary sketches, correspondences, and financial documents to the History Museum of Mobile. These items comprise the John Augustus Walker Collection, which is open to the public for research as an aid in the preservation of Walker’s legacy.

John Augustus Walker Self-portrait

In 1979, Hurricane Frederic severely damaged the Southern Market/Old City Hall Building in Mobile. Great efforts were taken to remove Walker’s murals from the lobby, preserve them, and install them again as they were originally placed in 1935. The high-profile restoration project, headed by Mobile architectural firm Holmes and Holmes, again thrust Walker’s works into the spotlight, and other forgotten works began to reappear. For example, Walker’s state fair murals resurfaced in 1985 and were conserved. Today, the murals are considered some of most valuable historic items owned by the Alabama Extension System. Because they are fragile, however, the pieces remain in the Special Collections of the Ralph Brown Draughon Library at Auburn University, where they are available to researchers and only periodically placed on public exhibition. Walker’s Southern Market murals still greet visitors to the History Museum of Mobile and remain a focal point in the study of the artist who created them.

John Augustus Walker Self-portrait

In 1979, Hurricane Frederic severely damaged the Southern Market/Old City Hall Building in Mobile. Great efforts were taken to remove Walker’s murals from the lobby, preserve them, and install them again as they were originally placed in 1935. The high-profile restoration project, headed by Mobile architectural firm Holmes and Holmes, again thrust Walker’s works into the spotlight, and other forgotten works began to reappear. For example, Walker’s state fair murals resurfaced in 1985 and were conserved. Today, the murals are considered some of most valuable historic items owned by the Alabama Extension System. Because they are fragile, however, the pieces remain in the Special Collections of the Ralph Brown Draughon Library at Auburn University, where they are available to researchers and only periodically placed on public exhibition. Walker’s Southern Market murals still greet visitors to the History Museum of Mobile and remain a focal point in the study of the artist who created them.

Further Reading

- Dupree, Bruce. “John Augustus Walker and the Historical Panorama of Alabama Agriculture.” Alabama Heritage 89 (Summer 2008): 33-39.

- Lawrence, Maggie. “Depression Era Paintings Capture History of Alabama Agriculture.” Ag Illustrated 3 (Summer 2006): 7.