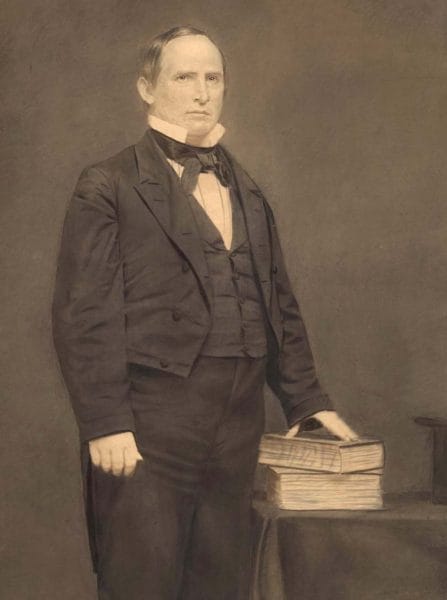

James Pugh

James Pugh

James Lawrence Pugh (1820-1907) served in the U.S. House of Representatives on the eve of the Civil War and in the U.S. Senate after the Reconstruction era. Pugh is remembered in Alabama history for staunchly defending the South and states’ rights and for serving in the Confederate Army and Confederate Congress while also being more willing to compromise during his service in the Senate. He was a self-made man who rose from poverty to become wealthy and influential.

James Pugh

James Lawrence Pugh (1820-1907) served in the U.S. House of Representatives on the eve of the Civil War and in the U.S. Senate after the Reconstruction era. Pugh is remembered in Alabama history for staunchly defending the South and states’ rights and for serving in the Confederate Army and Confederate Congress while also being more willing to compromise during his service in the Senate. He was a self-made man who rose from poverty to become wealthy and influential.

Pugh was born near Waynesboro, Georgia, officially on December 12, 1820, though some sources indicate that he was born on May 3 of that year. After the death of his mother, Anne Silvia (Tilman) Pugh in 1824, his father, Robert Pugh, moved the family (sources mention one brother) to Pike County, Alabama, in Creek Indian territory. Robert Pugh was reportedly killed in 1830 by Creek Indians, leaving Pugh penniless. He went to live with relatives in Barbour County and supported himself in his teen years by carrying mail and clerking in a dry goods store; he also studied law at this time. In 1836 he joined the Eufaula Rifles and fought against Creek Indians who were resisting removal in the Second Creek War; he resumed his study of law when hostilities ended. By 1841, he had been admitted to the Alabama bar and formed a partnership with Jefferson Buford in Eufaula. He would practice law there for nearly 40 years and also manage a plantation, farmed by a small number of enslaved people. Pugh was married in 1847 or 1848 to Sara Sarena Hunter of a prosperous Eufaula family. The couple would have nine children, three of whom died in infancy.

Pugh enjoyed antebellum politics, engaging in lengthy discussions on the great sectional issues of the day, favoring the South and states’ rights. As a Whig, he had been a member of the “Eufaula Regency,” a powerful group composed of disaffected Whigs and Democrats who espoused secession. It counted among its members William L. Yancey and future governor William Calvin Oates. In a spirited 1848 congressional campaign known as the “War of the Roses,” Pugh was narrowly defeated by a leading Alabama Whig, Henry W. Hilliard, whom Pugh claimed was not supportive enough of the South. The intensity of the campaign between the two hastened Pugh’s exit from the party, and in 1850, he switched to the Democrats, whom he found more sympathetic to his position on state sovereignty.

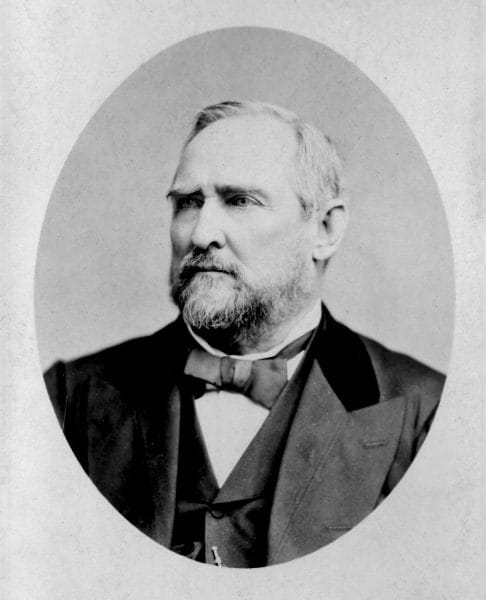

James Pugh

Pugh’s rise within Alabama’s Democratic Party hierarchy was quick. He was selected as an elector at large for Pres. James Buchanan in 1856 and used the position to build close personal ties and political support. By 1859, his political base was so secure that he easily defeated his opposition when he ran for Congress. He resigned his seat, however, following Alabama’s secession from the Union in January 1861 and returned to Alabama with other members of the delegation.

James Pugh

Pugh’s rise within Alabama’s Democratic Party hierarchy was quick. He was selected as an elector at large for Pres. James Buchanan in 1856 and used the position to build close personal ties and political support. By 1859, his political base was so secure that he easily defeated his opposition when he ran for Congress. He resigned his seat, however, following Alabama’s secession from the Union in January 1861 and returned to Alabama with other members of the delegation.

Pugh maintained a high profile in Montgomery that February when southern delegates gathered to form the new Confederate government. He and a small group met President-elect Jefferson Davis at the Union Railroad Station on the night of February 16 and escorted the statesman in a torchlight parade to the Exchange Hotel. Pugh rejoined the Eufaula Rifles and served one year in 1861 as a private in the First Alabama Infantry at Fort Barrancas near Pensacola, Florida. He was elected to the Confederate Congress in 1861 and again in 1863. After the war, he was president of the Democratic State Convention in 1874, a delegate to the constitutional convention in 1875, and a presidential elector for Samuel Tilden in 1876.

After the death of Sen. George S. Houston in 1879, Pugh was elected by the state legislature to complete the four years remaining in Houston’s term, beginning in 1880. In his acceptance speech to legislators, he reaffirmed his dedication to Democratic principles and pledged that in the Senate he would defend the South against the Republican Party; he was generally a trusted colleague of Sen. John Tyler Morgan. Pugh won reelection in 1884 and in 1890, defeating challenger Gov. Thomas Seay in the Democratic primary. During his terms, Pugh served on the Education and Labor Committee and as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the Fifty-third Congress. He reportedly became more sensitive to workers’ issues while a member of a special committee investigating the cause of labor strikes. Some the panel’s work led to the creation of the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

He fought for free coinage of silver, tariff reductions, restrictions of the privileges granted national banks, clearing the Tennessee River for navigation, and expanding the United States Merchant Marine. An intense party loyalist, he strongly defended Pres. Grover Cleveland against an effort in the Senate to inspect his private records. On one occasion, Cleveland offered Pugh a seat on the U.S. Supreme Court, but he declined because of his age. Interestingly, during his 16 years in the Senate, Pugh rarely spoke on the Senate floor, though a notable exception was a speech in favor of a bill increasing federal education funding to reduce illiteracy. The money would have been a boon to Alabama, where illiteracy was in excess of 30 percent among individuals 10 years or older, but the bill died in the House of Representatives. Pugh was, however, reportedly an aggressive questioner in committee hearings. In a three-way race in 1896 against Edmund W. Pettus, a noted attorney and former Confederate general, and Gov. Oates, Pugh suffered defeat in the Democratic primary. This loss embittered him, and he spent most of his remaining years in Washington, D.C., railing against many of the policies that he previously had endorsed. He died there on March 9, 1907; his body was returned to Eufaula, where he was buried in the Fairview Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama United States Senators by Elbert L. Watson (Huntsville, Ala: Strode Publishers, 1982).

Further Reading

- Davidson, Mary Jane. “James Lawrence Pugh: A Half Century in Politics.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1971.