Public Education in Antebellum Alabama

Education during Alabama’s antebellum era could best be described as haphazard, with a few notable exceptions. It easily exceeded the educational progress of the territorial period, but real progress remained centered in the state’s largest and most affluent city, Mobile.

Barton Academy

The city of Mobile was a leader in early public education efforts, establishing Barton Academy in 1836 with $50,000 in lottery proceeds. What would become the first real public school system in the state saw enrollment grow steadily through 1853, when it educated 854 students. In 1852, Mobile consolidated the schools’ funds and formed a larger public education system under a board of commissioners, with additional funding coming from fines, land grants, liquor taxes, and a percentage of tax revenue. In 1854, Barton Academy was divided into departments. The Primary School was tuition-free, and students remained at that level until they had mastered reading, spelling words, punctuation, counting to 100, and performing simple math problems. The Intermediate Division was also tuition-free and focused on elocution, writing, addition, multiplication, subtraction, and counting to 1,000. The Grammar School and High School charged tuition of $1.50 and $3.00 for a school year, respectively, and offered advanced instruction in spelling, penmanship, math, geography, English, algebra, and geometry.

Barton Academy

The city of Mobile was a leader in early public education efforts, establishing Barton Academy in 1836 with $50,000 in lottery proceeds. What would become the first real public school system in the state saw enrollment grow steadily through 1853, when it educated 854 students. In 1852, Mobile consolidated the schools’ funds and formed a larger public education system under a board of commissioners, with additional funding coming from fines, land grants, liquor taxes, and a percentage of tax revenue. In 1854, Barton Academy was divided into departments. The Primary School was tuition-free, and students remained at that level until they had mastered reading, spelling words, punctuation, counting to 100, and performing simple math problems. The Intermediate Division was also tuition-free and focused on elocution, writing, addition, multiplication, subtraction, and counting to 1,000. The Grammar School and High School charged tuition of $1.50 and $3.00 for a school year, respectively, and offered advanced instruction in spelling, penmanship, math, geography, English, algebra, and geometry.

Elsewhere during Alabama’s antebellum years, education was not a paramount concern for most individuals. Some planter families, particularly New Englanders who had migrated to the Black Belt considered education an important activity, but the vast majority of settlers in Alabama viewed education as a largely impractical exercise that contributed little to agricultural life and fostered snobbery and arrogance. Such frontier anti-intellectualism carried over into the modern South and continues to result in low public support for revenue measures for education.

McGuffey’s Reader

The structure of a common classroom varied from school to school, but all were crude at best. Schools were often located in buildings deemed unfit for other enterprises, lacked any indoor plumbing or sanitary services, and provided one common container for drinking water. A single individual might teach all grades, and at some schools, classes were ungraded and harsh discipline was the rule, with corporal punishment administered with paddles, or in extreme cases, the lash. When a school could afford textbooks, the most common volume used was the McGuffey Reader. School subjects included mathematics, reading, grammar, spelling, and geography. In terms of enrollment, in 1840, 753 students were enrolled in schools and academies in the state. By 1850, more than 1,100 public schools were educating in excess of 28,000 students. By 1860, 1,903 Alabama schools enrolled more than 61,750 students. In addition, until the 1850s, private academies were the major providers of education. Between 1820 and 1840, for example, 250 such academies were chartered. By 1860, Alabama educated 10,778 students in about the same number of private academies.

McGuffey’s Reader

The structure of a common classroom varied from school to school, but all were crude at best. Schools were often located in buildings deemed unfit for other enterprises, lacked any indoor plumbing or sanitary services, and provided one common container for drinking water. A single individual might teach all grades, and at some schools, classes were ungraded and harsh discipline was the rule, with corporal punishment administered with paddles, or in extreme cases, the lash. When a school could afford textbooks, the most common volume used was the McGuffey Reader. School subjects included mathematics, reading, grammar, spelling, and geography. In terms of enrollment, in 1840, 753 students were enrolled in schools and academies in the state. By 1850, more than 1,100 public schools were educating in excess of 28,000 students. By 1860, 1,903 Alabama schools enrolled more than 61,750 students. In addition, until the 1850s, private academies were the major providers of education. Between 1820 and 1840, for example, 250 such academies were chartered. By 1860, Alabama educated 10,778 students in about the same number of private academies.

With adequate land set aside for education, Alabama had the potential to establish a statewide publicly supported system similar to other progressive states. But for all its potential, education in Alabama suffered from what would be a familiar refrain of inadequate funding and lack of public enthusiasm. Sale of public lands dedicated to education often comprised the only funding for schools. In north Alabama, where land values were much lower than in the Black Belt, little revenue was gained from such land sales, and schools there suffered. In 1836, the federal government divided the surplus of national land sales among the states, and Alabama received $669,086.78, all of which was deposited in the state bank for the public school fund. Unfortunately, after the Panic of 1837 and the ensuing economic depression, the bank collapsed in 1843 and the education funds were lost. Even with limited funds, a few township schools existed in the state until the 1850s, primarily the result of an emerging social consciousness. To some residents, however, public education served as a symbol that one’s family could not afford private tutors and thus were not of the proper social class.

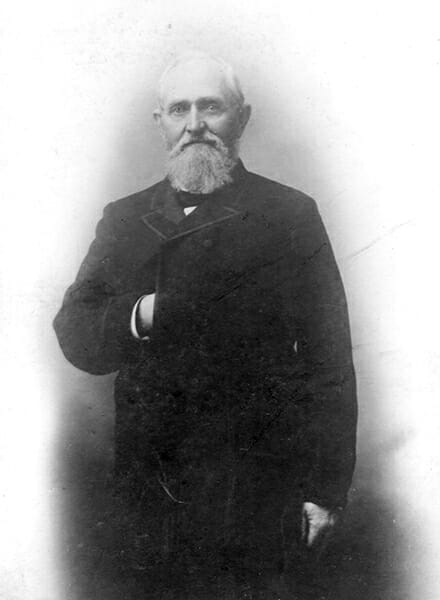

William F. Perry

The growth and success of the Mobile Public School System led to calls for reform in the way education was administered statewide. In 1854, the legislature passed the Public Education Act, some 35 years after the 1819 constitution promised that education “forever would be encouraged.” The law established a state superintendent of education to be elected by the legislature, with William F. Perry being given the position, and appropriated $100,000 annually for public education. After Perry took control of the state system, he introduced the McGuffey Reader and rudimentary topics such as U.S. history and geography. Additional money was expected from the sale of the one-sixteenth portion of townships and from additional taxes on insurance companies and railroads. The act also authorized each county to levy a 10-percent tax on real and personal property for schools.

William F. Perry

The growth and success of the Mobile Public School System led to calls for reform in the way education was administered statewide. In 1854, the legislature passed the Public Education Act, some 35 years after the 1819 constitution promised that education “forever would be encouraged.” The law established a state superintendent of education to be elected by the legislature, with William F. Perry being given the position, and appropriated $100,000 annually for public education. After Perry took control of the state system, he introduced the McGuffey Reader and rudimentary topics such as U.S. history and geography. Additional money was expected from the sale of the one-sixteenth portion of townships and from additional taxes on insurance companies and railroads. The act also authorized each county to levy a 10-percent tax on real and personal property for schools.

Despite the new school law, public education suffered from fiscal mismanagement, lack of public and legislative dedication, and annual uncertainty over funding. Tax revenues for school funding were so meager that most public schools depended on local support, including subscriptions and donations, to remain open. How long the doors remained open, however, depended largely upon the region in which a school resided and the local ability to supplement school funding. In more affluent areas of the state, schools had the resources to remain open longer, some for up to nine months. In poorer areas, schools might stay open for only five months. Even these meager gains would be set back with the outbreak of the Civil War, and the Reconstruction era would bring drastic change to the system as well.

Additional Resources

Griffith, Lucille. Alabama: A Documentary History to 1900. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968.

Lindsey, Tullye Borden, and James Armour Lindsay. “Some Light Upon Ante-Bellum Alabama Schools,” Peabody Journal of Education, 20 (July 1942): 37-41.