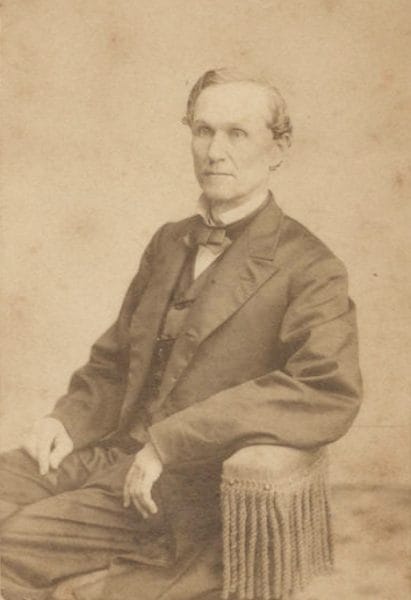

Thomas Hill Watts (1863-65)

Thomas Hill Watts (1819-1892) was Alabama’s eighteenth governor. His career in Alabama politics and government spanned the most critical period in southern and U.S. history. Beginning with the so-called Compromise of 1850, Watts figured prominently in the secession movement, the establishment of the Confederate government, and the white revolt against Congressional Reconstruction.

Thomas Hill Watts

Watts was born in the Alabama Territory on January 3, 1819, to John Hughes Watts, a prominent plantation owner, and Prudence Hill Watts and grew up in Butler County. He attended the University of Virginia, from which he graduated with honors in 1840. He then returned to Greenville, Butler County, and began practicing law. A year later, in 1842, he ran for the state house of representatives as a Whig. Watts won the election and represented Butler County through 1845. In 1848, he relocated his law practice to Montgomery. Records indicate that he greatly increased his property in land and enslaved people over the next decade, and thus his practice must have done well. Watts was married twice, to Elizabeth Brown Allen and Ellen C. Noyes.

Thomas Hill Watts

Watts was born in the Alabama Territory on January 3, 1819, to John Hughes Watts, a prominent plantation owner, and Prudence Hill Watts and grew up in Butler County. He attended the University of Virginia, from which he graduated with honors in 1840. He then returned to Greenville, Butler County, and began practicing law. A year later, in 1842, he ran for the state house of representatives as a Whig. Watts won the election and represented Butler County through 1845. In 1848, he relocated his law practice to Montgomery. Records indicate that he greatly increased his property in land and enslaved people over the next decade, and thus his practice must have done well. Watts was married twice, to Elizabeth Brown Allen and Ellen C. Noyes.

Watts differed little from mainstream Alabama Whigs on sectional issues during the early 1850s. He defended the so-called Compromise of 1850 as a definitive solution to the problem of slavery in the territories acquired from Mexico. Like many slaveowners in Alabama and the South, Watts feared that continued agitation over slavery would ultimately lead to the destruction of the Union and the abolition of slavery. Although Whigs briefly benefited from their support for the legislation, the state party found it difficult to respond to a reunited Democratic Party. By 1855, Alabama’s Whig party virtually disappeared, as did the national Whig party. Watts joined other Whigs in the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic Know-Nothing Party. He ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. House of Representatives as a Know Nothing in 1855. Watts exploited southern rights issues, demanding, for example, the right of slave-owners to take enslaved people to the Kansas territory, but lost the election. Impressed with the strength of the southern rights platform, Watts assumed a moderate southern rights posture between 1855 and 1860, supporting Constitutional Unionist John Bell in the national election of 1860. He joined other moderates in Alabama in supporting the possibility of secession if Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860.

As a delegate to the Alabama secession convention, Watts supported the view that all the southern states should agree to secede together. This cooperationist position was more moderate in comparison with that of delegates who argued that states should decide on their own whether or not to secede immediately. When the convention adopted an ordinance of secession, however, Watts joined the majority. When the war came, he raised a regiment and served briefly as a colonel in the Confederate Army.

John Gill Shorter

In politics, Watts maintained a relatively moderate course. He opposed John Gill Shorter, who favored immediate secession, in the Alabama gubernatorial election of 1861. Watts’s opposition to Shorter and his failed campaign for the Confederate Senate fostered suspicions in the state about his commitment to the southern cause. Confederate president Jefferson Davis, however, trusted Watts enough to appoint him attorney general of the Confederacy in 1862. During his brief tenure in this office, Watts played a leading role in the creation of the Confederate Supreme Court. He also facilitated the centralization of the Confederate government with his constitutional interpretations. For example, he upheld the constitutionality of the controversial Conscription Act of 1862, which allowed the Confederate government to press white men between the ages of 18 and 35 into military service.

John Gill Shorter

In politics, Watts maintained a relatively moderate course. He opposed John Gill Shorter, who favored immediate secession, in the Alabama gubernatorial election of 1861. Watts’s opposition to Shorter and his failed campaign for the Confederate Senate fostered suspicions in the state about his commitment to the southern cause. Confederate president Jefferson Davis, however, trusted Watts enough to appoint him attorney general of the Confederacy in 1862. During his brief tenure in this office, Watts played a leading role in the creation of the Confederate Supreme Court. He also facilitated the centralization of the Confederate government with his constitutional interpretations. For example, he upheld the constitutionality of the controversial Conscription Act of 1862, which allowed the Confederate government to press white men between the ages of 18 and 35 into military service.

Watts resigned from office in 1863 to return to Alabama and run for governor. His opponent, again, was John Gill Shorter. Ironically, given his expansionist view of centralized power in the Confederacy, Watts benefited from discontent among the electorate over Shorter’s impositions of state government authority. Watts also received support from the Peace Party, whose members in the state sought a quick end to the war.

Watts was victorious in this campaign and once in office soon dispelled any doubts about his commitment to the Confederate cause. He assured Alabamians that the war had his full support and struggled with the Peace Party until the end of the war. The opposition to Watts in the legislature severely limited his freedom to provide for the defense of Mobile and to address the deteriorating economic and social conditions in the state. For example, the legislature forced Watts into suspending the collection of state taxes in the mountain counties of north Alabama to relieve struggling farmers. Although tax relief satisfied some of Watts’s most vocal opponents, the loss in revenue meant that state aid for the indigent and other relief programs could not be adequately funded.

Watts also failed to secure cooperation from the legislature as he tried to deal with increasing lawlessness across the state. By 1864, Confederate deserters roamed the countryside plundering farms and attacking targets of opportunity, and Unionists engaged in battles with secessionists. Watts urgently requested an increase in the state militia so he could use it to restore order and defend Mobile, but the legislature refused to act. Watts did issue a proclamation ordering all foreign-born non-citizens to enlist in the state militia in hopes of building a force capable of providing internal security. Immigrants, however, largely refused to comply.

Relations with the Confederate government proved as frustrating for Watts as the legislature. Upon assuming office, he attempted to end corruption in the collection of food for the army, a Confederate government policy known as impressment. By 1864, impressment officers, along with some Confederate soldiers, were confiscating goods from farmers and selling them for profit. In addition, men posing as impressment agents were purchasing produce from farmers with counterfeit certificates. Watts recognized the demoralizing effect of this corruption and pleaded with the Confederate government to clean up the program. The national government, in the midst of a desperate fight for its very existence, could offer little help.

At the end of the war, federal troops arrested Watts near Union Springs in Bullock County and briefly imprisoned him. By the time he returned to his home, U.S forces had burned his entire cotton crop, and he later sold much of his land to pay debts. Driven by resentment against federal reconstruction policies, Watts became a Democrat and a leader in the Democratic Party’s successful campaign against Congressional Reconstruction. For the remainder of his life, Watts lived in Montgomery, where he practiced law. He died on September 16, 1892, and was buried in Montgomery’s Oakwood Cemetery.

Additional Resources

Fleming, Walter Lynwood. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. New York: Columbia University Press, 1905.

McMillan, Malcolm C. The Disintegration of a Confederate State: Three Governors Alabama’s Wartime Home Front, 1861-1865. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1986.