Oil and Gas Industry in Alabama

Mobile Bay Gas Platforms

Alabama is among the top 17 producers of oil and among the top 16 producers of natural gas in the United States. Oil and gas are found in many counties as well as in Mobile Bay. The state has developed some of the most stringent environmental regulations regarding drilling in its offshore waters. Alabama’s oil production has steadily increased from an average of just over five million barrels in 2009 to nine million barrels in 2015. Alabama’s natural gas production has steadily declined since 2005 but has leveled since 2012 at about 200 billion cubic feet per year. In 2015, the state the oil and gas industry contributed $11.3 billion to the Alabama economy, which was 6.4% of the state’s GDP.

Mobile Bay Gas Platforms

Alabama is among the top 17 producers of oil and among the top 16 producers of natural gas in the United States. Oil and gas are found in many counties as well as in Mobile Bay. The state has developed some of the most stringent environmental regulations regarding drilling in its offshore waters. Alabama’s oil production has steadily increased from an average of just over five million barrels in 2009 to nine million barrels in 2015. Alabama’s natural gas production has steadily declined since 2005 but has leveled since 2012 at about 200 billion cubic feet per year. In 2015, the state the oil and gas industry contributed $11.3 billion to the Alabama economy, which was 6.4% of the state’s GDP.

Geology of Oil and Natural Gas

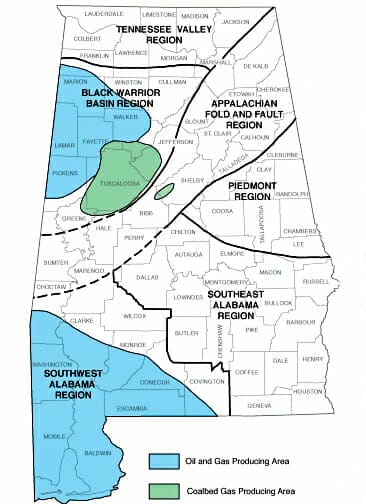

Alabama Oil and Gas Regions

Oil in Alabama generally occurs in the state’s two sedimentary basins, the Interior Salt Basin in the southwest and the Black Warrior Basin in the northwest, both of which extend westward into Mississippi. Geologists use the term “basin” to describe a broad area where layered sedimentary rocks sag thousands of feet downward into a “bowl” shape, although there is often no evidence of this at the surface. The Interior Salt Basin consists of Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks, which date back 200 million years. The Black Warrior Basin is composed of Paleozoic rocks, some of which date back 580 million years. This region is also famous for its vast coal reserves, such as the Warrior Coal Field.

Alabama Oil and Gas Regions

Oil in Alabama generally occurs in the state’s two sedimentary basins, the Interior Salt Basin in the southwest and the Black Warrior Basin in the northwest, both of which extend westward into Mississippi. Geologists use the term “basin” to describe a broad area where layered sedimentary rocks sag thousands of feet downward into a “bowl” shape, although there is often no evidence of this at the surface. The Interior Salt Basin consists of Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks, which date back 200 million years. The Black Warrior Basin is composed of Paleozoic rocks, some of which date back 580 million years. This region is also famous for its vast coal reserves, such as the Warrior Coal Field.

Despite the popular belief that oil comes from dinosaurs, in reality it originates from the decaying remains of countless microscopic creatures that died, fell to the ocean floor, and became buried under thousands of feet of sediment. The heat and pressure of the overlying sediments changed the chemical make-up of the organisms into crude oil. Natural gas, which is composed mainly of methane, is a by-product of this slow process and is found both with oil or by itself. Crude oil and natural gas are together referred to as petroleum.

Oil Rig

Petroleum forms in the microscopic pores of rocks such as sandstone and limestone and slowly makes its way to the surface. When the petroleum becomes trapped in its migration, it forms an oil or gas field. Common traps are geologic features known as faults and anticlines. Faults are cracks in layers of rock in which the rocks on either side of the crack move in relation to each other. This can be envisioned by thinking of a knife slicing through a layer cake and seeing one side of the cake slump downward. Anticlines are dome-shaped folds in sections of layered rock. Geologists search for these traps with machines that measure gravity, magnetic, and seismic data, all of which tell them critical properties of buried rock layers. Geologists refer to a likely place for oil or gas as a “prospect.” When a prospect is identified, “landmen” are sent in to lease the mineral rights from property owners, who retain a royalty, which is a share of the revenue generated by the oil and gas produced from the owner’s property. After the leases are acquired, drilling rigs are brought in to drill and test the prospect.

Oil Rig

Petroleum forms in the microscopic pores of rocks such as sandstone and limestone and slowly makes its way to the surface. When the petroleum becomes trapped in its migration, it forms an oil or gas field. Common traps are geologic features known as faults and anticlines. Faults are cracks in layers of rock in which the rocks on either side of the crack move in relation to each other. This can be envisioned by thinking of a knife slicing through a layer cake and seeing one side of the cake slump downward. Anticlines are dome-shaped folds in sections of layered rock. Geologists search for these traps with machines that measure gravity, magnetic, and seismic data, all of which tell them critical properties of buried rock layers. Geologists refer to a likely place for oil or gas as a “prospect.” When a prospect is identified, “landmen” are sent in to lease the mineral rights from property owners, who retain a royalty, which is a share of the revenue generated by the oil and gas produced from the owner’s property. After the leases are acquired, drilling rigs are brought in to drill and test the prospect.

Another type of oil resource occurs when oil makes its way to the surface forming a geologic feature known as tar sands. The Hartselle Sandstone in northwest Alabama is a prime example of such a surface oil field. Although geologists believe Alabama’s tar sands have future commercial use, most of the state’s known petroleum reserves are located underground.

Discovery of Oil and Gas Reserves

The world’s first oil discovery occurred in Pennsylvania in 1859. Chemists found they could refine the crude oil into certain components that were useful. The first of these refined products to find widespread use was kerosene, which quickly replaced whale oil as lamp fuel. Later, gasoline and other fuels were refined to power the engines of the fuel-thirsty twentieth century. By the end of World War II, the rapid demand for refined products meant that the hunt for oil spread quickly across the United States and the world.

Traces of petroleum, in the form of natural gas, were first discovered in Alabama in Morgan and Blount Counties in the late 1880s, and by 1902, natural gas was being supplied to the cities of Huntsville and Hazel Green. In 1909, a small discovery by Eureka Oil and Gas at Fayette fueled that city’s streetlights for a time, but no natural gas was recovered anywhere in the state for several decades afterward.

In 1945, the state legislature created the Alabama Oil and Gas Board (AOGB) to regulate the oil and gas industry in the state. When a discovery is made, the oil companies are required to take their information before the AOGB at a public hearing. The AOGB then issues special rules concerning the regulation and production of the petroleum; assures the rights of mineral owners; and ensures that environmental protection laws and regulations are followed. With the creation of the AOGB, the legislature appointed Walter B. Jones, Alabama’s third state geologist, as its supervisor.

Chesley Pruet and Dudley Hughes

Knowing the geology of the state extremely well, Jones became convinced that Alabama would one day become a significant petroleum producer. He continued to lobby the legislature for laws to encourage oil men to come to Alabama with their drilling rigs. But it was not until World War II broke out in 1939 that Jones saw his wishes come true, when demand for oil rose and Alabama’s fortunes changed. In 1944, Texas oilman Haroldson “H. L.” Hunt drilled beside a fault in Choctaw County and discovered the Gilbertown Field in the Eutaw Sand at a depth of 3,700 feet. That field produced 15 million barrels of oil (1 barrel = 42 gallons), not a lot by modern standards but enough to make “oil fever” spread rapidly. Other companies, many of which were run by independent prospectors popularly known as “wildcatters,” followed Hunt’s lead, but 11 years passed before they found the next significant discovery.

Chesley Pruet and Dudley Hughes

Knowing the geology of the state extremely well, Jones became convinced that Alabama would one day become a significant petroleum producer. He continued to lobby the legislature for laws to encourage oil men to come to Alabama with their drilling rigs. But it was not until World War II broke out in 1939 that Jones saw his wishes come true, when demand for oil rose and Alabama’s fortunes changed. In 1944, Texas oilman Haroldson “H. L.” Hunt drilled beside a fault in Choctaw County and discovered the Gilbertown Field in the Eutaw Sand at a depth of 3,700 feet. That field produced 15 million barrels of oil (1 barrel = 42 gallons), not a lot by modern standards but enough to make “oil fever” spread rapidly. Other companies, many of which were run by independent prospectors popularly known as “wildcatters,” followed Hunt’s lead, but 11 years passed before they found the next significant discovery.

In 1955 at Citronelle in Mobile County geologist Everett Eaves and legendary wildcatter Chesley Pruet established the most famous oil well in the state’s history, the No. 1 Donovan, discovering the biggest oil field east of the Mississippi River at the time. Citronelle produced 160 million barrels of oil from the Rodessa Sandstone, 12,000 feet down, becoming Alabama’s only “giant” oil field, which is a field that produces more than 100 million barrels. Expanding to 500 wells, Citronelle sparked a drilling flurry in south Alabama, but the results were mostly disappointing until the mid 1960s, when explorers made a series of discoveries in Jurassic rocks, from 12,000 to 20,000 feet below the surface. These discoveries, spearheaded by Pruet and his partner, geologist Dudley Hughes, added hundreds of millions of additional barrels of oil to Alabama’s discoveries.

Early Jurassic Landscape Reconstruction

As oil drilling boomed in south Alabama in the late 1960s and 1970s, wildcatter Walter Sistrunk struck gas in the Black Warrior Basin in Lamar County, as did engineer William Tucker in Fayette County. Both men, as well as Pruet and Hughes, headed small but aggressive companies called “Independents” that used investment money from various other oil industry sources. These pioneers lured many more companies, which spread natural gas development through the northwest Alabama region.

Early Jurassic Landscape Reconstruction

As oil drilling boomed in south Alabama in the late 1960s and 1970s, wildcatter Walter Sistrunk struck gas in the Black Warrior Basin in Lamar County, as did engineer William Tucker in Fayette County. Both men, as well as Pruet and Hughes, headed small but aggressive companies called “Independents” that used investment money from various other oil industry sources. These pioneers lured many more companies, which spread natural gas development through the northwest Alabama region.

During the post-war years, the oil industry in Alabama followed national trends, going through many cycles of ups and downs, depending on the price of oil. When foreign oil began to flow in vast amounts into the nation in the late 1950s and 1960s, oil prices fell and drilling slowed. In 1973, however, the Arab Oil Embargo sent prices soaring, and exploration picked up again. Many new oil and gas fields were discovered, among them the huge finds in Mobile County at Hatters Pond by Getty Oil Company, at Chunchula by Union Oil, and other big finds in Escambia County.

In the late 1980s, Alabama moved into the world spotlight as a consortium of companies, in concert with the federal government and the University of Alabama, began producing methane gas from coal beds in the Black Warrior Basin. Within a few years, gas companies sank thousands of shallow wells across west Alabama, adding two trillion cubic feet of gas to the state’s reserves. Other states and foreign countries closely watched the coal-bed methane technology develop in Alabama and applied it throughout the world.

Oil and Gas Prospecting and the Environment

Gas Rig in the Gulf of Mexico

In addition to its production capacity, Alabama also became a world leader in another oil-related technology: environmental protection. This development occurred simultaneously with what is considered by some to be Alabama’s most significant petroleum event. In 1968, at a time of elevated environmental awareness across the nation after a destructive offshore spill in California, Mobil Oil, Inc. began studying the petroleum potential of the deep Jurassic rocks under Mobile Bay. But the company met with stiff opposition from environmental groups, and its permit to drill was delayed for many years. After numerous meetings and debates involving Mobil, opposition groups, and state regulators, the permit was finally approved but with the strictest environmental oversight ever enacted in the industry.

Gas Rig in the Gulf of Mexico

In addition to its production capacity, Alabama also became a world leader in another oil-related technology: environmental protection. This development occurred simultaneously with what is considered by some to be Alabama’s most significant petroleum event. In 1968, at a time of elevated environmental awareness across the nation after a destructive offshore spill in California, Mobil Oil, Inc. began studying the petroleum potential of the deep Jurassic rocks under Mobile Bay. But the company met with stiff opposition from environmental groups, and its permit to drill was delayed for many years. After numerous meetings and debates involving Mobil, opposition groups, and state regulators, the permit was finally approved but with the strictest environmental oversight ever enacted in the industry.

In 1978, with protections in place to preserve the bay’s ecology, Mobil moved in a huge offshore rig. They drilled more than 21,000 feet into an ancient desert called the Norphlet Sandstone and discovered the largest natural gas field east of the Mississippi, the Lower Mobile Bay–Mary Ann Field. The discovery formed the core of offshore development that eventually located six trillion cubic feet of reserves and as of 2007 has sent $2.1 billion worth of royalties to Alabama’s Heritage Trust Fund, which uses the interest from the funds to help pay for the state’s education and infrastructure needs. The fund was the first of its kind in U.S. history. Oil and gas activity in Mobile Bay and the nearby Gulf of Mexico waters stands today as a global environmental standard for offshore drilling and production operations.

Current Oil and Gas Production in Alabama

Choctaw Ridge Oil Field

Walter B. Jones’s vision for Alabama has come true. Alabama now ranks 10th among the states in natural gas production and 15th in liquid petroleum. Since the first meager gas discovery at Hazel Green, thousands of wells have been drilled across the state. Most have produced nothing, but by 2007 the successful ones were producing nearly $2.5 billion worth of oil and gas annually, $500 million of which goes to Alabama’s citizens in the form of taxes, royalties, and trusts. Alabama’s several locally owned and operated companies join many others from across the nation and abroad to employ thousands of local workers in finding, extracting, refining, and transporting the state’s petroleum resources.

Choctaw Ridge Oil Field

Walter B. Jones’s vision for Alabama has come true. Alabama now ranks 10th among the states in natural gas production and 15th in liquid petroleum. Since the first meager gas discovery at Hazel Green, thousands of wells have been drilled across the state. Most have produced nothing, but by 2007 the successful ones were producing nearly $2.5 billion worth of oil and gas annually, $500 million of which goes to Alabama’s citizens in the form of taxes, royalties, and trusts. Alabama’s several locally owned and operated companies join many others from across the nation and abroad to employ thousands of local workers in finding, extracting, refining, and transporting the state’s petroleum resources.

Oil and gas is still being found in Alabama, and geologists believe new opportunities exist in the hard shales of the deep Black Warrior Basin beneath Pickens and Tuscaloosa Counties and in the thick fractured shales of St. Clair and neighboring counties.

Further Reading

- Cockrell, Alan. Drilling Ahead: The Quest for Oil in the Deep South, 1945-2005. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

- Hughes, Dudley J. Oil in the Deep South: A History of the Oil Business in Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, 1859-1945. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi, 1993.