Virginia Foster Durr

Over the course of her long life, Virginia Foster Durr (1903-1999) was a constant presence in Alabama politics and the movement for civil rights. Her life spanned most of the twentieth century, and Virginia Durr had a front-row seat for the New Deal, McCarthyism, and the civil rights movement. She spent years working to abolish the poll tax and to end segregation, and her husband, Clifford, an attorney, was involved with a number of civil rights cases.

Virginia Foster Durr

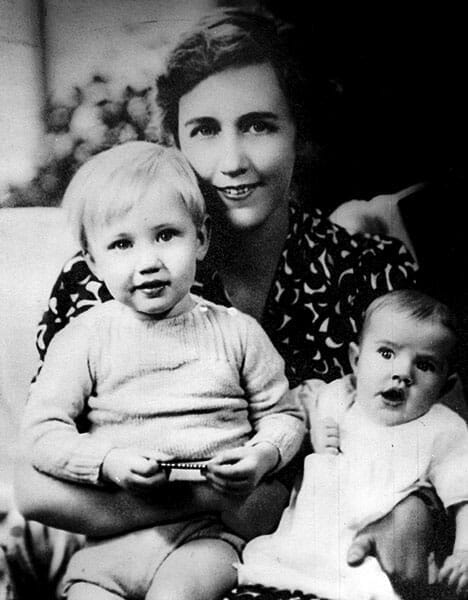

Virginia was born on August 6, 1903, in Birmingham, Jefferson County, to the family of Sterling Foster, a prominent Presbyterian minister, and Anne Patterson Foster. Her upbringing was steeped in traditional white southern mores, including acceptance of racial segregation, and she was taught to behave as a “southern lady.” Although her family was not wealthy, Virginia was sent to finishing school in New York, where she followed a rigorous academic program and was trained in the social graces. As a sophomore at Wellesley College, Durr came to question segregation after her experience in the college’s dining hall with “rotating tables,” the school’s policy of requiring students to eat meals with random groups of students, including African Americans. Durr initially protested this policy but was told that she could either accept it or leave the college; she chose to accept it.

Virginia Foster Durr

Virginia was born on August 6, 1903, in Birmingham, Jefferson County, to the family of Sterling Foster, a prominent Presbyterian minister, and Anne Patterson Foster. Her upbringing was steeped in traditional white southern mores, including acceptance of racial segregation, and she was taught to behave as a “southern lady.” Although her family was not wealthy, Virginia was sent to finishing school in New York, where she followed a rigorous academic program and was trained in the social graces. As a sophomore at Wellesley College, Durr came to question segregation after her experience in the college’s dining hall with “rotating tables,” the school’s policy of requiring students to eat meals with random groups of students, including African Americans. Durr initially protested this policy but was told that she could either accept it or leave the college; she chose to accept it.

Because of financial difficulties, Durr was forced to leave college during her junior year and return to Birmingham, where she met attorney Clifford Durr at church. Virginia had already rejected several suitors, and her family had begun to worry that she would never marry. After a brief courtship, she and Clifford married in April 1926. In 1933, the Durrs moved to Washington, D.C., after her husband accepted a position with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, an agency founded by the Hoover administration to try to shore up the economy in the early years of the Great Depression. He was later appointed to the Federal Communications Commission by Franklin Roosevelt. It was during their time in Washington and through her husband’s New Deal contacts that Virginia Durr’s activism began. She joined the Woman’s National Democratic Club and began a long involvement in the campaign to abolish the poll tax, which effectively denied most southern African Americans and poor whites the right to vote.

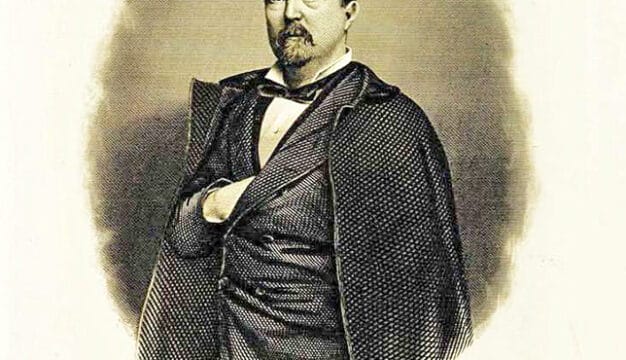

Clifford and Virginia Durr

In 1938, while still living in Washington, Durr became one of the founding members of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. Formed in part as a response to Franklin Roosevelt’s proclamation that the South was the leading economic problem in the nation, the SCHW was a biracial coalition formed in Birmingham in 1938 to challenge racial segregation and improve living and working conditions in the South. It was as democratic an organization as could be found in the South of the 1930s, drawing support from professors and journalists as well as mine workers and sharecroppers. The organization was spearheaded by a wide array of southern liberals, including Lillian Smith, Jim Dombrowski of the Highlander Folk School, and Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, who was also Durr’s brother-in-law. Eleanor Roosevelt was also present for the inaugural meeting in Birmingham, where she caused a minor controversy by refusing to sit in segregated seating. Durr was drawn to the SCHW primarily because of her interest in ending the poll tax, but she was also attracted to the group’s work with labor unions and its stance on civil rights. In 1941, Durr became vice president of the SCHW’s civil rights subcommittee, along with Texas representative Maury Maverick, who served as president. Although the SCHW was continually criticized by the conservative press because of its civil rights work and its alleged Communist ties, Durr later recalled her work with the organization as one of the happiest events of her life.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

In 1938, while still living in Washington, Durr became one of the founding members of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. Formed in part as a response to Franklin Roosevelt’s proclamation that the South was the leading economic problem in the nation, the SCHW was a biracial coalition formed in Birmingham in 1938 to challenge racial segregation and improve living and working conditions in the South. It was as democratic an organization as could be found in the South of the 1930s, drawing support from professors and journalists as well as mine workers and sharecroppers. The organization was spearheaded by a wide array of southern liberals, including Lillian Smith, Jim Dombrowski of the Highlander Folk School, and Supreme Court justice Hugo Black, who was also Durr’s brother-in-law. Eleanor Roosevelt was also present for the inaugural meeting in Birmingham, where she caused a minor controversy by refusing to sit in segregated seating. Durr was drawn to the SCHW primarily because of her interest in ending the poll tax, but she was also attracted to the group’s work with labor unions and its stance on civil rights. In 1941, Durr became vice president of the SCHW’s civil rights subcommittee, along with Texas representative Maury Maverick, who served as president. Although the SCHW was continually criticized by the conservative press because of its civil rights work and its alleged Communist ties, Durr later recalled her work with the organization as one of the happiest events of her life.

In 1941, the SCHW’s civil rights committee became the National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax, with Durr as its vice-chair. Like the SCHW, the NCAPT was continually attacked for its reputed Communist associations. The organization did, on occasion, receive financial support from various Communist-backed organizations, and Joseph Gelders, a Birmingham native and public Communist, was very active in both groups. As a whole, however, the red-baiting tactics of the group’s critics appear to be largely unfounded. The NCAPT accepted support from anyone who opposed the poll tax and made no distinctions based on political affiliations. Nevertheless, the Durrs would continue to be plagued by rumors that she was a Communist.

Because the Durrs did not publicly denounce Communism or join in the fierce red-baiting of the postwar years, they were often targeted by anti-Communist activists. In 1954, Durr was called to New Orleans to testify before Senator James Eastland’s Internal Security Committee, an agency similar to the House Un-American Activities Committee in its objective of investigating alleged Communists. The hearings in New Orleans came on the eve of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling, which was expected to strike down segregation in public education. Scholars have suggested that Durr was targeted because Eastland wanted to strike back at Hugo Black, who had joined in the unanimous Supreme Court decision in favor of Brown. She was brought before the committee ostensibly because of her work with the Southern Educational Fund, an allegedly “subversive” organization. Durr gave her name, stated that she was not a Communist, and then refused to answer further questions, standing in silent defiance of the committee as she was questioned, occasionally taking out a compact and powdering her nose. The stress of the hearings caused Clifford Durr to suffer a nervous collapse.

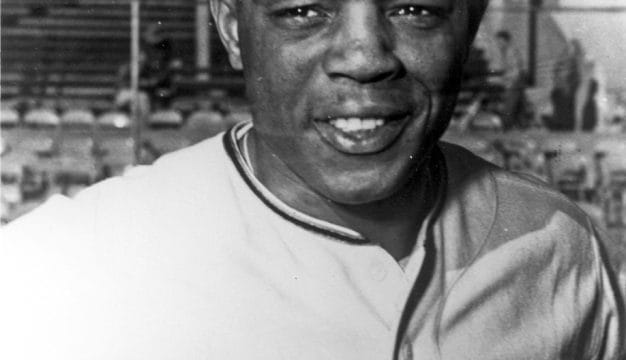

Virginia Durr and Rosa Parks

By the early 1950s, the Durrs were again living in Alabama, having moved to Montgomery in time to witness the civil rights movement. Given their long-standing commitment to ending segregation, it was perhaps inevitable that both the Durrs would become intimately involved in the struggle. Through their work for civil rights, the Durrs were acquainted with E. D. Nixon, who was head of the Montgomery branch of the Pullman Porters Union as well as president of the local NAACP chapter; Rosa Parks, who occasionally worked as a seamstress for the Durrs; and Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King. During Durr’s work with the SCHW, James Dombrowski had introduced her to the Highlander Folk School, of which he was a co-founder. Highlander was a settlement house in rural Tennessee that taught passive resistance techniques. She was immediately taken with the institution because of its work with miners and with labor unions. Because of her earlier association with Highlander, Virginia Durr was able to secure a scholarship for Rosa Parks to attend the school for two weeks in 1954. When Parks was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white man, Clifford Durr and E. D. Nixon bailed her out of jail. The Durrs continued their work for civil rights once the boycott was underway, with Clifford Durr advising civil rights attorney Fred Gray on the cases that challenged segregated transportation.

Virginia Durr and Rosa Parks

By the early 1950s, the Durrs were again living in Alabama, having moved to Montgomery in time to witness the civil rights movement. Given their long-standing commitment to ending segregation, it was perhaps inevitable that both the Durrs would become intimately involved in the struggle. Through their work for civil rights, the Durrs were acquainted with E. D. Nixon, who was head of the Montgomery branch of the Pullman Porters Union as well as president of the local NAACP chapter; Rosa Parks, who occasionally worked as a seamstress for the Durrs; and Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King. During Durr’s work with the SCHW, James Dombrowski had introduced her to the Highlander Folk School, of which he was a co-founder. Highlander was a settlement house in rural Tennessee that taught passive resistance techniques. She was immediately taken with the institution because of its work with miners and with labor unions. Because of her earlier association with Highlander, Virginia Durr was able to secure a scholarship for Rosa Parks to attend the school for two weeks in 1954. When Parks was arrested in 1955 for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus to a white man, Clifford Durr and E. D. Nixon bailed her out of jail. The Durrs continued their work for civil rights once the boycott was underway, with Clifford Durr advising civil rights attorney Fred Gray on the cases that challenged segregated transportation.

Durr, Virginia and Carr, Johnnie

For most of the 1960s, the Durr household was a hub of civil rights activity, as the Durrs opened their home to journalists, activists, historians, and attorneys who were drawn to Montgomery during the Freedom Rides or the Selma to Montgomery March. The Durrs were well-known in Montgomery, and their liberal politics and support for civil rights activists did not always endear them to their fellow white Alabamians. Frequently harassed and threatened, the Durrs eventually sent the two youngest of their five children to boarding schools outside the South after they were ostracized by teachers and classmates. Virginia’s experiences during the civil rights movement convinced her that poverty was the greatest problem afflicting the United States, and much of her later work grew out of that conviction.

Durr, Virginia and Carr, Johnnie

For most of the 1960s, the Durr household was a hub of civil rights activity, as the Durrs opened their home to journalists, activists, historians, and attorneys who were drawn to Montgomery during the Freedom Rides or the Selma to Montgomery March. The Durrs were well-known in Montgomery, and their liberal politics and support for civil rights activists did not always endear them to their fellow white Alabamians. Frequently harassed and threatened, the Durrs eventually sent the two youngest of their five children to boarding schools outside the South after they were ostracized by teachers and classmates. Virginia’s experiences during the civil rights movement convinced her that poverty was the greatest problem afflicting the United States, and much of her later work grew out of that conviction.

Clifford Durr died in 1975. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Virginia Durr continued to write and speak on behalf of progressive political causes. In 1985, she published her autobiography, Outside the Magic Circle, which was widely praised. She was active in state and local politics well into her early nineties, often protesting nuclear weapons and working to achieve economic equality. Durr died on February 24, 1999, at the age of 95. In the years since her death, Virginia Durr has been lauded as one the of the earliest and most loyal champions of civil rights. In 2003, much of her civil rights era correspondence was published by Patricia Sullivan as Freedom Writer: Virginia Foster Durr, Letters from the Civil Rights Years.

Additional Resources

Durr, Virginia Foster. Social Activism and Civil Rights. Microform. New York: Columbia University Oral History Collection, 1976.

———. Outside the Magic Circle: The Autobiography of Virginia Foster Durr, edited by Hollinger F. Barnard. 1985. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Sullivan, Patricia, and Virginia Foster Durr. Freedom Writer: Virginia Foster Durr, Letters from the Civil Rights Years. New York: Routledge, 2003.