Chickasaws in Alabama

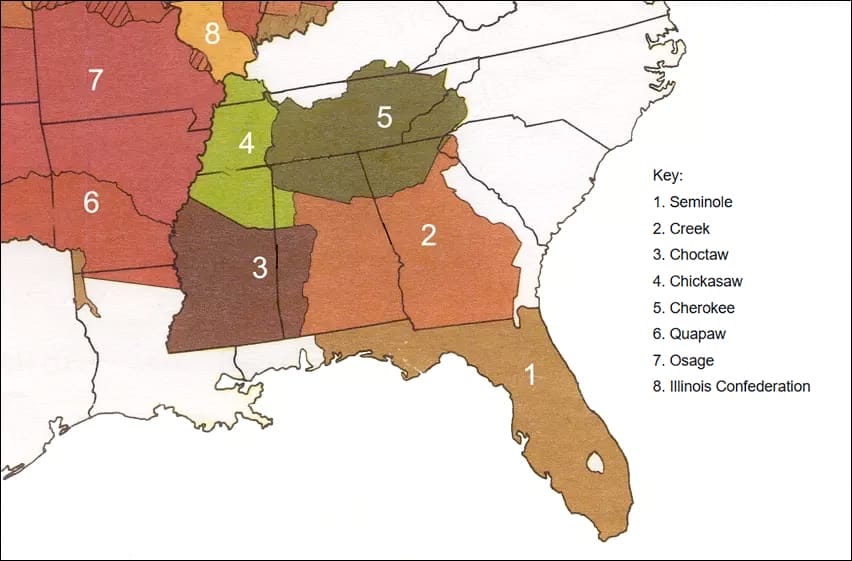

Sketch of Chickasaw Warrior, 1775

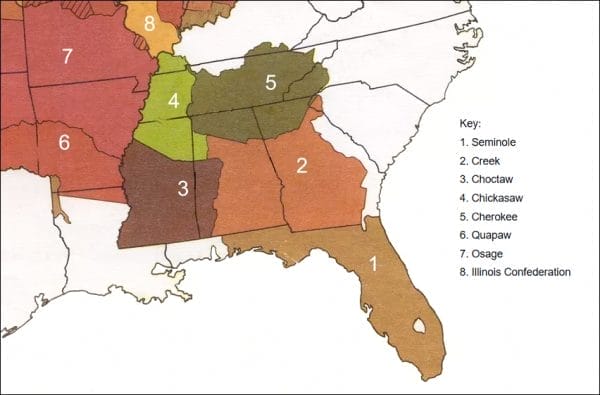

Although the Chickasaw Nation was primarily located in present-day Mississippi, their actions during the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century had a great impact on early Alabama history. The tribe successfully negotiated complicated trade and military alliances with the French, the British, and the U.S. government following the American Revolution. Despite their efforts to adapt to increasing numbers of white settlers after the war, they were eventually forced to cede their territory, along with the Creeks, Choctaws, and Cherokees, and remove to present-day Oklahoma. Today, the members of the Chickasaw Nation reside largely in 13 counties in south-central Oklahoma.

Sketch of Chickasaw Warrior, 1775

Although the Chickasaw Nation was primarily located in present-day Mississippi, their actions during the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century had a great impact on early Alabama history. The tribe successfully negotiated complicated trade and military alliances with the French, the British, and the U.S. government following the American Revolution. Despite their efforts to adapt to increasing numbers of white settlers after the war, they were eventually forced to cede their territory, along with the Creeks, Choctaws, and Cherokees, and remove to present-day Oklahoma. Today, the members of the Chickasaw Nation reside largely in 13 counties in south-central Oklahoma.

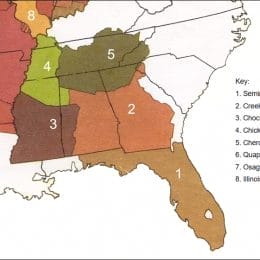

Chickasaw Lifeways

The Chickasaw Indians traditionally lived in what is now northwestern Alabama, northern Mississippi, and southwestern Tennessee. Their population fluctuated between 2,000 and 5,000 throughout the eighteenth century, and their villages were concentrated in the area of present-day Tupelo, Mississippi. Though smaller in numbers than other neighboring Indian tribes, such as the Creeks and the Choctaws, the Chickasaws’ impact on Alabama and the Southeast was significant.

The Chickasaws were culturally related to their southern neighbors the Choctaws. They spoke a dialect of the Western Muskogean language family shared by many of the Southeast’s Native American societies. Like all southeastern Indians, the Chickasaws traced lineage according to matrilineal rules of kinship, which meant an individual was only related to his or her mother’s family and that the primary father figure in a child’s life was likely a maternal uncle rather than the biological father. Chickasaw women controlled their own resources and land, where they raised the crops that all Chickasaws depended upon. By the eighteenth century, the Chickasaws lived in approximately 10 towns in northeastern Mississippi and in other locations among the Upper Creeks from 1722 to 1740 and farther east along the Savannah River from 1723 until around 1776. Following the Natchez War against the French in 1729, a contingent of Natchez people joined the Chickasaws as a separate village. Each village maintained its own set of war chiefs, civil chiefs, and other officers that may have been determined by clan membership, with 15 distinct clans. The Chickasaw villages fell into one of two basic groupings, or moieties, called the Spanish clan or Panther clan, and each division maintained its own ritualistic leaders and governance.

Contact with European Explorers

Chickasaw Beaded Cap

The Chickasaws’ first interactions with Europeans occurred during the winter of 1540-41, when they repeatedly attacked Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his expedition until they moved west across the Mississippi River, culminating in a major engagement on March 4, 1541, when the Chickasaws nearly overran Soto’s forces and killed 12 Spaniards, 56 horses, and hundreds of pigs. Those brief encounters were the only significant contact that the Chickasaws had with Europeans until the founding of Charles Town (Charleston) in Carolina by the English in 1670. British traders sought to trade guns, metal goods, manufactured cloth, and other items with the Chickasaws for deerskins and Indian captives, who were then sold as slaves to sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The Chickasaws became prominent slave traders in the early colonial South at the expense of their Indian neighbors, enhancing their wealth and political position as middlemen between the British and other tribes. French explorers and traders, who had established a presence on the Gulf Coast, chose to trade with their principal Indian allies, the Choctaws, to the dismay of the Chickasaws. Partly for this reason, around 200 Chickasaws, led by chief Squirrel King, relocated farther east to the Savannah River in the 1720s to be nearer the English and their trade goods.

Chickasaw Beaded Cap

The Chickasaws’ first interactions with Europeans occurred during the winter of 1540-41, when they repeatedly attacked Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his expedition until they moved west across the Mississippi River, culminating in a major engagement on March 4, 1541, when the Chickasaws nearly overran Soto’s forces and killed 12 Spaniards, 56 horses, and hundreds of pigs. Those brief encounters were the only significant contact that the Chickasaws had with Europeans until the founding of Charles Town (Charleston) in Carolina by the English in 1670. British traders sought to trade guns, metal goods, manufactured cloth, and other items with the Chickasaws for deerskins and Indian captives, who were then sold as slaves to sugar plantations in the Caribbean. The Chickasaws became prominent slave traders in the early colonial South at the expense of their Indian neighbors, enhancing their wealth and political position as middlemen between the British and other tribes. French explorers and traders, who had established a presence on the Gulf Coast, chose to trade with their principal Indian allies, the Choctaws, to the dismay of the Chickasaws. Partly for this reason, around 200 Chickasaws, led by chief Squirrel King, relocated farther east to the Savannah River in the 1720s to be nearer the English and their trade goods.

Conflict with the Choctaws and the French

The Chickasaws’ close relations with the English led the French, under Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, into conflict with the tribe that lasted for several decades and had a ruinous effect. The French colonial government could not afford to trade with all Indians in the lower Mississippi Valley, and they chose to cut their losses by cultivating the large Choctaw population as allies to the exclusion of some smaller groups such as the Chickasaws. Beginning in 1720, the Chickasaws sparked a conflict with the French and their Choctaw allies after Chickasaw warriors killed a French fur trader whom they and the English accused of being a spy. In retaliation, the French provided more guns and ammunition to the Choctaws and encouraged them to attack the Chickasaws. All of the Choctaw assaults were repelled by the Chickasaw, who then went on the offensive and effectively cut off all French shipping on the Mississippi River. The Chickasaws and Choctaws established peace in 1724 and the French agreed to abide by the new agreement in 1725.

The peace agreement was short-lived, however. In November 1729, the Natchez Indians rebelled against the French settlers in their midst, killing more than 200 of them. When the French retaliated in force, they killed many Natchez and took still more as prisoners. Natchez survivors were forced to abandon their home territory, and many of them sought refuge among the Chickasaws sometime around 1730 or 1731 in what is now Lee County, Mississippi, further angering the French. In 1736, the French and Choctaws launched a coordinated attack from the north and south against Chickasaw villages in northeast Mississippi that failed miserably, despite a nearly three-to-one advantage over the defenders. In 1739, the French mounted a new effort against the Chickasaws that also failed, and the two parties signed a truce in 1740. The Chickasaws again established peace with the Choctaws during the French and Indian War, ending decades of conflict, and Britain’s defeat of the French in 1763 removed them as a threat. The Chickasaws had survived France’s attempt to destroy them, but their population had dropped dramatically to about 3,000 during this period as a result of the constant warfare.

The American Revolution

With their ally and long-time trading partner Great Britain in control of much of the eastern territory of the Gulf of Mexico and east of the Mississippi River after 1763, the Chickasaws experienced few threats. In 1765, tribal leaders representing the Chickasaws and Choctaws met with British negotiator and former French officer Henrí Montault de Monbéraut de Saint-Çivier in Mobile under the auspices of George Johnstone, governor of British West Florida, and signed the Treaty with the Choctaws and Chickasaws. That agreeable situation ended, however, when the American Revolution erupted in 1776. The Chickasaws tried to remain neutral, but they felt most committed to the British cause because of the long history between the two nations. The only battle between the Chickasaws and Americans during the war occurred in 1780, when some Chickasaws briefly attacked George Rogers Clark’s Fort Jefferson in western Kentucky. After the war the Chickasaws quickly established relations with the United States and with Spain, which controlled the entire Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas.

During the 1780s and 1790s, the Chickasaws played the United States and Spain off of one another, trading with both countries while refusing to be dominated by either. Skillful diplomacy had always been important for the Chickasaws in retaining their sovereignty, but in 1795, under the Treaty of San Lorenzo (also called Pinckney’s Treaty), Spain ceded all claims to land above the 31st parallel, thus placing all Chickasaw lands within the boundaries of the United States. The Mississippi Territory (including present-day Alabama) was formed three years later in 1798, and Americans flooded into lands along the Mississippi River and then along the Natchez Trace, which crossed through the middle of Chickasaw lands. By 1809 there were an estimated 5,000 American squatters living on Chickasaw land.

Land Cessions

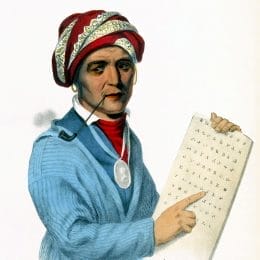

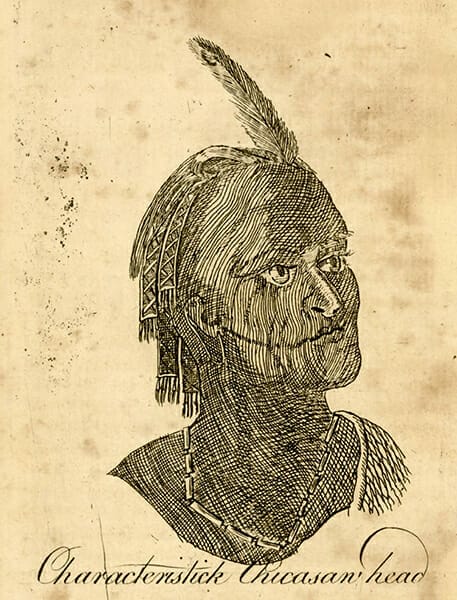

Chickasaw Territory in Alabama, 1824

Beginning with a treaty at Chickasaw Bluffs in 1801, in which the Chickasaws granted the United States permission to build the Natchez Trace through their territory, the Chickasaws slowly ceded their claims to land. In 1805, in the Treaty of Chickasaw Nation, the Chickasaws ceded some claims to land north of the Tennessee River, including part of north Alabama, in order to pay debts owed to trading companies. Despite their support of the United States against the Red Stick Creeks during the War of 1812, the Chickasaws were forced to sign a treaty with Andrew Jackson in 1816 that ceded their remaining claims to land north and east of the Tennessee River, including parts of north Alabama. Two years later, in the Great Chickasaw Cession, the Chickasaws ceded all remaining claims to land in Tennessee and western Kentucky. The Colbert family, especially William and George, played a significant role in promoting these land cessions among their fellow Chickasaws after the War of 1812. As members of the Chickasaw tribe with bi-lingual speaking and writing skills and business interests, the Colberts parlayed their Chickasaw ethnicity, education, and entrepreneurial spirit into political power.

Chickasaw Territory in Alabama, 1824

Beginning with a treaty at Chickasaw Bluffs in 1801, in which the Chickasaws granted the United States permission to build the Natchez Trace through their territory, the Chickasaws slowly ceded their claims to land. In 1805, in the Treaty of Chickasaw Nation, the Chickasaws ceded some claims to land north of the Tennessee River, including part of north Alabama, in order to pay debts owed to trading companies. Despite their support of the United States against the Red Stick Creeks during the War of 1812, the Chickasaws were forced to sign a treaty with Andrew Jackson in 1816 that ceded their remaining claims to land north and east of the Tennessee River, including parts of north Alabama. Two years later, in the Great Chickasaw Cession, the Chickasaws ceded all remaining claims to land in Tennessee and western Kentucky. The Colbert family, especially William and George, played a significant role in promoting these land cessions among their fellow Chickasaws after the War of 1812. As members of the Chickasaw tribe with bi-lingual speaking and writing skills and business interests, the Colberts parlayed their Chickasaw ethnicity, education, and entrepreneurial spirit into political power.

Along with growing pressure on the Chickasaws to cede their lands came cultural and economic change. Chickasaw chiefs, including some of the Colberts, led a new effort to encourage the production of renewable resources, such as cattle and cotton, in order to establish a market economy among the Chickasaws and move away from their dependence on the deerskin trade. Along with these new agricultural pursuits, the Chickasaws embraced slave ownership, constitutional government, and private land ownership. In addition, the role of women began to mirror American mainstream values. Whereas Chickasaw women had been the farmers and owners of land, new economic realities placed them in a more subservient role to their husbands.

Assimilation and Removal

Protestant missionaries arrived among the Chickasaws in the early nineteenth century, teaching Christianity, writing, arithmetic, husbandry, and domestic skills. The U.S. government, through its “plan of civilization,” urged the Chickasaws and other southeastern Indians to adopt mainstream American culture as a path to becoming American citizens. Although many Chickasaws did adopt the values, economics, and religion of their American neighbors, white residents of Mississippi and Alabama insisted that Indians had no right to possess lands that more “civilized”—by which they meant European American—citizens could own and farm.

After the U.S. government passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, Chickasaw leaders sought to acquire the best terms possible, especially members of the extended Colbert family, who sought special provisions and guarantees of extra money or land claims. That summer, tribal representatives met with U.S. delegates, including Pres. Andrew Jackson, and a treaty was signed on August 31 at Franklin, Tennessee. The Chickasaws agreed to cede their two million acres in Alabama and Mississippi in exchange for an equal amount of land to the west, but this treaty was voided when a suitable area could not be found. A new treaty was signed in 1832 in Chickasaw territory at Pontotoc Creek in present-day Pontotoc County, Mississippi, under which the Chickasaw ceded all their remaining lands, including an area in northwest Alabama south of the Tennessee River, to the U.S. government in exchange for lands in present-day Oklahoma. The lands were surveyed and quickly sold, with each adult Chickasaw receiving a temporary individual land allotment that was also sold, with all monies placed in a fund to cover the costs of removal. Alabama and Mississippi settlers quickly occupied the Chickasaw lands beginning in 1832, as they had been doing illegally by the hundreds since the mid-1820s. Chickasaw removal took years, because suitable land in the west could not be found. Most Chickasaws did not arrive in Indian Territory until 1838, after a January 1837 meeting between the Chickasaws and Choctaws at Doaksville, Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory, at which the Choctaws sold the western part of their new territory to the Chickasaws. The last Chickasaws did not leave north Mississippi until 1850.

Further Reading

- Adair, James. The History of the American Indians. Kathryn Holland Braund, ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.

- Atkinson, James R. Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Fitzgerald, David G. Chickasaw: Unconquered and Unconquerable. Ada, Okla.: Chickasaw Press, 2006.

- Gibson, Arrell M. The Chickasaws. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

- Hoyt, Anne Kelley. Bibliography of the Chickasaw. Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1987.

- Scrivner, Fulsom Charles. The Early Chickasaws: Profile of Courage. New York: Vantage Press, 2005.

- Swanton, John R. Chickasaw Society and Religion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.