Biodiversity in Alabama

White-topped Pitcher Plant

Alabama is one of the most biologically diverse states in the United States and is a global hotspot of diversity for several groups of plants and animals. This diversity is a product of Alabama’s climate, geologic diversity, and rich evolutionary past. With more than 6,350 species, Alabama ranks fourth among states in terms of species diversity and is first among states east of the Mississippi River. The large western states of California, Texas, and Arizona lead the nation, respectively, and fellow southeastern states Georgia (fifth) and Florida (seventh) are right behind Alabama. Supporting this diversity are 64 types of terrestrial ecosystems, including 25 forests and woodlands, 11 wetlands, and seven glades and prairies. The state also has more than 132,000 miles of rivers and streams and several dozen marine ecosystems.

White-topped Pitcher Plant

Alabama is one of the most biologically diverse states in the United States and is a global hotspot of diversity for several groups of plants and animals. This diversity is a product of Alabama’s climate, geologic diversity, and rich evolutionary past. With more than 6,350 species, Alabama ranks fourth among states in terms of species diversity and is first among states east of the Mississippi River. The large western states of California, Texas, and Arizona lead the nation, respectively, and fellow southeastern states Georgia (fifth) and Florida (seventh) are right behind Alabama. Supporting this diversity are 64 types of terrestrial ecosystems, including 25 forests and woodlands, 11 wetlands, and seven glades and prairies. The state also has more than 132,000 miles of rivers and streams and several dozen marine ecosystems.

Alabama Beach Mouse

Alabama ranks first among states or is near the top for several types of animals and plants. It is number one for diversity of freshwater mussels, freshwater fishes, freshwater snails, crayfish, and freshwater turtles. It is fourth for combined diversity of amphibians and reptiles and fifth for salamanders. Alabama is also first in carnivorous plant biodiversity and is one of the world’s hotspots for these unusual organisms. The extensive cave system in the northeastern part of the state harbors the third most biodiverse cave fauna in the temperate world. Considering that only a fraction of these caverns has been explored, Alabama’s eventual ranking may be at the very top. For plants, birds, and mammals Alabama ranks lower, at the 9th, 14th, and 39th position among U.S. states, respectively.

Alabama Beach Mouse

Alabama ranks first among states or is near the top for several types of animals and plants. It is number one for diversity of freshwater mussels, freshwater fishes, freshwater snails, crayfish, and freshwater turtles. It is fourth for combined diversity of amphibians and reptiles and fifth for salamanders. Alabama is also first in carnivorous plant biodiversity and is one of the world’s hotspots for these unusual organisms. The extensive cave system in the northeastern part of the state harbors the third most biodiverse cave fauna in the temperate world. Considering that only a fraction of these caverns has been explored, Alabama’s eventual ranking may be at the very top. For plants, birds, and mammals Alabama ranks lower, at the 9th, 14th, and 39th position among U.S. states, respectively.

The Influence of Climate

Alabama’s location on the planet, between 30 and 35 degrees north latitude, means that it receives an abundance of sunlight, more so than states farther north. Thus, Alabama’s ecosystems have a relatively high rate of biological productivity, the amount of all solar energy captured by plants in an ecosystem over time. Alabama’s latitude also allows for a relatively long growing season, which further boosts biological productivity. Indeed, the top seven U.S. states for biodiversity are positioned along the nation’s southern border.

Abundant water resources also boost biological productivity, and Alabama is very wet. The Deep South competes with the Pacific Northwest as the rainiest region in the country but is much more biologically diverse because it is warmer. The waters of the Gulf of Mexico are an important factor in Alabama’s climate, especially the influence of the Loop Current. Throughout the year, this current enters from the Caribbean Sea between Cuba and the Yucatan Peninsula, heads north toward Alabama, then bends to the southeast and exits the Gulf via the Florida Straits. In the process, the Loop Current delivers warm tropical waters to Alabama’s doorstep. Evaporation from the northern Gulf provides water vapor that falls on the state as rain throughout the year. A glance at any world map will reveal that deserts are usually found at Alabama’s latitude. Because of the Gulf of Mexico, however, Alabama and its neighboring states are lush and green.

Cahaba Indian Paintbrush

High levels of heat and moisture can also produce volatile weather patterns, but these, too, enhance the state’s species biodiversity. Convective storms generate lightning, and the resulting wildfires have kept the Southeast burning for thousands of years. The role that fire plays in shaping the biodiversity of the region cannot be overstated. Prior to statehood, a combination of Native American landscape management and lightning-sparked fires meant that most of the state would burn at least once a decade, often more. These fires maintained prairies and open woodlands and prevented fast-growing shrubs and trees from overtaking ecosystems. The plentiful sunlight reaching the ground supported hundreds of less-competitive, sun-loving species, especially wildflowers and grasses. These species evolved strategies to cope with the frequent, low-intensity fires. Within the longleaf pine woodland (Alabama’s most widespread native ecosystem), it is possible to find more than 30 fire-adapted species per square meter of soil.

Cahaba Indian Paintbrush

High levels of heat and moisture can also produce volatile weather patterns, but these, too, enhance the state’s species biodiversity. Convective storms generate lightning, and the resulting wildfires have kept the Southeast burning for thousands of years. The role that fire plays in shaping the biodiversity of the region cannot be overstated. Prior to statehood, a combination of Native American landscape management and lightning-sparked fires meant that most of the state would burn at least once a decade, often more. These fires maintained prairies and open woodlands and prevented fast-growing shrubs and trees from overtaking ecosystems. The plentiful sunlight reaching the ground supported hundreds of less-competitive, sun-loving species, especially wildflowers and grasses. These species evolved strategies to cope with the frequent, low-intensity fires. Within the longleaf pine woodland (Alabama’s most widespread native ecosystem), it is possible to find more than 30 fire-adapted species per square meter of soil.

The Influence of Geologic Diversity

Alabama’s rich geologic diversity has shaped the state’s ecosystems and biodiversity even more than climate. Variations in soil types, bedrock exposure, and topography regulate biological productivity by affecting the availability of heat, light, water, and nutrients. In general, regions with more geologic variation have more species. Alabama has a high degree of geologic variation relative to most other southeastern states because of the many rock types uplifted by the rise of the Southern Appalachian Mountains during the final 170 million years of the Paleozoic Era (541-252 million years ago).

Demopolis Chalk

Alabama has many unique ecosystems made possible by its variety of soils. For example, the quartz sand deposits along the coast support dune communities sparsely populated by grasses and shrubs. Though rain frequently drenches the coast, water quickly drains through the dune sand, and the resulting ecosystem is more akin to desert than any other ecosystem in the state. In contrast, the marine chalks of the Blackland Prairie region supported tallgrass prairies before they were converted to cotton plantations. Trees were kept out by frequent fire and the dense chalk, which was nearly impenetrable to tree roots and groundwater. Instead, grasses and wildflowers more typical of the tallgrass prairies of the Great Plains presided.

Demopolis Chalk

Alabama has many unique ecosystems made possible by its variety of soils. For example, the quartz sand deposits along the coast support dune communities sparsely populated by grasses and shrubs. Though rain frequently drenches the coast, water quickly drains through the dune sand, and the resulting ecosystem is more akin to desert than any other ecosystem in the state. In contrast, the marine chalks of the Blackland Prairie region supported tallgrass prairies before they were converted to cotton plantations. Trees were kept out by frequent fire and the dense chalk, which was nearly impenetrable to tree roots and groundwater. Instead, grasses and wildflowers more typical of the tallgrass prairies of the Great Plains presided.

Scattered throughout Alabama’s coastal plains are seepage bogs, wetlands created by groundwater forced to remain on the surface by a thick layer of nonporous clay. These sunny wetlands support wildflowers, grasses, and most of the state’s carnivorous plant species.

Leafy Prairie Clover

Alabama’s glade ecosystems offer the most dramatic example of the connection between geology and biological diversity. Found in the mountainous region of the state, glades are open, sunny ecosystems where the bedrock is at the surface or covered with extremely thin soils. Because trees struggle to gain a foothold, the soils support rare and unusual wildflowers that can tolerate the harsh conditions. Most glade plants complete their growth and reproduction in a few weeks in late spring, before the glades become unbearably hot. Glade types are named for their bedrock and Alabama glades include limestone, dolostone, sandstone, and granite. Each rock type weathers into a unique soil and supports a distinct assemblage of plant species.

Leafy Prairie Clover

Alabama’s glade ecosystems offer the most dramatic example of the connection between geology and biological diversity. Found in the mountainous region of the state, glades are open, sunny ecosystems where the bedrock is at the surface or covered with extremely thin soils. Because trees struggle to gain a foothold, the soils support rare and unusual wildflowers that can tolerate the harsh conditions. Most glade plants complete their growth and reproduction in a few weeks in late spring, before the glades become unbearably hot. Glade types are named for their bedrock and Alabama glades include limestone, dolostone, sandstone, and granite. Each rock type weathers into a unique soil and supports a distinct assemblage of plant species.

Geologic processes also created the state’s diverse topography, the arrangement of surface features such as mountains, plains, and rivers. Alabama’s terrain ranges from the flat Coastal Plain section to the rugged peaks of the Valley and Ridge section in the state’s northeast. Each of Alabama’s five physiographic sections has a distinctive topography, and this variation promotes ecological and species diversity. Each province supports its own distinctive set of soils and topography, and consequently, a distinctive community of plants and animals.

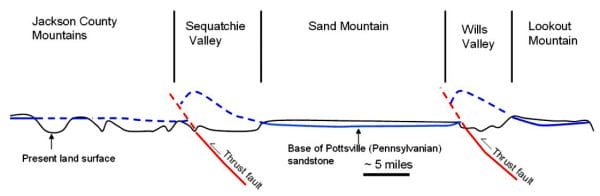

Cumberland Plateau Cross-Section

In the southern Cumberland Plateau section, for example, different rates of erosion have produced a template upon which many varied ecosystems survive side by side. Broad mountains with relatively flat upper surfaces—including Sand and Lookout Mountains—dominate the landscape. These plateaus persist because a cap of sandstone (a very durable rock) underlies the surface and resists erosion. The valleys adjacent to the plateaus exist where the sandstone cap fractured as the Southern Appalachian Mountains grew. Water eroded the fragments away, then cut downward through the shale, limestone, and other soft rocks beneath.

Cumberland Plateau Cross-Section

In the southern Cumberland Plateau section, for example, different rates of erosion have produced a template upon which many varied ecosystems survive side by side. Broad mountains with relatively flat upper surfaces—including Sand and Lookout Mountains—dominate the landscape. These plateaus persist because a cap of sandstone (a very durable rock) underlies the surface and resists erosion. The valleys adjacent to the plateaus exist where the sandstone cap fractured as the Southern Appalachian Mountains grew. Water eroded the fragments away, then cut downward through the shale, limestone, and other soft rocks beneath.

Elf Orpine Flowers

Up on the plateau surface, weathering of the sandstone produces well-drained sandy soils. Before white settlers arrived and cleared them for agriculture, the plateau surface supported dry, open woodlands through which wildfire burned once or twice a decade. Shortleaf pine and a handful of fire-tolerant oak species dominated. Interspersed within these woodlands were dry glades on flat exposures of particularly durable sandstone. Some of these glades still exist because they cannot support agriculture. These glades harbor rare plants such as the Little River Canyon onion (Allium speculae) and the elf orpine (Diamorpha smallii). Low spots on the plateau collect groundwater and support bogs with green pitcher plants (Sarracenia oreophila). At the margin of the plateau, where the sandstone caprock ends, a steep escarpment stretches down to the valley below. The escarpment supports lush broadleaf forests and a handful of other wet ecosystems where fire is absent, such as acidic cliffs and heath bluff forests. The plants and animals in these ecosystems differ from those living on the plateau above.

Elf Orpine Flowers

Up on the plateau surface, weathering of the sandstone produces well-drained sandy soils. Before white settlers arrived and cleared them for agriculture, the plateau surface supported dry, open woodlands through which wildfire burned once or twice a decade. Shortleaf pine and a handful of fire-tolerant oak species dominated. Interspersed within these woodlands were dry glades on flat exposures of particularly durable sandstone. Some of these glades still exist because they cannot support agriculture. These glades harbor rare plants such as the Little River Canyon onion (Allium speculae) and the elf orpine (Diamorpha smallii). Low spots on the plateau collect groundwater and support bogs with green pitcher plants (Sarracenia oreophila). At the margin of the plateau, where the sandstone caprock ends, a steep escarpment stretches down to the valley below. The escarpment supports lush broadleaf forests and a handful of other wet ecosystems where fire is absent, such as acidic cliffs and heath bluff forests. The plants and animals in these ecosystems differ from those living on the plateau above.

Evolutionary Past

Alabama’s varied topography and soils are the product of hundreds of millions of years of geologic history. The landscape has been shaped by an ever-shifting climate, the rise and erosion of mountains, stream and river formation, and changes in sea level. These changes shaped the ecosystems that we have today and triggered the evolution of many new species.

The process of new species formation, known as speciation, can occur via several evolutionary pathways. A frequent method begins when a unified population becomes fractured into two or more isolated populations. The barrier separating the populations must be a habitat that is impossible for the organism to traverse. Geology is frequently involved because geologic processes (e.g., shifting rivers, changing sea levels, mountain formation) often cause and enforce the isolation. Over long periods of time the isolated populations diverge genetically as they adapt to their unique environments. With sufficient genetic change, the populations become new species.

Red Hills Salamander

Salamanders are one of several groups of southeastern organisms that are famous among biologists for their degree of speciation. The United States has more species of salamander than any other country in the world, and that diversity is centered in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, which begin near Birmingham and extend northeastward in the state. These mountains harbor more than 40 species and subspecies of salamander. The salamander species of the family known as Plethodontidae have undergone multiple speciation events and comprise more than half the salamander species in Alabama. Scientists believe the origins of the Plethodontidae date to the Jurassic period (201-145 million years ago), when an ancestral lineage of salamanders evolved to endure drier conditions and then spread across the northern hemisphere, including the Appalachians. During warm, wet periods their ranges expanded, but during lengthy cool, dry periods, populations retreated to and became isolated in mountain valleys. Many of these isolated populations evolved into new species found only in the Southeast.

Red Hills Salamander

Salamanders are one of several groups of southeastern organisms that are famous among biologists for their degree of speciation. The United States has more species of salamander than any other country in the world, and that diversity is centered in the Southern Appalachian Mountains, which begin near Birmingham and extend northeastward in the state. These mountains harbor more than 40 species and subspecies of salamander. The salamander species of the family known as Plethodontidae have undergone multiple speciation events and comprise more than half the salamander species in Alabama. Scientists believe the origins of the Plethodontidae date to the Jurassic period (201-145 million years ago), when an ancestral lineage of salamanders evolved to endure drier conditions and then spread across the northern hemisphere, including the Appalachians. During warm, wet periods their ranges expanded, but during lengthy cool, dry periods, populations retreated to and became isolated in mountain valleys. Many of these isolated populations evolved into new species found only in the Southeast.

American Beech

The state’s diverse array of plant species derives largely from the Pleistocene (2.6 million years ago to 12,000 years ago). Many plant species in the Appalachian forests share a peculiar biogeographic pattern in that they are very closely related to species in East Asia. The two regions share more than 100 plant genera (the classification level just above species), including wildflowers such as mayapple, ginseng, and jack-in-the-pulpit, and trees such as beech, catalpa, chestnut, oak, and tulip poplar. In fact, the two floras are more alike than either is to the neighboring floras of western North America and Europe. The beginnings of this pattern emerged in the Early Tertiary period (66-50 million years ago), when a vast deciduous forest encircled the Northern Hemisphere. Species migrated from continent to continent across temporary land bridges. Later, during the Pleistocene, advancing glaciers forced temperate forests southward. In Europe and Central Asia, mountains trending east to west blocked the migration of plant species to warmer latitudes to the south, and this type of forest disappeared. In the United States and East Asia, however, mountains aligned north-to-south helped species to migrate. This arrangement split apart many plant species populations, with the frigid arctic temperatures and the oceans keeping them isolated from one another. Today, thousands of years later, these isolated populations have evolved into new species.

American Beech

The state’s diverse array of plant species derives largely from the Pleistocene (2.6 million years ago to 12,000 years ago). Many plant species in the Appalachian forests share a peculiar biogeographic pattern in that they are very closely related to species in East Asia. The two regions share more than 100 plant genera (the classification level just above species), including wildflowers such as mayapple, ginseng, and jack-in-the-pulpit, and trees such as beech, catalpa, chestnut, oak, and tulip poplar. In fact, the two floras are more alike than either is to the neighboring floras of western North America and Europe. The beginnings of this pattern emerged in the Early Tertiary period (66-50 million years ago), when a vast deciduous forest encircled the Northern Hemisphere. Species migrated from continent to continent across temporary land bridges. Later, during the Pleistocene, advancing glaciers forced temperate forests southward. In Europe and Central Asia, mountains trending east to west blocked the migration of plant species to warmer latitudes to the south, and this type of forest disappeared. In the United States and East Asia, however, mountains aligned north-to-south helped species to migrate. This arrangement split apart many plant species populations, with the frigid arctic temperatures and the oceans keeping them isolated from one another. Today, thousands of years later, these isolated populations have evolved into new species.

Vermilion Darter

The most dramatic evolutionary influence of the Southern Appalachian Mountains has been on Alabama’s freshwater fauna. When the Appalachians fractured the southeastern landscape into multiple watersheds, the fragmentation created many opportunities for isolation and speciation. This was especially true for fishes, snails, mussels, and crayfish because all are easily isolated in the shallow streams in the headwaters of major rivers. Consequently, more freshwater species are found in the Southeast than in any other place outside of the wet tropics. Alabama is at the center of this aquatic biodiversity hotspot. Speciation was especially rampant in the Tennessee River and the Mobile River Basin. An extreme case is the vermilion darter, a species restricted to one small watershed, Turkey Creek, in Jefferson County.

Vermilion Darter

The most dramatic evolutionary influence of the Southern Appalachian Mountains has been on Alabama’s freshwater fauna. When the Appalachians fractured the southeastern landscape into multiple watersheds, the fragmentation created many opportunities for isolation and speciation. This was especially true for fishes, snails, mussels, and crayfish because all are easily isolated in the shallow streams in the headwaters of major rivers. Consequently, more freshwater species are found in the Southeast than in any other place outside of the wet tropics. Alabama is at the center of this aquatic biodiversity hotspot. Speciation was especially rampant in the Tennessee River and the Mobile River Basin. An extreme case is the vermilion darter, a species restricted to one small watershed, Turkey Creek, in Jefferson County.

Biodiversity and the Twenty-First Century

Alabama’s ecosystems and species have not been as well-studied as those of most other states. With the state now enjoying more scientific attention, there will likely be hundreds of new species discovered in Alabama this century. Just in the first decade, at least 76 species new to science were discovered in Alabama. This list includes the Red Hills azalea; two pancake batfishes; an 11-inch-long Tennessee bottlebrush crayfish; several cave species, including two crayfish; three flesh flies that breed in pitcher plants; several fishes, including the Tallapoosa sculpin and the Alabama bass; the cypress floater (a mussel); 32 plants, most being wildflowers; and two trapdoor spiders, one named after musician Neil Young (Myrmekiaphila neilyoungi) and the other named after Auburn University’s tiger mascot (Myrmekiaphila tigris).

Kudzu Devouring Building, near Greensboro, Alabama

While there is much to celebrate about Alabama’s biodiversity, there are also many dangerous trends. With 82 extinct species, Alabama ranks second in the United States for total extinctions (species that have disappeared forever). What’s more, the state ranks third for the number of species on the U.S. endangered species list. Many of these species have populations that are declining. Habitat loss and degradation, especially water pollution and the damming of rivers, have caused the great majority of these extinctions and endangerments. Pollution, non-native invasive species, and climate change are also forcing many species towards endangerment and extinction.

Kudzu Devouring Building, near Greensboro, Alabama

While there is much to celebrate about Alabama’s biodiversity, there are also many dangerous trends. With 82 extinct species, Alabama ranks second in the United States for total extinctions (species that have disappeared forever). What’s more, the state ranks third for the number of species on the U.S. endangered species list. Many of these species have populations that are declining. Habitat loss and degradation, especially water pollution and the damming of rivers, have caused the great majority of these extinctions and endangerments. Pollution, non-native invasive species, and climate change are also forcing many species towards endangerment and extinction.

As Alabama’s ecosystems lose their species, the quality of “services” provided by these ecosystems declines. Ecosystem services are beneficial processes that ecosystems provide to humanity. They include supplying freshwater for drinking and irrigation, providing places for outdoor recreation, and absorbing floodwaters. Without ecosystem services, life as we know it could not exist in Alabama or anywhere. The link between these services and biodiversity is that ecosystems provide more services and better-quality services when their native species are present and their populations are strong. Thus, declines in biodiversity threatens our economy, culture, and quality of life. Conversely, when we protect biodiversity, we are protecting ourselves and future generations.

Further Reading

- Duncan, Scot. Southern Wonder: Alabama’s Surprising Biodiversity. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013.

- Boschung, Herbert T., and Richard L. Mayden. Fishes of Alabama. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2004.

- Lacefield, Jim. Lost Worlds in Alabama Rocks: A Guide to the State’s Ancient Life and Landscapes. Rev. ed. Tuscaloosa: Alabama Geological Society, 2013.

- Schuster, Guenter A., Christopher A. Taylor, and Stuart W. McGregor. Crayfishes of Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2022.

- Stein, Bruce A. States of the Union: Ranking America’s Biodiversity. Arlington, Va.: NatureServe, 2002.

- Stein, Bruce A., Lynn S. Kutner, and Jonathon S. Adams, eds. Precious Heritage: The Status of Biodiversity in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Williams, James D., Arthur E. Bogan, and Jeffrey T. Garner. Freshwater Mussels of Alabama and the Mobile Basin in Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.