Secession

William Lowndes Yancey

Secession is the doctrine that the people of each state, having voluntarily entered the Union, have the right to withdraw from it whenever they come to believe that continued membership represents a threat to their liberties. This prerogative was declared to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1869 in the case of Texas v. White, but earlier in the nineteenth century it had been widely discussed. As northern attacks on the institution of slavery began to mount, beginning with the controversy over the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-20, pro-slavery extremists in Alabama and other southern states increasingly referred to secession as their ultimate defense to protect their region’s society and economy.

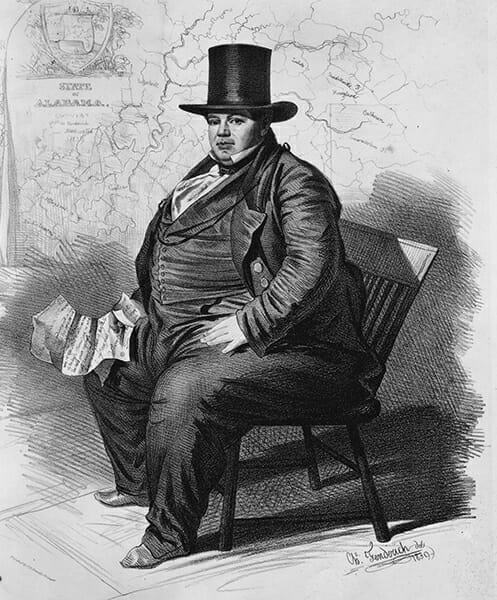

William Lowndes Yancey

Secession is the doctrine that the people of each state, having voluntarily entered the Union, have the right to withdraw from it whenever they come to believe that continued membership represents a threat to their liberties. This prerogative was declared to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1869 in the case of Texas v. White, but earlier in the nineteenth century it had been widely discussed. As northern attacks on the institution of slavery began to mount, beginning with the controversy over the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-20, pro-slavery extremists in Alabama and other southern states increasingly referred to secession as their ultimate defense to protect their region’s society and economy.

During the nullification crisis of 1828-33 in South Carolina, a small group of Alabamians who admired South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun’s radical states’ rights principles coalesced under the leadership of congressman and future senator Dixon Hall Lewis of Lowndes County. These Calhounites, as they became known, accepted Calhoun’s warning that national parties inevitably caused their members to compromise their principles in pursuit of political victory, and therefore that for southerners, party membership would always mean making concessions to the northern opponents of southern interests. They consequently attempted to remain aloof from the developing two-party system. But as the Democratic and Whig parties began to take final form in 1839, in preparation for the presidential election of 1840, the Calhounites reluctantly cast their lot with the Democrats. Though the Calhounites were deeply hostile to the Whigs’ desire for a vigorous national program of economic development, they were never really in sympathy with the anti-planter, anti-corporate beliefs of the Democrats’ overwhelming Jacksonian majority.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Following Dixon Lewis’s death in 1848, the leadership of the Calhounite faction passed to Montgomery attorney William Lowndes Yancey. In the developing crisis over the admission of California as a free state during 1848-50, Yancey and his allies attempted to push the state’s Democrats into adopting an extreme southern rights stance. But with the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which balanced California’s admission with a number of other provisions including a law facilitating the recovery of slaves who had fled into the free states, pro-Compromise Democrats formed a coalition with the Whigs and trounced Yancey’s southern rights candidates in the state elections of 1851. In the presidential election of 1852, the Yanceyites ran their own candidates for president and vice-president—George M. Troup of Georgia and John A. Quitman of Mississippi, respectively—against both the Democratic and the Whig nominees. They received just 4.6 percent of the poll and carried only Barbour and Lowndes Counties. It is clear, in short, that as late as the early 1850s, the Yanceyites still had the backing of only a tiny handful of Alabama voters. The developments that would lead the state to secession turned on the dissolution of the Whig Party and the rise of Yancey’s faction among the Democrats following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Following Dixon Lewis’s death in 1848, the leadership of the Calhounite faction passed to Montgomery attorney William Lowndes Yancey. In the developing crisis over the admission of California as a free state during 1848-50, Yancey and his allies attempted to push the state’s Democrats into adopting an extreme southern rights stance. But with the passage of the Compromise of 1850, which balanced California’s admission with a number of other provisions including a law facilitating the recovery of slaves who had fled into the free states, pro-Compromise Democrats formed a coalition with the Whigs and trounced Yancey’s southern rights candidates in the state elections of 1851. In the presidential election of 1852, the Yanceyites ran their own candidates for president and vice-president—George M. Troup of Georgia and John A. Quitman of Mississippi, respectively—against both the Democratic and the Whig nominees. They received just 4.6 percent of the poll and carried only Barbour and Lowndes Counties. It is clear, in short, that as late as the early 1850s, the Yanceyites still had the backing of only a tiny handful of Alabama voters. The developments that would lead the state to secession turned on the dissolution of the Whig Party and the rise of Yancey’s faction among the Democrats following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

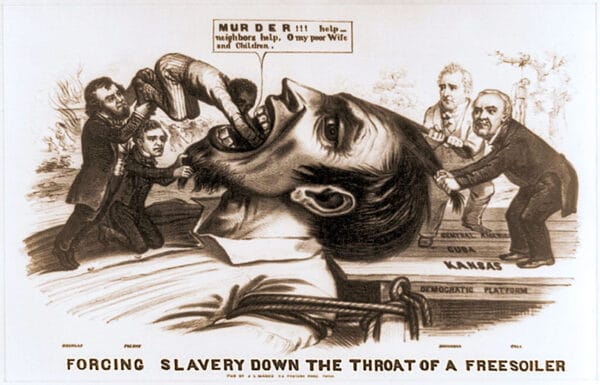

Anti-Slavery Cartoon, 1856

The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed voters in these new territories to decide for themselves whether slavery would be legal in them, an arrangement known as popular sovereignty. The opening of these territories to the possibility of slavery, which had been prohibited there by the Missouri Compromise of 1820, was widely seen by anti-slavery northerners as a part of a southern plot to extend slavery throughout the nation, the so-called Slave Power Conspiracy. Anti-slavery northern Whigs, believing that their membership in an intersectional party had prevented them from taking a sufficiently strong stand against slavery’s expansion, withdrew from the party and formed the new Republican Party, dedicated to prohibiting the introduction of slavery into every territory. The Whig Party as a national institution then disintegrated. Most southern Whigs, including Alabama’s, initially took refuge in the Know-Nothing Party. But that party’s virulently anti-Catholic doctrines alienated more moderate Whigs in Alabama as elsewhere. The Know-Nothing presidential candidate in 1856, Millard Fillmore, took only 38 percent of Alabama’s vote, and the movement in the state then collapsed. The banner of the opposition, now a mere shadow of itself, passed to an extreme southern rights faction led by Montgomery attorney Thomas J. Judge and humorist and editor Johnson J. Hooper, who argued that pro-slavery southern Democrats were unreliable defenders of their section because their desire for national victory would inevitably lead them to soften their defense of the institution.

Anti-Slavery Cartoon, 1856

The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed voters in these new territories to decide for themselves whether slavery would be legal in them, an arrangement known as popular sovereignty. The opening of these territories to the possibility of slavery, which had been prohibited there by the Missouri Compromise of 1820, was widely seen by anti-slavery northerners as a part of a southern plot to extend slavery throughout the nation, the so-called Slave Power Conspiracy. Anti-slavery northern Whigs, believing that their membership in an intersectional party had prevented them from taking a sufficiently strong stand against slavery’s expansion, withdrew from the party and formed the new Republican Party, dedicated to prohibiting the introduction of slavery into every territory. The Whig Party as a national institution then disintegrated. Most southern Whigs, including Alabama’s, initially took refuge in the Know-Nothing Party. But that party’s virulently anti-Catholic doctrines alienated more moderate Whigs in Alabama as elsewhere. The Know-Nothing presidential candidate in 1856, Millard Fillmore, took only 38 percent of Alabama’s vote, and the movement in the state then collapsed. The banner of the opposition, now a mere shadow of itself, passed to an extreme southern rights faction led by Montgomery attorney Thomas J. Judge and humorist and editor Johnson J. Hooper, who argued that pro-slavery southern Democrats were unreliable defenders of their section because their desire for national victory would inevitably lead them to soften their defense of the institution.

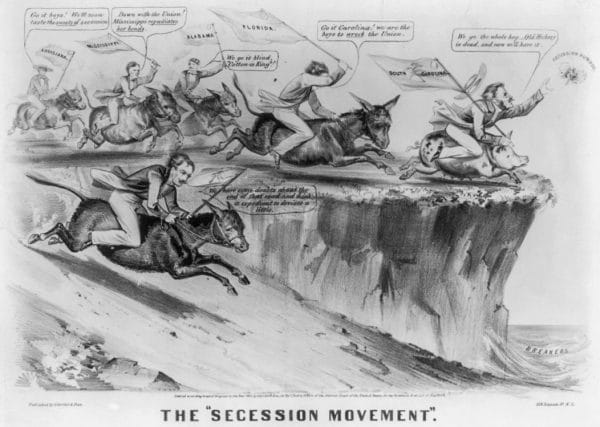

Secession Cartoon, ca. 1861

In the meantime, the increasing success of the new Republican Party in the north, with its adamant opposition to the extension of slavery into the western territories, seemed proof to more and more Alabamians of the northern intention to reduce southerners to second-class citizenship in the union. Essentially all Alabama voters, across the entire political spectrum, believed that the territories were the common property of all Americans, and therefore that all Americans should be able to go there and take their personal property, including slaves, with them. Therefore, as Republicans won more and more northern offices, Yancey’s strident condemnation of Republicans’ exclusionary doctrines increasingly made him seem to be a defender of southerners’ equal rights as American citizens. And then, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857, holding that under the Fifth Amendment, no citizen could be prohibited from taking any property, including slave property, to any territory, gave the Yanceyites’ claims clear constitutional authority and made the Republicans seem sectionalist aggressors. More moderate politicians who urged compromise now appeared to be weak appeasers, willing to sacrifice southerners’ liberties.

Secession Cartoon, ca. 1861

In the meantime, the increasing success of the new Republican Party in the north, with its adamant opposition to the extension of slavery into the western territories, seemed proof to more and more Alabamians of the northern intention to reduce southerners to second-class citizenship in the union. Essentially all Alabama voters, across the entire political spectrum, believed that the territories were the common property of all Americans, and therefore that all Americans should be able to go there and take their personal property, including slaves, with them. Therefore, as Republicans won more and more northern offices, Yancey’s strident condemnation of Republicans’ exclusionary doctrines increasingly made him seem to be a defender of southerners’ equal rights as American citizens. And then, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857, holding that under the Fifth Amendment, no citizen could be prohibited from taking any property, including slave property, to any territory, gave the Yanceyites’ claims clear constitutional authority and made the Republicans seem sectionalist aggressors. More moderate politicians who urged compromise now appeared to be weak appeasers, willing to sacrifice southerners’ liberties.

As Yancey’s inflexible defense of southern rights gained popularity, a host of young Democratic politicians flocked to his leadership, thrusting aside the old Calhounites who had earlier been his constituency. Men such as J. L. M. Curry of Talladega, Edward C. Bullock and the brothers Eli Sims Shorter and John Gill Shorter of Eufaula, Cullen A. Battle of Tuskegee, Hilary A. Herbert of Greenville, and William C. Oates of Abbeville embraced Yancey’s cause. These young and ambitious attorneys were eager to prove to the voters that they were firm defenders of the rights of Alabamians, and thus to advance their nascent political careers.

With this substantial new support, Yancey began to seek to replace Sen. Benjamin Fitzpatrick as the principal leader of the state’s Democrats. At the state party convention in January 1860, Yancey’s forces had a narrow majority and managed to push through a resolution instructing the state’s delegates to the Democratic national convention in Charleston to walk out if the convention failed to endorse the principles of the Dred Scott decision in its platform. When the Alabamians eventually did withdraw, followed by other lower-South delegations, the rift produced two separate Democratic presidential nominations: Sen. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois became the candidate of the popular sovereignty wing of the party and Vice-Pres. John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky the candidate of the Dred Scott wing that represented southern interests. Douglas’s convention offered its vice-presidential nomination to Fitzpatrick, but he was so frightened of Yancey’s emerging power in Alabama that he declined and endorsed Breckinridge.

Andrew Barry Moore

In the election, Breckinridge carried Alabama easily, with 54 percent of the poll; he lost only ten of the state’s counties. This result further strengthened Yancey’s influence among Alabama Democrats. Douglas received a mere 15 percent of the state’s vote. Whig leaders tried to rally their dispirited forces behind the candidacy of Sen. John Bell of Tennessee, but Bell managed to take just 31 percent of the poll. The Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln, whose party did not exist in Alabama or most of the South and who consequently was not a candidate there, carried every free state, thus finally providing southerners with unarguable proof that the northern majority was determined to deny their constitutional right to settle in the territories with their slaves. Because Alabama’s 1859 legislature had adopted a resolution requiring a referendum to elect delegates to a secession convention if a Republican won the presidency, Gov. Andrew B. Moore therefore issued a proclamation setting the referendum for December 24, 1860.

Andrew Barry Moore

In the election, Breckinridge carried Alabama easily, with 54 percent of the poll; he lost only ten of the state’s counties. This result further strengthened Yancey’s influence among Alabama Democrats. Douglas received a mere 15 percent of the state’s vote. Whig leaders tried to rally their dispirited forces behind the candidacy of Sen. John Bell of Tennessee, but Bell managed to take just 31 percent of the poll. The Republican nominee, Abraham Lincoln, whose party did not exist in Alabama or most of the South and who consequently was not a candidate there, carried every free state, thus finally providing southerners with unarguable proof that the northern majority was determined to deny their constitutional right to settle in the territories with their slaves. Because Alabama’s 1859 legislature had adopted a resolution requiring a referendum to elect delegates to a secession convention if a Republican won the presidency, Gov. Andrew B. Moore therefore issued a proclamation setting the referendum for December 24, 1860.

Adopting the motto “Equality In the Union, or Independence Out of It,” the Yanceyites plunged into the referendum campaign. The nationalist Whigs, disheartened by Bell’s poor showing and intimidated by the popular enthusiasm in south Alabama for Yancey’s defiant posture, did not mount any formal opposition, and many of them, particularly in the southern counties, did not vote; the total turnout fell from more than 90,000 in the presidential election in November to fewer than 67,000 in the December referendum. The southern rights opposition element of Judge and Hooper supported the Yanceyites. Fitzpatrick recognized that the referendum was his last chance to maintain his Democratic Party leadership and denounced Yancey’s support for immediate, separate state secession as rash and dangerous. He instead urged Alabamians to secede only in cooperation with the other southern states. His followers forged an alliance with the small number of genuine Unionists, and they ran so-called cooperationist tickets, opposed to separate state action, throughout most of the state. The referendum in effect became a contest between the Fitzpatrick and Yancey wings of the Democrats. The Whigs’ merger with the Unionist Democrats in 1851 had represented the crucial element in the defeat of the southern rights movement then, and now the abstention of their nationalist wing and the endorsement of the Yanceyites by their southern rights wing constituted the essential factor in determining the outcome of the referendum.

Yancey’s followers carried every county in south Alabama except Conecuh County, and Fitzpatrick’s took every county in north Alabama except Calhoun County. Supporters of immediate secession won 53 seats and cooperationists won 47. Probably the most revealing statistic about the delegates is the following: Cooperationists were a majority among delegates whose occupation was agriculture and also among those who were neither farmers nor lawyers, whereas the delegates who were lawyers were immediate secessionists by two to one. This circumstance reflects the number of young attorneys who had affiliated with Yancey’s faction in the hope of furthering their political ambitions.

The convention met on January 7 and elected the Yanceyite attorney William M. Brooks of Perry County as its president. South Carolina had already seceded by the time the convention met, and during the subsequent four days of debate, Mississippi and Florida did so as well. As a result, by the time of the final vote on the Ordinance of Secession on January 11, eight cooperationists believed that the cooperative southern action for which they had campaigned had effectively been achieved and so were willing to vote with the immediate secessionists. The Ordinance was adopted 61 to 39, and Alabama joined other southern states in leaving the Union.

Further Reading

- Barney, William L. The Secessionist Impulse: Alabama and Mississippi in 1860. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

- Denman, Clarence Phillips. The Secession Movement in Alabama. Montgomery: Alabama Department of Archives and History, 1933.

- Dorman, Lewy. Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 through 1860. Montgomery: Alabama Department of Archives and History, 1935.

- Smith, William R. The History and Debates of the Convention of the People of Alabama Begun and Held in the City of Montgomery on the Seventh Day of January, 1861. Montgomery: White, Pfister and Co., 1861.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.