Rube Burrow

Like the more famous Jesse James, outlaw and Lamar County native Rube Burrow (ca. 1856-1890) headed a gang of train robbers that included his younger brother Jim and that made off with thousands of dollars. Although there is little hard evidence to support them, a number of legends have grown up around Burrow as the “Alabama Robin Hood” because he allegedly never robbed the poor. The vast majority of his thefts targeted the U.S. Postal Service and rail companies. It is certain, however, that Burrow shot and killed at least one man.

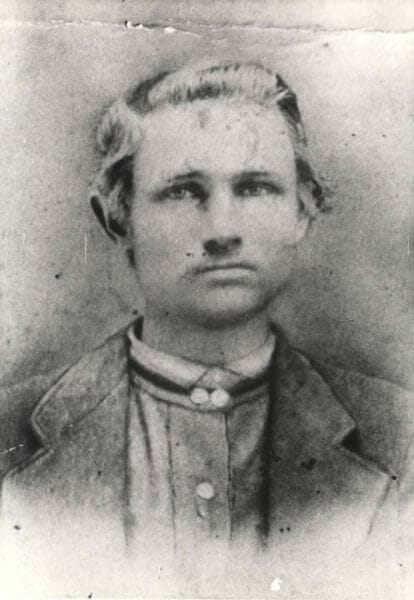

Rube Burrow

Reuben Houston Burrow (also known as Rube Burrows) was born in Lamar County, near the town of Sulligent, on December 11, probably in 1856, on the farm of his parents, Allen and Mary Caroline Terry Burrow. Some sources list his birth year as 1854, and his tombstone says 1855. Burrow was one of ten children, and their mother was known in the area as Dame Burrow, a faith healer and “witch.” As boys, Rube and his brother Jim (1858-1888) became inspired by tales of outlaw Jesse James and his gang. According to some accounts, Burrow donned a mask and robbed a neighbor at gunpoint at the age of 15, but his father recognized him and forced him to return the money. In fall 1872, he moved to Stephenville, Texas, to work as a hand on his uncle Joel Burrow’s cattle ranch. Three years later, Rube Burrow married Virginia Alvison, daughter of prominent Wise County rancher H. B. Alvison; the couple would have two children. Burrow’s brother Jim joined him in Texas in 1876.

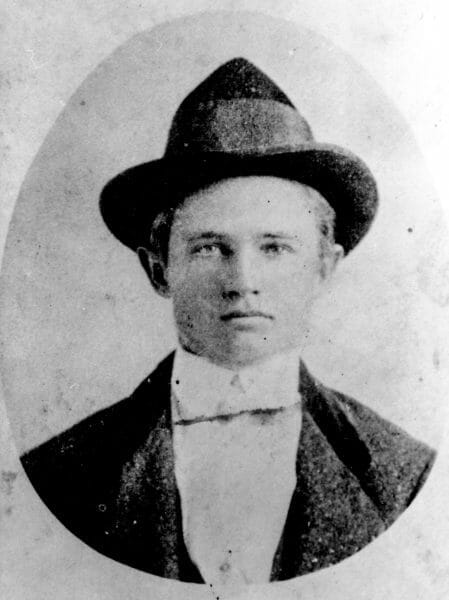

Rube Burrow

Reuben Houston Burrow (also known as Rube Burrows) was born in Lamar County, near the town of Sulligent, on December 11, probably in 1856, on the farm of his parents, Allen and Mary Caroline Terry Burrow. Some sources list his birth year as 1854, and his tombstone says 1855. Burrow was one of ten children, and their mother was known in the area as Dame Burrow, a faith healer and “witch.” As boys, Rube and his brother Jim (1858-1888) became inspired by tales of outlaw Jesse James and his gang. According to some accounts, Burrow donned a mask and robbed a neighbor at gunpoint at the age of 15, but his father recognized him and forced him to return the money. In fall 1872, he moved to Stephenville, Texas, to work as a hand on his uncle Joel Burrow’s cattle ranch. Three years later, Rube Burrow married Virginia Alvison, daughter of prominent Wise County rancher H. B. Alvison; the couple would have two children. Burrow’s brother Jim joined him in Texas in 1876.

Burrow purchased land soon after his marriage and established his own farm. In 1880, Virginia Burrow died of yellow fever, and Burrow returned briefly to Alabama to leave the children with his mother. He returned to Texas and resumed his life as a farmer and cowhand; in 1884, he married Adeline Hoover of Erath County. Having always been athletic, Burrow quickly gained a reputation as an excellent rider and marksman and was soon leading a band of cowboys, including future outlaw cohorts Henderson Bromley and Nep Thornton.

In late 1886, Burrow’s farm failed and he separated from his second wife. Perhaps inspired by the recent exploits of Texas train robber Sam Bass and his gang, he formed an outlaw gang with Jim, Thornton, and Bromley. The gang first headed to what was at the time Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) but met with little success. In December, the gang robbed $300 from a train on the Fort Worth & Denver line at Bellevue, Texas, on their way home to Erath County. On January 23, 1887, the gang robbed a train on the Texas & Pacific line at Gordon, Texas, netting several thousand dollars.

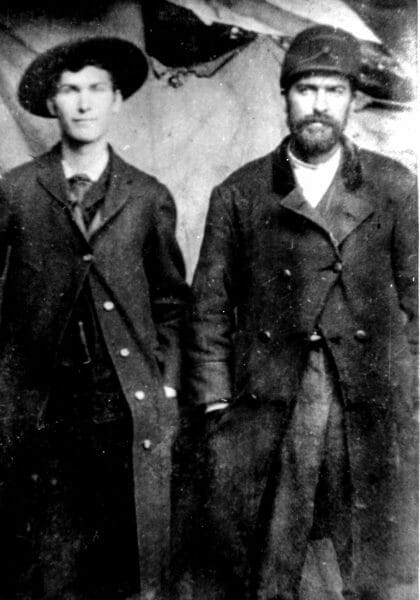

Burrow, Rube

After escaping into the Texas hill country, the men returned home to Alexander and resumed their normal lives to avoid attention from the authorities. In March, the Burrow brothers purchased land in Erath County and earned their living as cattlemen and farmers until early May. Burrow then raised his former gang, augmented by ranch hand William Brock, and made plans to rob the train at Gordon again; they were forced to turn back by high waters in the Brazos River. On June 4, 1887, they robbed a train at the town of Ben Brook (now Benbrook), Texas, and made off with more than $2,000. After returning for a time to their farms again to avoid suspicion, they robbed the same train in Ben Brook in September, netting more than $2,500. In November, Burrow and his brother travelled to Lamar County to visit their family.

Burrow, Rube

After escaping into the Texas hill country, the men returned home to Alexander and resumed their normal lives to avoid attention from the authorities. In March, the Burrow brothers purchased land in Erath County and earned their living as cattlemen and farmers until early May. Burrow then raised his former gang, augmented by ranch hand William Brock, and made plans to rob the train at Gordon again; they were forced to turn back by high waters in the Brazos River. On June 4, 1887, they robbed a train at the town of Ben Brook (now Benbrook), Texas, and made off with more than $2,000. After returning for a time to their farms again to avoid suspicion, they robbed the same train in Ben Brook in September, netting more than $2,500. In November, Burrow and his brother travelled to Lamar County to visit their family.

In December, while still in Alabama, the brothers appear to have met up with William Brock and robbed the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas Railroad line in Genoa, Arkansas. On December 9, they made off with the monies collected for the Illinois lottery, raising the attention of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, a private security and investigative organization often employed by railroad companies. After a brief skirmish with a sheriff and his men outside Texarkana, Arkansas, the Burrow brothers returned to Lamar County, and William Brock headed back to Texas. There, Pinkerton agents traced him via coats the men had discarded near the tracks after the robbery and arrested him on December 31, 1887, outside the town of Dublin, Texas; he soon implicated the Burrow brothers and told the detectives where they were.

In early January 1888, Pinkerton assistant superintendent John McGinn raised a party in Lamar County to arrest Burrow at his house but lost him after a series of errors about which house was the right one. That night, the brothers boarded a Louisville and Nashville (L&N) train just south of Birmingham and headed south. A conductor on the train recognized them from police flyers, wired ahead to the station in Montgomery (where the brothers intended to get off), and arranged for the police to meet the train when it stopped.

The police attempted to lure them to the jail when they left the train by posing as railroad workers and offering to find them lodging; however, the Burrows realized the ruse and fought with the police. Rube escaped after shooting an officer, but Jim was captured. Burrow escaped the subsequent manhunt, stole a horse, and headed south, where his pursuers lost his trail. Burrow then turned back north and returned to Lamar County to seek news of his brother, who was now imprisoned in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In March 1888, Burrow partnered with Leonard. C. Brock (also known as Lewis Waldrip), who had worked with Burrow as a ranch hand in Texas, and convinced him to adopt the name of notorious Texas train robber “Joe Jackson” to strike fear in pursuers by convincing them that he had taken up with an even more dangerous outlaw. The men set out from Lamar County and travelled south through Columbus, Mississippi, before heading east and seeking shelter in a logging camp in the backwoods of Baldwin County, Alabama. In May, Burrow and Brock headed back north to Lamar County, hoping that their pursuers had given up interest in the area.

After reaching home, Burrow began working on a plan to free his brother from jail. In August, Burrow and Brock headed for Little Rock after learning that Jim Burrow would be moved to Texarkana. The men could not intercept Burrow’s train, however. After arriving in Texarkana, Jim Burrow wrote home to his family to send funds for a lawyer and voiced his belief that he would be acquitted of all charges when his trial took place the following March. In late September, however, he fell ill, and he died on October 5, 1888, most likely of tuberculosis.

Having failed in their rescue attempt, Burrow and Brock headed back to Lamar County, taking back roads to avoid detection. On December 15, 1888, they robbed a train in Duck Hill, Mississippi, and shot and killed a passenger who attempted to thwart the robbery. His murder raised alarms in the national press and among the railroad companies, who feared a loss in revenue if the safety of train travel came under question. Because the description of the shooter also matched that of train robber Eugene Bunch, the Pinkertons pursued him rather than Burrow. Burrow and his men returned safely to Lamar County, where Burrow’s extended family provided the men with supplies and safe haven throughout the spring of 1889 and kept watch for detectives and bounty hunters.

All went well for Burrow and Brock until the first week of July, when Burrow shot the local postmaster for refusing to hand over a suspicious package (containing a wig and false mustache). In the aftermath, three of Burrow’s relatives were jailed briefly for aiding the outlaws. Safe among Burrow’s network of relatives, however, the men remained in the area until September.

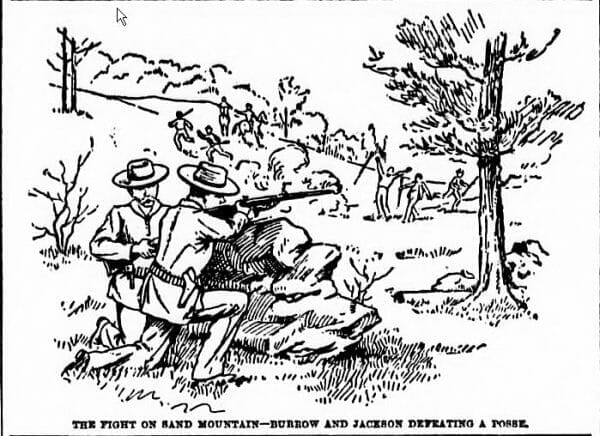

Rube Barrow Cartoon

During the first week of September, Burrow and Brock, now joined by Burrow’s cousin Rube Smith, set out to the southwest in search of a likely site for their next train robbery. They robbed the mail car and express car of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad line at Buckatunna, Mississippi, of several thousand dollars and then returned to Lamar County once again. By November, however, the police and bounty hunter presence were making Burrow nervous. With the help of his father, Burrow and Brock purchased an oxcart and travelled to Flomaton, Escambia County, arriving on December 14, 1889. Several days later, Rube Smith and associate James McClung were captured at Amory, Mississippi, after attempting to rob a train. The men were imprisoned in Aberdeen, Mississippi.

Rube Barrow Cartoon

During the first week of September, Burrow and Brock, now joined by Burrow’s cousin Rube Smith, set out to the southwest in search of a likely site for their next train robbery. They robbed the mail car and express car of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad line at Buckatunna, Mississippi, of several thousand dollars and then returned to Lamar County once again. By November, however, the police and bounty hunter presence were making Burrow nervous. With the help of his father, Burrow and Brock purchased an oxcart and travelled to Flomaton, Escambia County, arriving on December 14, 1889. Several days later, Rube Smith and associate James McClung were captured at Amory, Mississippi, after attempting to rob a train. The men were imprisoned in Aberdeen, Mississippi.

For the next two months, detectives searched all over south Alabama for Burrow and Brock. In early February, a detective questioned a ferryman at a crossing near Milton, Florida, and learned that Burrow and his companion had split up after reaching Flomaton and that Burrow was working at a logging camp in Santa Rosa County, Florida, across the Yellow River. Once again, Burrow somehow detected an ambush on his grain-hauling route and escaped into the woods. Brock, however. was captured on a train at the Fernbank Station in Lamar County, where he had travelled in the hope of finding Burrow. After his arrest, Brock was taken to prison in Memphis, Tennessee, to await trial.

On September 1, 1890, word reached detectives of the robbery of a L&N train at Pollard that apparently Burrow had pulled off singlehandedly. Detectives traced him back to the camp in Santa Rosa County in Florida and took up watch in the home of the family that Burrow had been staying with. The family got word to Burrow, however, and he fled the area and lived in the backwoods. Outside Demopolis, in Marengo County, Burrow was recognized by a man who tricked Burrow into stopping at a friend’s house for dinner and who, with the help of the friend, captured Burrow and held him until detectives arrived. Burrow was then bound to a horse and taken to Linden, the Marengo County seat.

On the morning of October 9, 1890, Burrow had not been in custody for half a day when he attempted escape by getting the police to untie his hands so he could eat, then pulling a hidden pistol on them. He made his way to the front of the jail, where he engaged in a shoot-out with local merchant Jefferson Davis Carter. Burrow fired all of the bullets in his pistol, striking Carter once in the abdomen, before Carter shot Burrow in the chest as he turned to run, killing him instantly. Rube Burrow’s body was shipped by train back to Lamar County, making several stops along the way so that the public could see the body of the famous train robber. His weapons were also put on display in Memphis, Tennessee, and attracted huge crowds. When his body reached Sulligent, it was collected by his father, and Burrow was buried in Fellowship Cemetery. Exactly one month later, former gang member William Brock leapt to his death from the top floor of the Brock Penitentiary in Jackson, Tennessee, after receiving a life sentence.

Further Reading

- Agee, George W. Rube Burrow, King of Outlaws, and His Band of Train Robbers. An Accurate and Faithful History of Their Exploits and Adventures. Chicago: Henneberry Company, 1890. [See Related Links]

- Hoole, William Stanley. The Saga of Rube Burrow, King of American Train Robbers, and His Band of Outlaws. Tuscaloosa: Confederate Publishing Company, 1981.