United Mine Workers in Alabama

Organizations representing miners’ interests first appeared in the Birmingham District in the 1870s, created with the assistance of the Greenback-Labor Party. Later, many miners joined the Knights of Labor but ultimately found more success improving working conditions and wages under the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and its subsidiary, the United Mine Workers of Alabama, District 20. These organizations were successful in recruiting and meeting workers’ needs when demand for coal was high, generally during periods of international conflict, but their influence faded as racism divided workers and the demand for Birmingham’s coal slowed in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Early workers’ organizations reflected the independence of miners, who worked as subcontractors and received compensation based on the amount of coal that they produced. These organizations hired their own labor (often African Americans), provided tools and supplies, and largely controlled life in the mines. Concerned about their inability to obtain bank loans and the high cost of railroad freight, miners joined with farmers in the Greenbacker movement to form the Greenbacker-Labor Party in the late 1870s. At times, such early organizations staged “strikes,” but they never functioned as labor unions per se.

By the mid-1880s, the Greenbacker movement in Alabama had disappeared. In the coal fields, however, the larger and better structured Knights of Labor filled the organizational vacuum, establishing “assemblies” across the Birmingham District in beginning in 1879. (The Birmingham Mineral District encompassed portions of Jefferson, Shelby, Bibb, Tuscaloosa, and Walker Counties.) Miners found the Knights appealing and joined in substantial numbers; most mining camps in the district had Knights assemblies by the mid-1880s. Although the Knights officially opposed strikes, Birmingham District assemblies of miners staged the first major strike in the late 1880s. In keeping with the production-oriented mentality of miners, the strikers demanded and won a return to compensation based on their production and control over weighing the coal.

Although the Knights met with some success, the organization did not survive an economic recession in the Birmingham District in the mid-1880s. A few years later, leaders of the newly created UMWA decided to extend the organization south, and, in April 1890, John L. Conley created District 20 of the UMWA in Alabama. Conley and Patrick McBryde, a member of the union’s National Executive Board, established locals across District 20. In the fall of 1890, the UMWA went on strike after operators refused to increase tonnage rates. The failure of the strike, combined with declining demand for coal, severely hampered organizing efforts, and the UMWA retreated for a few years.

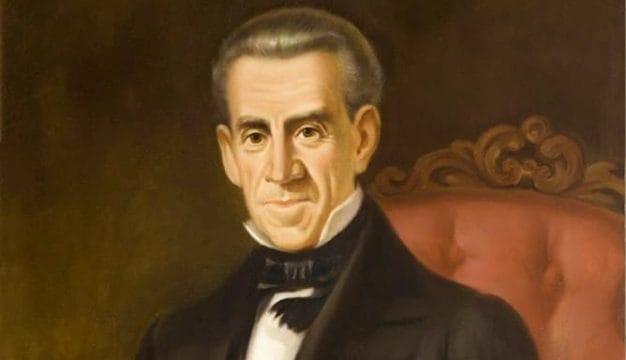

After the UMWA backed away from organizing in the area, miners in Alabama created the unaffiliated, independent United Mine Workers of Alabama (UMW-Alabama) around 1893. A deep economic depression had created enormous hardships for miners and their families as mine operators, such as Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company and the DeBardeleben Coal and Iron Company, faced with a sharp decline in demand, reduced the tonnage rates paid to miners. Tonnage rates had always been based on the market price for coal, so the miners did not object to a reduction. They did, however, challenge a 22.5-percent salary decrease that operators sought to impose. The dispute over compensation and miner hostility toward the convict-lease system sparked the largest strike in the district’s history, the so-called Great Strike of 1894, involving as many as 9,000 miners. Opposed by operators led by Henry F. DeBardeleben, the miners had considerable support in the community, but the depressed state of the coal market, a surplus of willing workers, and intervention by the state (with Gov. Thomas Goode Jones calling up the state militia and declaring martial law) undermined the effectiveness of the strike and caused it to fail.

The coal market improved with the increased demand created by the Spanish-American War. Recognizing an opportunity, the UMWA reestablished its District 20 organization in May 1898 and soon had more than 1,000 members. (It would boast 15 local organizations and 2,300 members by the end of the year and 95 locals and 14,000 members by 1903.) Operators signed contracts with the union that included improvements in compensation and increased miner supervision of weighing. After the Spanish-American War, the influence of the UMWA waxed and waned depending on the market, maintaining a tenuous presence in the district. It barely survived several strikes in the early 1900s, most notably the violent 1908 strike involving some 20,000 miners opposing an attempt to lower wages. It was broken with the aid of militia troops led by Gov. Braxton Bragg Comer and resulted in operators forming the Alabama Coal Operators Association (ACOA) to coordinate anti-union efforts.

During World War I, demand for coal again increased sharply, and the UMWA took advantage of the situation to again expand its influence. In July 1917, it held its first convention in nine years. By that time, the federal government had begun to intervene in labor disputes that threatened the production of commodities such as coal that were essential to the war effort. Thus, when the miners threatened a strike in August 1917, the U.S. Fuel Administration helped broker an agreement between the UMWA and the operators. Under the agreement, miners secured semi-monthly pay days, a checkweighman of their choosing, reinstatement of miners dismissed for union activity, and an eight-hour workday. This government-assisted success sparked a spurt in District 20 membership with 128 locals and 23,000 members.

Union expansion during World War I was based on exceptional, temporary conditions. Thus, when the war ended, the demand for coal declined, and the government withdrew from the coal fields. The UMWA, ignoring these conditions that did not bode well for labor organizations, decided to demand a pay increase that had been delayed because of the war. At the same time, the ACOA was preparing to roll back the union’s gains since 1916. So, when the union issued its demand for a wage increase, the operators, now free of the tight labor market conditions under which the union had flourished, refused, and the UMWA went on strike in 1920 and 1921. Racial divisions among miners, hostility in the community, the ability of the operators to hire replacement miners, and state troops sent in by Gov. Thomas Kilby proved too much for the strikers to overcome. The ACOA defeated the strike and ushered in the return of the open shop to their mines.

The UMWA reemerged during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Encouraged by the sympathetic attitude of federal officials toward organized labor and the aggressive leadership of John L. Lewis at the national level, Walter Jones, an African American organizer from Montevallo, and others began to revive moribund locals and create new ones in 1932 and 1933. They exploited local general discontent over the effects of the Great Depression and particular grievances over poor conditions in the mines to recruit thousands of new members. The operators mounted some resistance to the organizing drive in 1933, but by 1934, 90 percent of operators had signed union contracts that provided a number of improvements for miners, including wage increases.

Officially the UMWA was a “biracial” union, as it had been throughout its history. In practice, however, and despite the presence of a token black officer or two, the union was dominated by and run by whites. Yet even the limited influence of African Americans in the union was troubling to white members and members of other unions in the Birmingham District. This racial tension was central to the expulsion of the UMWA from the Alabama Federation of Labor in 1936. Large numbers of white workers then began joining the whites-only Brotherhood of Mine Workers of Captive Mines. The UMWA remained a Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) affiliate until it split with the CIO over allegations of Communist influence under its president, Philip Murray.

World War II brought another surge in economic growth to the Birmingham District. Demand for labor grew accordingly, and miners attempted to use their market power to address issues arising from the inflationary pressures of the period. With housing and food prices rising, rank-and-file miners sought increased wages. Leaders of the UMWA, however, had made a wartime no-strike pledge. When the rank and file went on strike several times between April and November 1943, the local press was sharply critical of the miners and their leaders for disrupting the supply of coal critical to the war effort. In response to the strike, Gov. Chauncey Sparks threatened to remove critical occupation draft deferments for strikers. The Alabama legislature passed in 1943 the Bradford Act, which effectively ended the closed shop, in which employers pledged to hire only unionized workers, in Alabama. Nevertheless, miners continued to strike across the district, often without the blessing of union leaders. Finally, Pres. Franklin Roosevelt ordered the mines returned to government control. The UMWA won a small pay increase, but these limited gains came at great cost in terms of local support.

Generally, the UMWA declined after World War II, along with the local market for Alabama coal. Coal mining in Alabama had always been tied to the fortunes of the Birmingham steel industry, and by the 1960s, the steel industry was struggling. The union worked for improvements in the health and pension systems and tried to maintain high wages. But with the industry declining in the district, operators could find plenty of replacements for striking workers and successfully resisted union initiatives. Moreover, the union faced severe internal problems as white members, feeling threatened by the growing civil rights movement, joined the Ku Klux Klan despite a union prohibition on such activities. Many white members who did not associate with organized resistance to African American aspirations, however, still expressed their hostility toward black equality by supporting politicians such as Eugene “Bull” Connor and George Wallace, who promised to defend segregation and white supremacy. Whereas the racial divisions within the UMWA certainly undermined the organization, it was ultimately the decline of the industry, and the transformation of the Birmingham District into a medical and financial center, that largely destroyed the union’s relevance in the region.

Additional Resources

Brown, Edwin L. and Colin J. Davis. It is Union and Liberty: Alabama Coal Miners and the UMW. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

Kelly, Brian. Race, Class, and Power in the Alabama Coalfields: 1908-21. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001.