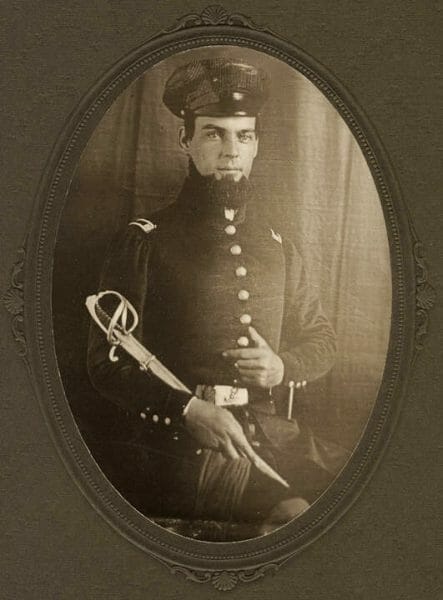

John Gorman Barr

John Gorman Barr

Humorist John Gorman Barr (1823-1858) wrote in the Old Southwest tradition of his contemporaries and fellow Alabamians, Johnson Jones Hooper and Joseph Glover Baldwin. Although Barr enjoyed only a brief writing career, his humorous sketches and unique characterizations are ranked by critics as among the best portrayals in the genre of Old Southwestern Humor. Barr’s stories of frontier life are set in Alabama, mostly in Tuscaloosa, and stand out from those of most other Old Southwestern humorists in that many of his characters are based on real places and on actual citizens of Tuscaloosa. Although upper-class planters, lawyers, merchants, and doctors appear in the stories, the focus is mainly on common people, such as ordinary laborers, small businessmen, immigrants, and women; others concern Ned Berry, a free black man and a successful wagoner.

John Gorman Barr

Humorist John Gorman Barr (1823-1858) wrote in the Old Southwest tradition of his contemporaries and fellow Alabamians, Johnson Jones Hooper and Joseph Glover Baldwin. Although Barr enjoyed only a brief writing career, his humorous sketches and unique characterizations are ranked by critics as among the best portrayals in the genre of Old Southwestern Humor. Barr’s stories of frontier life are set in Alabama, mostly in Tuscaloosa, and stand out from those of most other Old Southwestern humorists in that many of his characters are based on real places and on actual citizens of Tuscaloosa. Although upper-class planters, lawyers, merchants, and doctors appear in the stories, the focus is mainly on common people, such as ordinary laborers, small businessmen, immigrants, and women; others concern Ned Berry, a free black man and a successful wagoner.

Barr was born in Milton, North Carolina, on November 22, 1823, to Scottish immigrants Thomas Barr and Mary Jane Gorman Barr. Shortly after Barr’s birth, the family moved to Raleigh, North Carolina, where Thomas Barr died in 1826. Nine years later, in 1835, Mary Jane Gorman Barr moved her two children, John Gorman and Mary Margerette, to Tuscaloosa, where she died within the year. Educated by his mother until her death, Barr apprenticed himself to a printing office, where he attracted the attention of merchant David Boyd, who funded his education at the University of Alabama. After graduating in 1841 with honors and receiving his master’s degree in 1842, Barr was hired by the university as a math tutor. Soon after, he applied for a position as the school’s librarian but was denied the post in the aftermath of a conflict between the president, Basil Manly, and the secretary of the faculty, Frederick A. P. Barnard (later president of what is now Columbia University).

During this time, he also studied law and in 1845 was admitted to the bar. In 1847, he ran unsuccessfully for the Alabama House of Representatives and then organized a group of volunteers to fight in the Mexican War. Although he never saw action, he rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Upon his return to Tuscaloosa in 1848, he resumed his law practice and became managing editor of the Tuscaloosa Observer. During this period, Barr also began publishing his works of fiction. His first story, “Salted Him, or An Auctioneer Doing All the Bidding,” was published in October 1855 in the weekly newspaper The Spirit of the Times, which was published in New York City and read largely by upper-class outdoors and sports enthusiasts. Barr published 11 other stories over the next two years and established a national reputation as a humorist. His last story, “Misplaced Confidence; or, Bilking a Boniface,” was published in The Spirit of the Times in 1857.

Like most other Old Southwestern humorists, Barr attempted to create a mythologized South in his works. Unlike other such writers, who were generally Whigs and who focused on the lives of aristocrats, Barr, a Democrat, focused his characterizations on poor whites of the working classes and farming families. Although he wrote in a common vernacular, he did not include the poor-white dialect that was a mainstay of Old Southwestern humorists; he also avoided derogatory comments about poor whites, the social class from which he came. He occasionally employed an Irish dialect, but he never derided his Irish characters. As was typical of the times, aristocrats, Blacks, and Yankees were the objects of humiliations and cruelties and the subjects of frontier eccentricities in his stories. Barr’s narratives are notable for their humor and for providing a microcosm of antebellum life, which he saw in an increasingly romanticized light over the brief course of his writing career.

Elaborate practical jokes lie at the heart of some of Barr’s best pieces. Two works that have been anthologized in collections of twentieth-century literature are “John Bealle’s Accident—or, How the Widow Dudu Treated Insanity” and “New York Drummer’s Ride to Greensboro.” In the latter, a self-important but very weary New York traveling salesman is, with the aid of periodic doses of liquor, made to believe that he has travelled from Tuscaloosa to Greensboro when in fact he has been the overnight occupant of a stationary, horseless stagecoach.

During the 1856 presidential election, Barr supported victor James Buchanan and ran the following year for the U.S. Congress. After agreeing to withdraw from the race for the sake of party unity and as a reward for his support of Buchanan, he was appointed to serve in the American consulate in Melbourne, Australia, the following year. After touring Europe, he died of heatstroke en route to Australia on May 18, 1858, and was buried in the Indian Ocean.

Further Reading

- Beidler, Philip D., ed. The Art of Fiction in the Heart of Dixie. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1986.

- Hoole, W. Stanley. “John Gorman Barr: Forgotten Alabama Humorist.” Alabama Review 4 (April 1951): 83-116.

- Hubbs, G. Ward, ed. Rowdy Tales from Early Alabama: The Humor of John Gorman Barr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981.

- ———. “Letters from John Gorman Barr.” Alabama Review 36 (October 1985): 271-84.