States' Rights

The question of which powers belong to the states and which powers belong to the federal government, and how to resolve conflicts between the two levels of government, has been a theme throughout much of Alabama’s history. To an extent, this debate is a result of the nature of the system of government in the United States as well as the interpretation of the separation of powers outlined in the Constitution, with some powers delegated to the federal government, and others retained by the states.

States’ rights is a school of constitutional interpretation that emphasizes the sovereignty of the states (or the people of the states) and limitations on federal powers. The Articles of Confederation declared that each state that ratified the document retained its sovereignty and independence and that every power or right not delegated to the United States collectively was retained by the states. Under the subsequent Constitution, elements of state sovereignty were retained. During the ratification debate, opponents of federalism argued that the Constitution would allow for an open-ended increase in the powers of the federal government. Advocates of federalism, such as James Madison and James Wilson, countered that the federal government would be strictly limited to those powers expressly delegated to it by the Constitution.

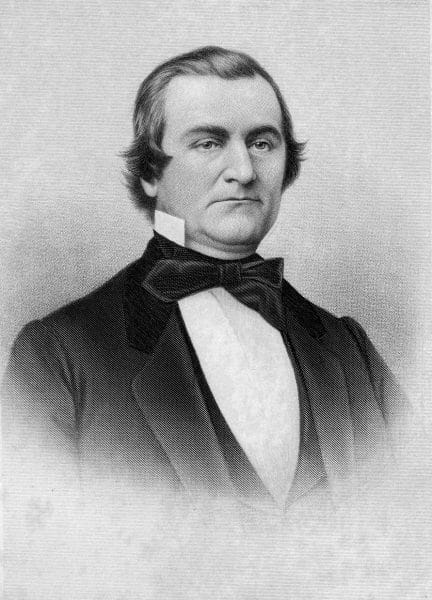

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

During the early nineteenth century, as debates over actions by northern interests against southern industry and economics and the institution of slavery developed, the states’ rights position came increasingly to be perceived as a peculiarly southern view of the Constitution. As the sectional crisis deepened, the states’ rights position increasingly became the rallying cry for political leaders. When northern states took a majority of the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate, Alabamians increasingly believed that representation of their views in the governing process would follow only from strict interpretation of the Constitution and its enumeration of federal powers. In a speech in Washington, D.C., on September 21, 1860, Alabama politician and orator William Lowndes Yancey, an outspoken proponent of states’ rights, pointed out that the majority held by northern states protected their views. The South, on the other hand, saw the limits on federal powers as a shield for the South. Only a strict interpretation of federal powers and an expansive interpretation of states’ rights could protect the minority South.

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

During the early nineteenth century, as debates over actions by northern interests against southern industry and economics and the institution of slavery developed, the states’ rights position came increasingly to be perceived as a peculiarly southern view of the Constitution. As the sectional crisis deepened, the states’ rights position increasingly became the rallying cry for political leaders. When northern states took a majority of the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate, Alabamians increasingly believed that representation of their views in the governing process would follow only from strict interpretation of the Constitution and its enumeration of federal powers. In a speech in Washington, D.C., on September 21, 1860, Alabama politician and orator William Lowndes Yancey, an outspoken proponent of states’ rights, pointed out that the majority held by northern states protected their views. The South, on the other hand, saw the limits on federal powers as a shield for the South. Only a strict interpretation of federal powers and an expansive interpretation of states’ rights could protect the minority South.

Ironically, the South’s uncharacteristic demand for a renewed evaluation of federal powers was the catalyst in a split in the Democratic Party and ultimately in the outbreak of the Civil War. The southern branch of the Democratic Party introduced a resolution demanding that any Democratic office holder pledge to protect slavery in the federally controlled territories. Known as the Alabama Platform because it was introduced by Yancey, the language declared that the federal government had an obligation to protect private property, including slaves, in the territories controlled by Congress. In the 1860 Democratic Party convention in Charleston, South Carolina, Democratic presidential candidate Stephen Douglas refused to embrace the slavery-protection plank. The southern state delegations, led by the Alabama delegation, left the convention, helping split the Democratic Party in the ensuing election and ensuring Abraham Lincoln’s win in the 1860 presidential election.

After the Civil War and Reconstruction, Alabama, along with other southern states, used states’ rights arguments to restore a system of white supremacy and racial segregation. After the overthrow of Republican rule in the 1870s, the “redeemed” state government enacted laws to restrict African American voting. In 1896, the Supreme Court case Plessy vs. Ferguson exposed an apparent conflict between the states’ rights enumerated in the Tenth Amendment and the

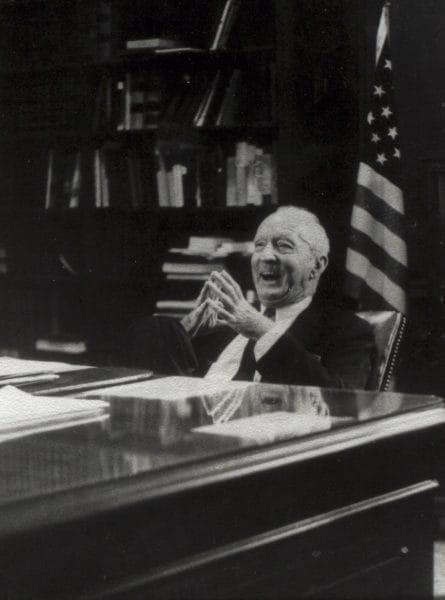

Hugo Black

“equal protection” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. Supreme Court Justice Henry Brown, writing for the majority, handed down a decision that gave state legislatures most of the decision-making powers relating to the case. In 1947, U.S. Supreme Court Justice and Alabama native Hugo Black argued for the theory of incorporation, in which the Bill of Rights, which had originally restricted only the federal government, applied to actions by state governments as well. The stage thus was set for another conflict between federal powers and states’ rights.

Hugo Black

“equal protection” provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. Supreme Court Justice Henry Brown, writing for the majority, handed down a decision that gave state legislatures most of the decision-making powers relating to the case. In 1947, U.S. Supreme Court Justice and Alabama native Hugo Black argued for the theory of incorporation, in which the Bill of Rights, which had originally restricted only the federal government, applied to actions by state governments as well. The stage thus was set for another conflict between federal powers and states’ rights.

In 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace took a states’ rights position in his attempt to prevent the admission of African American students to the University of Alabama. Alabama advocates of African American rights found no appreciable support from within the state’s dominant political culture, so they turned to help from outside the state, particularly the federal government. In the ensuing actions, the federal government used incorporation and an expansive interpretation of the commerce clause in the Constitution to overrule state laws on segregation throughout Alabama and the South, including segregation in schools and private business establishments. The term still appears on occasion in political speech, in some cases as code language indicating support of discriminatory practices or outright racism; as a result, its use is often met with skepticism or suspicion by the public at large.

Additional Resources

Frederickson, Kari A. The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Key, V. O. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1956.

Owsley, Frank L. State Rights in the Confederacy. Gloucester, Mass.: Peter Smith, 1961.