Sequoyah

Sequoyah

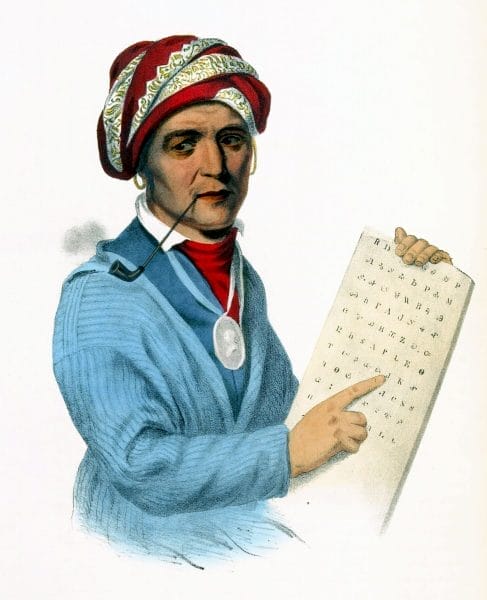

Sequoyah (also known as George Guess and George Gist) was one of the most influential men in the history of the Cherokees. In addition to leading a very active role in war and politics, his greatest legacy to the Cherokee nation was his invention of a syllabary, a written version of the Cherokee spoken language that enabled the Cherokees to record their traditions and establish a native language newspaper, among other developments. Although born in what is now Tennessee, Sequoyah lived a large portion of his life in what is present-day northeastern Alabama, even serving in the Creek War of 1813-14; much of the work on his syllabary was accomplished while he lived in the state.

Sequoyah

Sequoyah (also known as George Guess and George Gist) was one of the most influential men in the history of the Cherokees. In addition to leading a very active role in war and politics, his greatest legacy to the Cherokee nation was his invention of a syllabary, a written version of the Cherokee spoken language that enabled the Cherokees to record their traditions and establish a native language newspaper, among other developments. Although born in what is now Tennessee, Sequoyah lived a large portion of his life in what is present-day northeastern Alabama, even serving in the Creek War of 1813-14; much of the work on his syllabary was accomplished while he lived in the state.

Sequoyah was born in the Overhill Cherokee town of Tuskegee, near present-day Vonore, Tennessee, sometime around 1776. He inherited his Paint Clan membership through his Cherokee mother, Wurteh. His father was probably the white hunter-soldier Nathaniel Gist, who left the area when Sequoyah was very young. He was related to Chickamauga war chief John Watts through his mother. As a young man, Sequoyah worked on his mother’s farm raising dairy cows, breaking horses, and hunting for the deerskin trade after the family moved to Willstown in present-day DeKalb County, Alabama. Later, he became interested in metals and worked as both a silversmith and blacksmith.

Sequoyah became curious about the process of writing that he observed in English-printed books and came to believe that it would be possible to create a written form of the Cherokee language. Beginning in 1809, he experimented with pictographs but found them too daunting. He eventually arrived at a method of assigning one character or symbol to each syllable of sound in the Cherokee language. Although he could not speak, read, or write English, Sequoyah adapted some symbols from the English alphabet and assigned Cherokee syllables to them. For other syllables, he assigned symbols of his own creation.

A few years after Sequoyah began this work, the Cherokees joined the United States against the Red Stick faction of Creeks in the Creek War of 1813-14. Sequoyah enlisted as a private in the Mounted and Foot Cherokees under Capt. James McLemore in Col. Gideon Morgan’s Cherokee Regiment. He mustered into service at Turkeytown (the present-day town of Centre, Cherokee County) on October 7, 1813, for three months. On January 6, 1814, he reenlisted for a second tour of duty and was involved in a number of military actions. Fifteen days after their victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Sequoyah received an honorable discharge.

In 1815, Sequoyah married Sally Benge and diligently continued to toil on his invention, leaving the farm work to his Cherokee wife. She became angry and burned his writings. Nevertheless, the determined Sequoyah completed the syllabary in 1821 after voluntarily removing west to Indian Territory in Arkansas. He then proceeded to teach it to his young daughter and his brother-in-law.

When the 1821 Cherokee National Council met at Sauta (in present-day Jackson County), Sequoyah demonstrated the accuracy of the 86-character syllabary as an effective means of communicating the Cherokee language in written form. The Cherokee leadership approved its dissemination, and within a matter of months the Cherokee Nation became mostly literate. By 1828, the tribe established The Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper printed in both Cherokee and English. Missionaries quickly used the syllabary to translate parts of the Bible and hymns into the Cherokee language.

Although Sequoyah was never a principal chief, he was active in Cherokee politics and an influential person. He was one of the Cherokee delegates who signed the 1816 Treaty of Chickasaw Council House, which ceded most of the Cherokee claims to land in present-day north Alabama. In 1818, Sequoyah joined a group of Cherokees who volunteered to immigrate west. His syllabary now allowed the eastern and western Cherokees to communicate with one another.

Sequoyah lived the remainder of his life in Arkansas and Oklahoma, staying active in tribal politics. He served as a delegate for the western Cherokees to Washington, D.C., in 1827, in negotiations for the exchange of Arkansas Indian Territory land for land in present-day Oklahoma. During this trip, painter Charles Bird King created Sequoyah’s now famous portrait.

Sequoyah later operated a salt works in the Cherokee district of Skin Bayou (later renamed Sequoyah District) and also taught the syllabary to Cherokee students at Dwight Mission. When the eastern Cherokees were removed to Indian Territory in 1839, Sequoyah served as the president of the western Cherokees, or Old Settlers, and signed the Act of Union that reunited the two groups.

In 1842, Sequoyah, his son, and seven friends journeyed to Mexico in search of a band of Cherokees, hoping to teach them the syllabary. Three years after his departure, the Cherokee Indian Agent sent a search party, which found that Sequoyah had died in August 1843 near San Fernando of a probable respiratory infection. He was buried in an unmarked grave.

Sequoyah Caverns

For his achievements, Sequoyah has been honored in a number of ways. In 1847, the giant Sierra redwood, Sequoia gigantean, was named in his honor. Oklahoma Territory almost became the State of Sequoyah in 1905. In 1907, the state of Oklahoma chose the likeness of Sequoyah to represent its citizenry in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall. In 1936, the Oklahoma Historical Society worked with the federal Work Projects Administration to restore and preserve his home near Sallisaw. In 1961, the state of Alabama planted a redwood on the campus of the University of Alabama in Huntsville. In addition, the North Alabama Historical Association hosted a presentation by the national chairman of the Bicentennial Commemoration at the Russell Erskine Hotel. Encouraged by the Alabama congressional delegation, the U.S. Post Office issued a 19-cent stamp honoring Sequoyah as the premier stamp in its new Great American Series on December 27, 1980. Sequoyah Caverns, in Valley Head, DeKalb County, is named for Sequoyah.

Sequoyah Caverns

For his achievements, Sequoyah has been honored in a number of ways. In 1847, the giant Sierra redwood, Sequoia gigantean, was named in his honor. Oklahoma Territory almost became the State of Sequoyah in 1905. In 1907, the state of Oklahoma chose the likeness of Sequoyah to represent its citizenry in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall. In 1936, the Oklahoma Historical Society worked with the federal Work Projects Administration to restore and preserve his home near Sallisaw. In 1961, the state of Alabama planted a redwood on the campus of the University of Alabama in Huntsville. In addition, the North Alabama Historical Association hosted a presentation by the national chairman of the Bicentennial Commemoration at the Russell Erskine Hotel. Encouraged by the Alabama congressional delegation, the U.S. Post Office issued a 19-cent stamp honoring Sequoyah as the premier stamp in its new Great American Series on December 27, 1980. Sequoyah Caverns, in Valley Head, DeKalb County, is named for Sequoyah.

Additional Resources

Foreman, Grant. Sequoyah. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1938.

Foster, George E. Se-Quo-Yah: The American Cadmus and Modern Moses. Philadelphia: Indian Rights Association, 1885.

Kilpatrick, Jack Frederick. Sequoyah of Earth and Intellect. Austin, Texas: Encino Press, 1965.