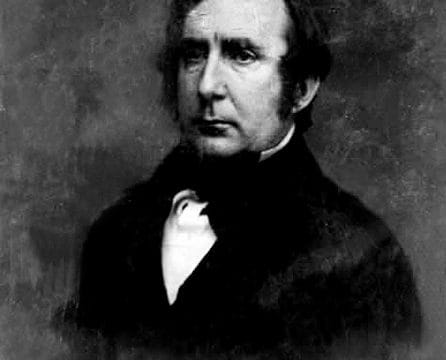

John McKinley

John McKinley (1780-1852) became the first Alabama resident to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court, from 1838 to 1852. Although he made little impact in American constitutional development, McKinley enjoyed a long and relatively successful political career, and he contributed much to Alabama’s early history and development in his role as a land speculator, legislator, and senator.

John McKinley

McKinley was born on May 1, 1780, in Culpepper County, Virginia, to Andrew McKinley and Mary (Logan) McKinley. His family soon thereafter moved to Frankfort, Kentucky, and by 1800 McKinley was practicing law. In 1818, he moved to Alabama with a small group of Kentuckians and established a residence and legal practice in Huntsville. McKinley also actively engaged in land speculation, and he and his fellow investors purchased large tracts of land for resale to incoming settlers. He and several other investors, including Gen. John Coffee and future president Andrew Jackson, organized the Cypress Land Company, which purchased thousands of acres in present-day Lauderdale County, and, as one of the principal founders of the city of Florence, he oversaw much of the town’s early development. McKinley also was one of the founding members of the Presbyterian Church in Florence, was instrumental in founding one of the first public schools in the region, and donated the land that eventually housed Athens State College. McKinley also served on the original board of trustees for the University of Alabama and helped plan the campus design and curriculum.

John McKinley

McKinley was born on May 1, 1780, in Culpepper County, Virginia, to Andrew McKinley and Mary (Logan) McKinley. His family soon thereafter moved to Frankfort, Kentucky, and by 1800 McKinley was practicing law. In 1818, he moved to Alabama with a small group of Kentuckians and established a residence and legal practice in Huntsville. McKinley also actively engaged in land speculation, and he and his fellow investors purchased large tracts of land for resale to incoming settlers. He and several other investors, including Gen. John Coffee and future president Andrew Jackson, organized the Cypress Land Company, which purchased thousands of acres in present-day Lauderdale County, and, as one of the principal founders of the city of Florence, he oversaw much of the town’s early development. McKinley also was one of the founding members of the Presbyterian Church in Florence, was instrumental in founding one of the first public schools in the region, and donated the land that eventually housed Athens State College. McKinley also served on the original board of trustees for the University of Alabama and helped plan the campus design and curriculum.

Soon after arriving in Alabama, McKinley ran for a circuit court judgeship. Although he allied himself early with Huntsville’s powerful Planter’s and Merchant’s Bank faction led by Gov. William Wyatt Bibb and notable political figures John Williams Walker and Clement Comer Clay, he still lost. In August 1820, McKinley was elected as a state representative from Madison County, then lost a bid for the U.S. Senate in 1822 when William Kelly, a candidate supported by Gov. Israel Pickens and Sen. William Rufus King, defeated McKinley by a one-vote margin.

During the next few years, McKinley slowly disassociated himself from the Huntsville faction, also known as the Broad River Group, and joined the rising political movement led by Andrew Jackson, hero of the Creek War of 1813-14. Though he was by temperament more in unison with conservative forces, McKinley grasped the power of Jacksonian Democracy, a political movement popular from around 1815 to around 1840 during which many voting restrictions were lifted and the electorate was greatly enlarged. McKinley astutely recognized its popularity among Alabamians. By 1826, when he again announced his candidacy to fill the Senate seat vacated by Israel Pickens, McKinley was within the Jackson camp. Clement Comer Clay, McKinley’s opponent, also claimed to be a Jacksonian but showed continued allegiance to Jackson’s rival John Quincy Adams. As a result, McKinley was viewed as the more ardent Jacksonian and won the seat by a vote of 41 to 38.

While in the Senate, McKinley focused on reforming federal land-grant laws to reduce the price of land. He also hoped to pass a measure granting Alabama 400,000 acres of land that the state could sell to fund a canal around Muscle Shoals, an area of the Tennessee River that was virtually impassable and thus impeded the transportation of cotton to market. The canal project, ultimately completed in 1836 with both state and federal funds, had long been desired by northwest Alabama residents, and McKinley, who had since relocated to Florence, understood the potential economic benefits it could bring to the area. Though he supported President Jackson on almost every issue, Sen. McKinley voted to override Jackson’s veto of the Maysville Road Bill, an internal improvement project of great importance to Kentucky and somewhat resembling the Muscle Shoals canal project that he so strongly advocated. McKinley’s anti-veto vote and support for internal improvement projects made his allegiance to Jackson questionable; his opponents also accused him of obstructing passage of the Indian Removal Act, which was strongly supported by the president and extremely popular among Alabamians. When McKinley sought reelection in 1830, Gov. Gabriel Moore openly opposed his candidacy, and McKinley lost.

McKinley returned to Florence and in 1831 was elected as a state representative from Lauderdale County. In 1832, he won election to the U.S. House of Representatives. McKinley continued to support reductions in federal land prices and more liberal credit for small farmers. After serving his two-year term, he decided not to seek reelection but remained politically active, serving as a Democratic elector for the 1836 presidential contest and staunchly supporting Martin Van Buren’s candidacy. He also returned to Florence and was elected again to the state legislature. McKinley’s desire to return to the state house seems to have been based on his desire to defeat Gabriel Moore’s bid for the U.S. Senate. In November 1836, largely as a result of Jackson’s repudiation of Moore for his earlier tacit support of nullification—a doctrine that espoused a belief that states had the authority to nullify federal laws—McKinley easily won the Senate seat against the former governor.

McKinley’s second term as a senator was brief. When Congress enacted legislation in 1837 that increased the number of U.S. Supreme Court justices from seven to nine, Pres. Van Buren offered one of the new posts to McKinley, who accepted and resigned from the Senate. McKinley then moved his family to Louisville, Kentucky, to be centrally located between his circuit—which initially included Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas—and Washington, D.C. Although he continued to spend much time in Mobile, the seat of the Fifth circuit, he never again resided in Alabama. McKinley took his seat on the Supreme Court in January 1838. One of the principal burdens of McKinley’s post was the immense size of his circuit, which required that he spend much time and effort traveling to his eight separate circuit courts.

McKinley wrote a scant 22 opinions during his 14 years on the bench, several of which were dissenting opinions in the interest of preserving states’ rights. One of the few cases for which McKinley is noted rose to the circuit level during his first year on the bench. Bank of Augusta v. Earle considered whether states could prohibit corporations in other states from doing business within their borders. McKinley ruled at the circuit level in 1838 that corporations could not operate within another state without the state’s permission. As the Bank of Augusta, Georgia, wanted to establish a branch in Alabama, McKinley’s ruling meant that Alabama had the right to determine whether that bank could function within the state. In the national economic scheme, McKinley’s ruling would severely limit corporation’s business activities, a development that would weaken the economy. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, where Daniel Webster represented the bank and argued no state had the right to exclude any corporation from engaging in interstate business. Because the issue fundamentally involved Congress’s constitutional authority to regulate interstate trade, it surprised few people when the Court reversed McKinley’s opinion by an 8-1 ruling, with McKinley issuing the lone dissent.

A second notable case centering on states’ rights in which McKinley played a fundamental role was Pollard v. Hagan, which involved congressional authority to regulate federal lands within territories. McKinley argued that the federal government could not regulate the land but only hold it in trust as the territory was a state-to-be and entitled to the same rights and privileges as the original states. Therefore, he argued, land grants made by Congress to various citizens of Mobile during Alabama’s territorial stage were nullified. A majority of the justices accepted McKinley’s argument, which supported proponents of states’ rights.

McKinley’s majority opinion in the Pollard case marked the high point of his years on the bench. By 1845, his health began to fail, and he spent less and less time either on circuit or in Washington. McKinley died at the age of 72 in Louisville, Kentucky, on July 19, 1852. His seat on the Supreme Court passed to another Alabamian, John Archibald Campbell.

Historians have offered various assessments of McKinley’s tenure on the Supreme Court that range from insignificant to average. Most describe his ability as moderate, his impact insignificant, and his contributions as minimal. A few point to the Pollard case as a significant reaffirmation of states’ rights, whereas others note that his ruling in the Bank of Augusta case enabled the Court to reaffirm a nationalistic definition of the commerce clause. Thus, McKinley’s circuit court decision indeed made an impact on constitutional history, albeit one that he did not prefer.

Additional Resources

Brown, Steven. John McKinley and the Antebellum Supreme Court: Circuit Riding in the Old Southwest. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012.

Gatell, Frank Otto. “John McKinley.” In The Justices of the United States Supreme Court, 1789-1969: Their Lives and Major Opinions. 4 volumes, edited by Leon Friedman and Fred Israel. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1969.

Hicks, Jimmie. “Associate Justice John McKinley: A Sketch.” Alabama Review 18 (July 1965): 227-33.

Martin, John M. “John McKinley: Jacksonian Phase.” Alabama Historical Quarterly 28 (Spring-Summer 1966): 7-31.

Thornton, J. Mills. “John McKinley.” In American National Biography, edited by John Garraty. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.