William "W. C." Handy

A native of Florence, Lauderdale County, W. C. Handy (1873-1958) was a songwriter, arranger, music publisher, and folklorist who became known as the “Father of the Blues” for his contributions to that musical genre. Among the most important American songwriters between the years 1910 and 1925, Handy introduced blues into the mainstream of popular culture by writing down and combining fragments of melodies and words, turning these into complete written compositions, and disseminating them via sheet music, performances, and recordings. His boyhood home in Florence now operates as a museum and library in his honor.

W. C. Handy, ca. 1940s

William Christopher Handy was born on November 16, 1873, to Charles Bernard Handy and Elizabeth Brewer. He was the son and grandson of ministers in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He had a brother and a half-sister from his father’s second marriage after the death of his mother. The family was relatively prosperous and owned land in Florence. They provided Handy with a thorough education in public schools, including basic musical skills such as ear training and note reading. Handy’s father discouraged secular music and urged his son to play the harmonium (reed organ) at his church, where the young Handy gained an understanding of hymns and spirituals. Handy was exposed to a variety of traditional secular music in his early years as well, despite his father’s wishes. He learned folk and popular tunes from an itinerant fiddler known as “Uncle Whit” Walker in addition to traditional African American rhythmic patterns.

W. C. Handy, ca. 1940s

William Christopher Handy was born on November 16, 1873, to Charles Bernard Handy and Elizabeth Brewer. He was the son and grandson of ministers in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He had a brother and a half-sister from his father’s second marriage after the death of his mother. The family was relatively prosperous and owned land in Florence. They provided Handy with a thorough education in public schools, including basic musical skills such as ear training and note reading. Handy’s father discouraged secular music and urged his son to play the harmonium (reed organ) at his church, where the young Handy gained an understanding of hymns and spirituals. Handy was exposed to a variety of traditional secular music in his early years as well, despite his father’s wishes. He learned folk and popular tunes from an itinerant fiddler known as “Uncle Whit” Walker in addition to traditional African American rhythmic patterns.

W. C. Handy Cabin

By the age of 16, Handy was creating four-part vocal arrangements of popular songs and singing them in “barbershop quartet” style harmonies with friends from school. He was also intrigued by the minstrel show musicians who came through Florence and played popular marches and cakewalks. Although he had earned a teacher’s certificate from Huntsville Teachers Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1892, he found better paying work at the Bessemer Iron Works outside Birmingham. Looking for adventure, Handy took to the road with a vocal quartet, which ran low on funds and became stranded in St. Louis in 1892. There, he first heard snatches of folk material that would later go into his most famous composition, “St. Louis Blues.”

W. C. Handy Cabin

By the age of 16, Handy was creating four-part vocal arrangements of popular songs and singing them in “barbershop quartet” style harmonies with friends from school. He was also intrigued by the minstrel show musicians who came through Florence and played popular marches and cakewalks. Although he had earned a teacher’s certificate from Huntsville Teachers Agricultural and Mechanical College in 1892, he found better paying work at the Bessemer Iron Works outside Birmingham. Looking for adventure, Handy took to the road with a vocal quartet, which ran low on funds and became stranded in St. Louis in 1892. There, he first heard snatches of folk material that would later go into his most famous composition, “St. Louis Blues.”

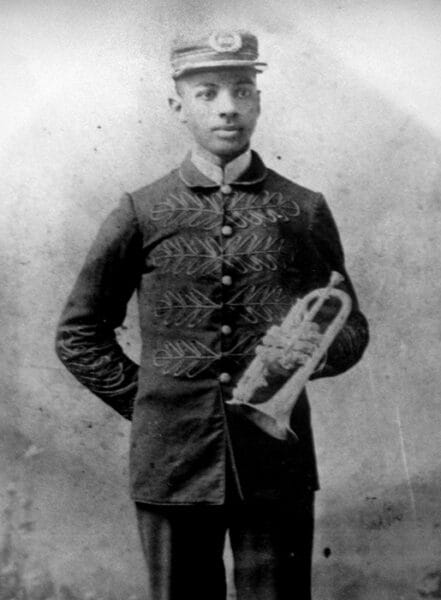

Handy spent most of 1893 through 1896 in Evansville, Indiana, and nearby Henderson, Kentucky, playing cornet in brass bands and developing his musical skills while working as a laborer. He was also earning local renown as a musician, and in August of that year he joined the famed Mahara’s Minstrels as cornetist with its marching band. During a four-year stint with the troupe, which toured as far as Canada and Cuba, Handy became a seasoned music arranger, director, and multi-instrumentalist, as well as the show’s cornet soloist. By 1898, he was being singled out for praise in the press. That same year, he married Elizabeth Price of Henderson, with whom he would have six children.

Handy, W. C.

In 1900, Handy became a music teacher at the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College in Normal (present-day Alabama A&M University). Tiring of the musical conservatism of the institution after two years, he returned to minstrelsy for a season. He received better job offers and in 1903 settled in Clarksdale, Mississippi, a regional market town in the Delta, to lead the town brass band. Over the next two years, he travelled widely in the region, where blues music was emerging, and he wrote down bits of melodies and lyrics that he heard sung by itinerant balladeers.

Handy, W. C.

In 1900, Handy became a music teacher at the Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical College in Normal (present-day Alabama A&M University). Tiring of the musical conservatism of the institution after two years, he returned to minstrelsy for a season. He received better job offers and in 1903 settled in Clarksdale, Mississippi, a regional market town in the Delta, to lead the town brass band. Over the next two years, he travelled widely in the region, where blues music was emerging, and he wrote down bits of melodies and lyrics that he heard sung by itinerant balladeers.

As Handy’s fame spread, he was drawn north to Memphis and was living there by the end of 1905. Just one of many aspiring musicians in a town with well-established bands, he sought help from the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal order that had sponsored his Clarksdale band. By 1909, Handy was a leading area bandleader, and in the mayoral election of that year he was hired to draw crowds for candidate Edward Crump. He won the election, and Handy’s catchy campaign song, “Mr. Crump,” swept town. Three years later, Handy combined the folk-based “Mr. Crump” with some original ragtime elements in a piano instrumental that he called “The Memphis Blues,” which he published himself in 1912. This clever composition caught the attention of publisher Theron Bennett, who convinced Handy to sell him the rights for $100. The following year, Bennett republished “The Memphis Blues” with lyrics, and the song was a hit. Handy was stung by the realization that he had signed away a considerable profit, but the lyrics praised Handy and his Memphis band and spread his renown.

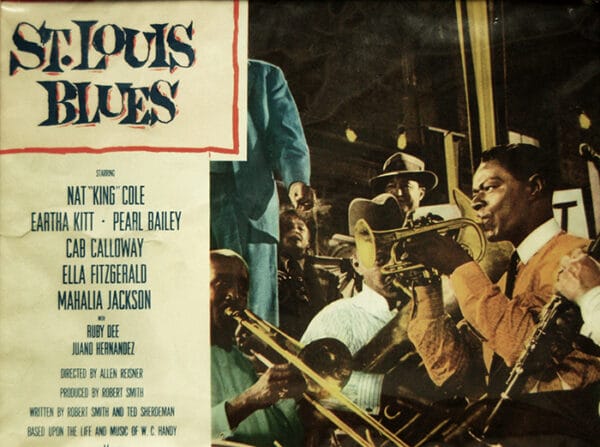

In 1907, Handy met Harry Pace, a brilliant young businessman from Covington, Georgia, and they teamed up in 1913 to found the Pace & Handy Music Company in Memphis. Their first publications, some with lyrics by Pace, were mediocre, but in 1914 Handy penned his masterpiece, “St. Louis Blues.” Unlike “The Memphis Blues,” “St. Louis Blues” was a genuine blues piece, and the first published blues to include a section in a minor key. The rhythm for this section is a habanera, or tango, with a sultry air. The song has three sections in all and allows for a variety of tempi, moods, and interpretations. Early recordings of “St. Louis Blues” tend to be brisk, in keeping with the mania for dancing during the World War I years, although it was only a minor hit during the first few years after its release. Beginning around 1921, it grew in popularity and became an immense hit that made it the second-most recorded piece in the history of jazz and much-performed in blues, folk, country, and pop settings. The 1925 version, featuring Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong, set the standard for slower, bluesier versions. Handy co-wrote the 1929 movie St. Louis Blues, which starred Smith.

St. Louis Blues

Handy produced a string of hits between 1914 and 1921, including “Yellow Dog Blues,” “Joe Turner Blues,” “Aunt Hagar’s Children Blues,” and “Beale Street Blues.” With sales from sheet music and royalties from recordings (including Handy’s own first records in 1917), Pace & Handy prospered. The pair took offices in New York City’s Times Square and moved into townhouses in Harlem. Early in 1921, Pace struck out on his own to found Black Swan Records, the first successful African American record company. Most of the best talent in the office, excited by the new opportunity, left with Pace. At the same time there was a downturn in business, and, in a cruel twist of fate, Handy suffered an infection that left him temporarily blind and with diminished sight after his recovery. His brother Charles and sister-in-law Ruth worked nights and weekends at the office shipping music and answering mail, and with the help of a few remaining staff members, Handy managed to hold on to his business, reincorporated as Handy Brothers Music Company. By the mid-1920s, his fortunes were improving. In 1925, he was interviewed by the lawyer and folk music scholar Abbe Niles, and together the pair created the remarkable Blues: An Anthology, combining enlightening commentary with numerous music examples. Handy was now becoming a household name in America; he crowned this success with a concert featuring his music at Carnegie Hall in 1928. With his hit-writing days waning, he turned to arranging spirituals and publishing music by other composers.

St. Louis Blues

Handy produced a string of hits between 1914 and 1921, including “Yellow Dog Blues,” “Joe Turner Blues,” “Aunt Hagar’s Children Blues,” and “Beale Street Blues.” With sales from sheet music and royalties from recordings (including Handy’s own first records in 1917), Pace & Handy prospered. The pair took offices in New York City’s Times Square and moved into townhouses in Harlem. Early in 1921, Pace struck out on his own to found Black Swan Records, the first successful African American record company. Most of the best talent in the office, excited by the new opportunity, left with Pace. At the same time there was a downturn in business, and, in a cruel twist of fate, Handy suffered an infection that left him temporarily blind and with diminished sight after his recovery. His brother Charles and sister-in-law Ruth worked nights and weekends at the office shipping music and answering mail, and with the help of a few remaining staff members, Handy managed to hold on to his business, reincorporated as Handy Brothers Music Company. By the mid-1920s, his fortunes were improving. In 1925, he was interviewed by the lawyer and folk music scholar Abbe Niles, and together the pair created the remarkable Blues: An Anthology, combining enlightening commentary with numerous music examples. Handy was now becoming a household name in America; he crowned this success with a concert featuring his music at Carnegie Hall in 1928. With his hit-writing days waning, he turned to arranging spirituals and publishing music by other composers.

The Great Depression cut into Handy’s business, but with the royalties from his early hits, the business survived, and by the end of the 1930s, a new wave of swing arrangements was making Handy money again. The late 1930s and early 1940s brought tumultuous developments in Handy’s life. His wife died, as did one of his three grown daughters. In 1940, he regained control of his first hit, “The Memphis Blues,” after the rights on the song had elapsed and from it earned additional income. In 1941, after almost a decade’s work, he published his autobiography, Father of the Blues, which immediately became a classic first-hand account of American music and history. In December 1943, while in the subway in Harlem, Handy lost his way, fell on to the train tracks, and was knocked unconscious. Only the quick thinking of two men on the platform saved him from a grisly death; however, thereafter he was permanently blind.

W. C. Handy Birthplace, Museum, and Library

Around this time Handy moved to Yonkers, just north of New York City, and continued to publish new compositions, mostly by others, into the early 1950s. He appeared repeatedly on television’s Ed Sullivan Show and fronted a band at Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s first inaugural ball. His sons W. C. Handy Jr. and Wyer Owens Handy and daughter Katherine eventually joined in running the business. At the age of 80, Handy married his longtime personal assistant Irma Louise Logan. After his death on March 28, 1958, Handy was mourned throughout the world; among the most famous of Americans, he was honored by an estimated 150,000 persons at his funeral in New York City. A film loosely based on his life and starring fellow Alabamian Nat “King” Cole, St. Louis Blues, came out just after Handy’s death.

W. C. Handy Birthplace, Museum, and Library

Around this time Handy moved to Yonkers, just north of New York City, and continued to publish new compositions, mostly by others, into the early 1950s. He appeared repeatedly on television’s Ed Sullivan Show and fronted a band at Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s first inaugural ball. His sons W. C. Handy Jr. and Wyer Owens Handy and daughter Katherine eventually joined in running the business. At the age of 80, Handy married his longtime personal assistant Irma Louise Logan. After his death on March 28, 1958, Handy was mourned throughout the world; among the most famous of Americans, he was honored by an estimated 150,000 persons at his funeral in New York City. A film loosely based on his life and starring fellow Alabamian Nat “King” Cole, St. Louis Blues, came out just after Handy’s death.

Handy was honored by the United States with a postage stamp in 1969; statues bearing his likeness stand in Florence and Memphis, and a block of 52nd Street in Manhattan was renamed in his honor. Many music awards and festivals bear his name; Florence hosts the annual weeklong W. C. Handy Music Festival, which features concerts, lectures, and other events to celebrate the city’s most famous native son. His compositions continue to be revived, particularly “St. Louis Blues,” one of the most frequently recorded compositions in history. Among New York’s oldest independent family owned African American businesses, Handy Brothers Music Company is still run by family members on Broadway. In 2018, the city of Florence signed documents transferring the Handy birthplace and museum back to the Handy family; it will be run by the nonprofit W.C. Handy Foundation.

Additional Resources

Handy, W. C. Blues, An Anthology. Introduction by Abbe Niles. New York: Boni & Boni, 1926.

———. Father of the Blues. New York: Macmillan and Co., 1941.

Hurwitt, Elliott S. “W. C. Handy” in International Dictionary of Black Composers. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn for the Center for Black Music Research, 1999.