Southern Baptists in Alabama

Montgomery First Baptist Church

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is the largest denomination in Alabama. In 2021, nearly 800,000 of Alabama‘s 4.9 million people belonged to churches affiliated with the SBC. In addition, nearly three-quarters of a million more Baptists belonged to churches affiliated with African American Baptist groups such as the National Baptist or Progressive Baptist conventions. Other blacks and whites belonged to traditional Baptist denominations such as Free Will or Primitive Baptist churches. According to a 2022 study by Pew Research, 31 percent of all state residents described themselves as Baptists of one kind or other. The denomination benefited from its loose organization, local church autonomy, democratic organization, emotional revivalism, appeal to ordinary people, lack of educational requirements for pastors, and bi-vocational ministers (men who worked secular jobs for their primary income while performing ministerial duties as their avocation in small churches unable to financially support a full-time pastor).

Montgomery First Baptist Church

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is the largest denomination in Alabama. In 2021, nearly 800,000 of Alabama‘s 4.9 million people belonged to churches affiliated with the SBC. In addition, nearly three-quarters of a million more Baptists belonged to churches affiliated with African American Baptist groups such as the National Baptist or Progressive Baptist conventions. Other blacks and whites belonged to traditional Baptist denominations such as Free Will or Primitive Baptist churches. According to a 2022 study by Pew Research, 31 percent of all state residents described themselves as Baptists of one kind or other. The denomination benefited from its loose organization, local church autonomy, democratic organization, emotional revivalism, appeal to ordinary people, lack of educational requirements for pastors, and bi-vocational ministers (men who worked secular jobs for their primary income while performing ministerial duties as their avocation in small churches unable to financially support a full-time pastor).

Baptist Doctrine and the Church’s Success

Many factors explain Baptist success. From the state’s beginning, people in Alabama distrusted authority and elites of all kinds. Few possessed wealth, and most were unsure about whether education was worth the expense and effort needed to obtain it. Politicians catered to the common man and were contemptuous of centers of wealth.

Baptist doctrine and church organization paralleled these democratic characteristics. Baptists extolled the priesthood of each believer (meaning that individuals could approach God directly without the intervention of a priest or pastor) and the absolute autonomy of each congregation. Responsible persons (generally defined as at least of teen age because Baptists do not baptize infants) could approach God directly, repent of their sins, accept unmerited grace (grace which they did nothing to earn by their behavior), make a profession of faith in Jesus Christ as personal savior, be baptized by total immersion in a creek, river, lake, or baptismal pool, and never fall from grace (that is, never lose the salvation gained). Baptist churches expected members to adhere to strong moral codes, condemning at various times dancing, attending plays or movies, listening to rock-and-roll music, drinking alcoholic beverages, smoking tobacco products, gambling, or working on Sunday.

The fact that the denomination had no educational requirements for ministers meant that any male (not a female) could experience a “call” from God to preach, announce that fact, and begin preaching in a church that invited him or on a street corner if he preferred. Members were generally poor, churches small and isolated in rural areas, and services infrequent. At first, quarter-time churches predominated, holding a long worship service once a month on Sunday, usually preceded on Saturday by a business meeting where some members disciplined other members who committed unethical and immoral acts that might embarrass the congregation. Once a year during, “lay-by time,” usually in August or early September when crop cultivation ended and farmers impatiently awaited the harvest, preachers and visiting evangelists conducted camp-meeting revivals. Families might travel many miles to camp for a week behind a church or next to a river or mountain to listen to four or five sermons a day, “get saved,” and not incidentally, socialize with friends and relatives, court potential mates, trade horses, conduct other business, or just rest from their arduous labors.

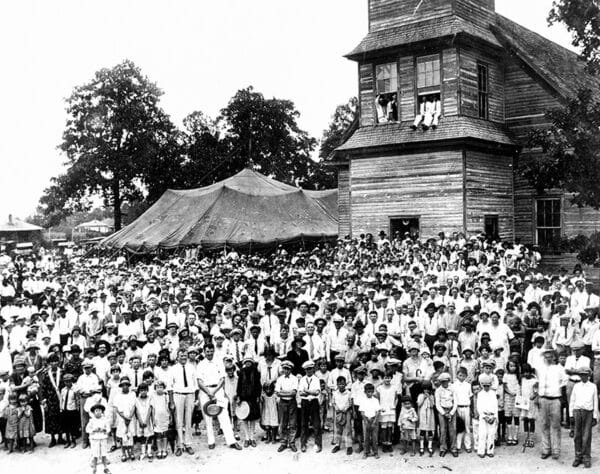

Revival at Fairmont Baptist Church

Baptist theology stems largely from Calvinism, the belief that an all-knowing and all-powerful God has determined people’s fate since creation. Some Baptists took Calvinism to such an extreme that they saw no need for colleges, missionaries, Sunday Schools, temperance societies, or any other denominational agencies; God had “predestined” them to salvation already, and no human effort would change the outcome. Missionary Baptists, who funded and sent out individuals to convert others to Christianity, rejected such hyper-Calvinism, convinced that human effort was part of God’s plan for salvation. Still other Baptists were nearly as theologically Arminian (an older theology that rejected predestination) as Methodists, believing that every person had free will and could accept or reject God’s entreaties. By the 1830s and 1840s, debates over Calvinism were splitting Baptists into competing branches, with the hyper-Calvinists increasingly called Primitive Baptists, and their competitors Missionary Baptists. Not surprisingly, those who aggressively tried to convert others came to outnumber those who did not.

Revival at Fairmont Baptist Church

Baptist theology stems largely from Calvinism, the belief that an all-knowing and all-powerful God has determined people’s fate since creation. Some Baptists took Calvinism to such an extreme that they saw no need for colleges, missionaries, Sunday Schools, temperance societies, or any other denominational agencies; God had “predestined” them to salvation already, and no human effort would change the outcome. Missionary Baptists, who funded and sent out individuals to convert others to Christianity, rejected such hyper-Calvinism, convinced that human effort was part of God’s plan for salvation. Still other Baptists were nearly as theologically Arminian (an older theology that rejected predestination) as Methodists, believing that every person had free will and could accept or reject God’s entreaties. By the 1830s and 1840s, debates over Calvinism were splitting Baptists into competing branches, with the hyper-Calvinists increasingly called Primitive Baptists, and their competitors Missionary Baptists. Not surprisingly, those who aggressively tried to convert others came to outnumber those who did not.

If churches chose to join an organization, it could exercise no substantial control over them, leaving individual congregations to decide issues for themselves by majority vote. Within a county or group of counties, churches might form loose associations that voluntarily cooperated on matters of common concern. In October 1823, churches statewide sent messengers or delegates to a meeting in Greensboro. Although these messengers represented only themselves in forming a state Baptist convention (an annual meeting that conducted business for the churches and later a bureaucracy created to conduct business in the interval between the annual meetings), their congregations generally endorsed their decisions. Subsequently, the state convention met annually in the fall to conduct business of common consent, such as establishing colleges or raising money for missionaries.

Antebellum Baptists

Alabama Baptist Building

Before the Civil War, Baptist churches reflected the gender, class, and racial divisions of southern society. For instance, many church buildings had separate doors and seating for men and women, with younger children sitting with the women. Church buildings were simple and unadorned, with rough-hewn pews. The congregations were concerned with liturgical aspects, such as common prayers, choirs, music books, stained glass windows, incense, and ministers wearing robes, and tended to have an altar in the center of the worship area, with the pulpit for preaching off to the side. The spatial arrangement emphasized adoration and worship rather than proclamation as the focus of devotion. But for Baptists, the Word, which was spoken from behind the pulpit or read from the Holy Bible, carried ultimate authority. Consequently, Baptists became famous for their charismatic, spellbinding preachers. Worship also featured music, often unaccompanied by instruments at first and “lined out” by a leader who first would read several lines of a hymn that the congregation would then sing because few churches contained hymn books and because many participants could not read.

Alabama Baptist Building

Before the Civil War, Baptist churches reflected the gender, class, and racial divisions of southern society. For instance, many church buildings had separate doors and seating for men and women, with younger children sitting with the women. Church buildings were simple and unadorned, with rough-hewn pews. The congregations were concerned with liturgical aspects, such as common prayers, choirs, music books, stained glass windows, incense, and ministers wearing robes, and tended to have an altar in the center of the worship area, with the pulpit for preaching off to the side. The spatial arrangement emphasized adoration and worship rather than proclamation as the focus of devotion. But for Baptists, the Word, which was spoken from behind the pulpit or read from the Holy Bible, carried ultimate authority. Consequently, Baptists became famous for their charismatic, spellbinding preachers. Worship also featured music, often unaccompanied by instruments at first and “lined out” by a leader who first would read several lines of a hymn that the congregation would then sing because few churches contained hymn books and because many participants could not read.

Judson College

Alabama Baptists maintained an uneasy fraternity because of socio-economic and class differences. Baptists in poorer areas of north Alabama, the hilly regions of east Alabama, and the southeastern Wiregrass were less enthusiastic advocates of an educated ministry and of establishing institutions sponsored by the denomination than were Baptists in the Black Belt. Wealthy planters, many from New England where their Baptist forebears had attended township schools, were among the most enthusiastic advocates of establishing Baptist-sponsored colleges and publicly supported schools. They also were more likely to prefer a pastor who had attended college and were more willing to pay him a salary that allowed him to perform his ministerial duties full-time. The town of Marion, seat of Perry County government in the rich, cotton-growing Black Belt, became the unofficial Baptist capital of Alabama. Local Baptists founded Judson College for women in 1838; Howard College (now Samford University) for men three years later; a statewide newspaper, the The Alabama Baptist, in 1843; and the Board of Domestic Missions (later called the Home Mission Board) in 1845.

Judson College

Alabama Baptists maintained an uneasy fraternity because of socio-economic and class differences. Baptists in poorer areas of north Alabama, the hilly regions of east Alabama, and the southeastern Wiregrass were less enthusiastic advocates of an educated ministry and of establishing institutions sponsored by the denomination than were Baptists in the Black Belt. Wealthy planters, many from New England where their Baptist forebears had attended township schools, were among the most enthusiastic advocates of establishing Baptist-sponsored colleges and publicly supported schools. They also were more likely to prefer a pastor who had attended college and were more willing to pay him a salary that allowed him to perform his ministerial duties full-time. The town of Marion, seat of Perry County government in the rich, cotton-growing Black Belt, became the unofficial Baptist capital of Alabama. Local Baptists founded Judson College for women in 1838; Howard College (now Samford University) for men three years later; a statewide newspaper, the The Alabama Baptist, in 1843; and the Board of Domestic Missions (later called the Home Mission Board) in 1845.

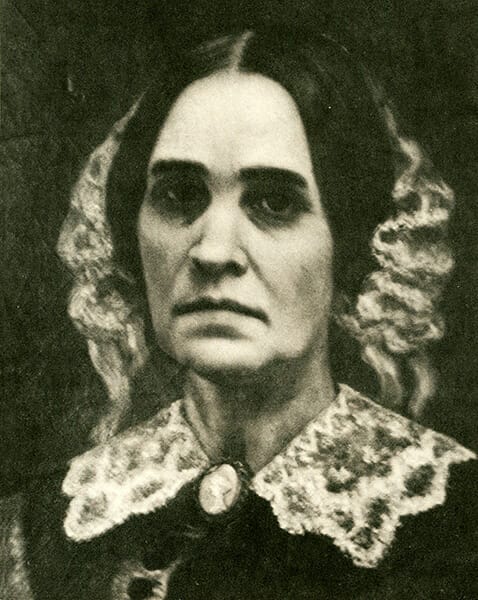

Julia Tarrant Barron

In the antebellum era, many distinguished state leaders were Baptists. Basil Manly Sr. was valedictorian of his class at the University of South Carolina, pastor of the South’s first Baptist church in Charleston, South Carolina, president of the University of Alabama, and first chaplain of the Confederate Congress in Montgomery. Hosea Holcombe was one of the state’s first historians. Julia Tarrant Barron, a prosperous Marion businesswoman and planter, co-founded both Judson and Howard colleges and was co-owner of the Alabama Baptist, the state’s denominational newspaper. Eliza Sexton Shuck and Martha Foster Crawford were both distinguished missionaries.

Julia Tarrant Barron

In the antebellum era, many distinguished state leaders were Baptists. Basil Manly Sr. was valedictorian of his class at the University of South Carolina, pastor of the South’s first Baptist church in Charleston, South Carolina, president of the University of Alabama, and first chaplain of the Confederate Congress in Montgomery. Hosea Holcombe was one of the state’s first historians. Julia Tarrant Barron, a prosperous Marion businesswoman and planter, co-founded both Judson and Howard colleges and was co-owner of the Alabama Baptist, the state’s denominational newspaper. Eliza Sexton Shuck and Martha Foster Crawford were both distinguished missionaries.

Race Relations

Early Baptist churches were almost always biracial in membership if not in function. By 1847, the state’s most influential association, the Alabama Association centered in Montgomery, had 3,573 members, 1,790 of them black. The state’s most influential church, Montgomery First Baptist, had 411 members, only 96 of them being white. Yet no African Americans served as pastor of such a church, although they were usually allowed to preach to black members and occasionally became so renowned that whites listened attentively as well. African Americans did not usually serve as deacons, elders, Sunday School teachers, or in any other official church capacity. Church rolls listed the full names of white (and also usually free black members) but typically only the first names of enslaved members together with the names of their owners.

Stone Street Baptist Church

Race later divided Baptists as deeply as class. Few all-black Baptist churches existed in Alabama before the Civil War. The Stone Street Baptist Church in Mobile, an African American congregation, claims to date from 1806, but there is no documentation to support the claim. The first recorded congregation (biracial in nature) is believed to be Flint River Baptist Church, organized in October 1808. That congregation, however, soon withdrew from fellowship with Missionary Baptists and joined the Primitive Baptist denomination. The first church (also biracial) affiliated continuously with the Missionary State Baptist Convention was Enon Baptist (present-day Huntsville First Baptist), organized on June 3, 1809.

Stone Street Baptist Church

Race later divided Baptists as deeply as class. Few all-black Baptist churches existed in Alabama before the Civil War. The Stone Street Baptist Church in Mobile, an African American congregation, claims to date from 1806, but there is no documentation to support the claim. The first recorded congregation (biracial in nature) is believed to be Flint River Baptist Church, organized in October 1808. That congregation, however, soon withdrew from fellowship with Missionary Baptists and joined the Primitive Baptist denomination. The first church (also biracial) affiliated continuously with the Missionary State Baptist Convention was Enon Baptist (present-day Huntsville First Baptist), organized on June 3, 1809.

The early churches blurred distinctions between piety and politics. Most endorsed slavery and opposed consumption of alcohol. In 1844, the state convention passed the Alabama Resolutions, which denounced the national Baptist Home Mission Society for refusing to appoint a Georgia man as a missionary because he owned slaves. Arguing that only local congregations could determine eligibility for such service, the state convention vowed to withhold the money it had raised for missions from the national organization and urged other slave-owning states to do likewise. This action resulted in an 1845 meeting of southern Baptists in Savannah, Georgia, at which the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) was formed, dividing the American Baptist family permanently.

White Alabama Baptists subsequently became ardent secessionists and preached the inevitable victory of the Confederacy and God’s plan to redeem America through a restoration of old-time Baptist piety and autonomy. Wrong on both scores, they watched their men die in war, Union victory, and the withdrawal of virtually all African American members from their churches into black Baptist churches.

Post-War Developments

Woman’s Missionary Union

Women emerged in new roles after the Civil War. In 1879, they organized a women’s central mission’s committee, the beginning of the Women’s Missionary Union (WMU). A fully autonomous Baptist women’s auxiliary of the SBC, the Alabama WMU officially dates from 1888. In 1913, more than five years before women could vote in American elections, the state Baptist convention allowed women messengers to attend and vote. Selma‘s Kathleen Mallory was selected as national WMU director and moved the organization’s headquarters from Baltimore to Birmingham. Although the WMU represented overwhelmingly conservative evangelical women, many of their number also became active in the woman suffrage movement and in other early twentieth-century reforms, including opposition to the sale of alcoholic beverages, child labor, legalized prostitution, and the convict-lease system, and in support of prison, health, and educational reforms. Because of congregational autonomy, individual Baptist churches could and did occasionally ordain women to preach and serve as deacons.

Woman’s Missionary Union

Women emerged in new roles after the Civil War. In 1879, they organized a women’s central mission’s committee, the beginning of the Women’s Missionary Union (WMU). A fully autonomous Baptist women’s auxiliary of the SBC, the Alabama WMU officially dates from 1888. In 1913, more than five years before women could vote in American elections, the state Baptist convention allowed women messengers to attend and vote. Selma‘s Kathleen Mallory was selected as national WMU director and moved the organization’s headquarters from Baltimore to Birmingham. Although the WMU represented overwhelmingly conservative evangelical women, many of their number also became active in the woman suffrage movement and in other early twentieth-century reforms, including opposition to the sale of alcoholic beverages, child labor, legalized prostitution, and the convict-lease system, and in support of prison, health, and educational reforms. Because of congregational autonomy, individual Baptist churches could and did occasionally ordain women to preach and serve as deacons.

First Baptist Church of Selma

In fact, the years between 1900 and 1940 featured a robust debate among white Alabama Baptists regarding the role of Christ and culture. Many of their leaders—Frank Willis Barnett, A. J. Dickinson, Leslie L. Gwaltney—propounded socialistic business and labor reforms such as abolition of child labor or espoused modernist theology such as belief in biological evolution. Membership exploded between 1900 and 1930 but slowed during the subsequent Great Depression. Buoyed by evangelist Billy Graham’s national revivals and returning optimism after the World War II, growth renewed in the 1940s. In 1940, one in seven Alabamians was a Baptist. A decade later, the ratio was one in six, and by 1970, one in four.

First Baptist Church of Selma

In fact, the years between 1900 and 1940 featured a robust debate among white Alabama Baptists regarding the role of Christ and culture. Many of their leaders—Frank Willis Barnett, A. J. Dickinson, Leslie L. Gwaltney—propounded socialistic business and labor reforms such as abolition of child labor or espoused modernist theology such as belief in biological evolution. Membership exploded between 1900 and 1930 but slowed during the subsequent Great Depression. Buoyed by evangelist Billy Graham’s national revivals and returning optimism after the World War II, growth renewed in the 1940s. In 1940, one in seven Alabamians was a Baptist. A decade later, the ratio was one in six, and by 1970, one in four.

A split occurred within the SBC in 1979 between conservatives and moderates over the denomination’s direction. It resulted in fundamentalists taking control and spilled over into Alabama. Some large congregations affiliated themselves with the new more liberal Alliance for Baptists or the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. Growth stalled both within the state and the SBC, with actual membership declines in some years. Although Alabama’s overwhelmingly conservative state convention and Baptist colleges avoided the worst of the controversy, state convention resolutions on hot-button culture-war issues, such as legalized gambling, abortion, and homosexuality, replaced traditional attacks on alcohol consumption, dancing, and Sunday activities. Fundamentalists denounced Samford University for hiring allegedly modernistic professors and even threatened to defund the school. Both black and white Baptists also lost members to Pentecostal and independent mega-churches.

By 1995, 52 percent of SBC churches in Alabama had “plateaued” (an SBC designation for churches whose resident membership had increased by less than 10 percent during the previous five years or was actually declining). Some 70 percent of Baptist Sunday schools were in a similar predicament. Baptisms peaked in the SBC in 1980 at 430,000 (the year so-called conservatives won control of the national convention) before falling steadily to less than 300,000 in 2015. The conservative victory over convention “moderates” did nothing to correct membership decline, however. Baptisms in Alabama SBC churches followed the national trend: from 35,000 in 1972-73 to below 25,000 by end of century, to 16,000 in 2015. In 2015, the state’s 3,242 SBC churches represented a decline of seven churches from a decade earlier, and church membership had dropped from 1,132,400 in 2005 to 946,714 in 2016. Gifts from Alabama SBC churches to the denomination’s Cooperative Program (CP) for missions declined from a peak of $45 million in 2008 for eight of the following nine years, the longest downward cycle since the CP began in 1925. Despite such declines, the SBC still ranked far ahead of any other denomination. The closest competitor to Baptist affiliation in Alabama (37 percent of the state’s church members) was Roman Catholicism, with only 13 percent. Nationally, the dominant pattern saw the decline of all mainline religious denominations, including the SBC, in favor of non-denominational mega-churches, pentecostalism, and “nones” (respondents who increasingly selected “none” when asked their religious affiliation and represent the fastest growing sector of Americans).

Additional Resources

Fallin, Wilson, Jr. Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Flynt, Wayne. Alabama Baptists: Southern Baptists in the Heart of Dixie. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

Holcombe, Hosea. History of the Rise and Progress of the Baptists of Alabama. Philadelphia: King and Baird Printers, 1840.

Reid, A. Hamilton. Baptists in Alabama: Their Organization and Witness. Montgomery: Paragon Press, 1967.

Riley, B. F. A Memorial History of the Baptists of Alabama. Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1923.