Organized Labor in Alabama

Unionized Iron Workers, ca. 1910

The history of labor relations in Alabama is both similar to and different from that of other southern states. Alabama shares their legacy of racial strife and a largely rural populace, but the rise of the Birmingham steel industry, beginning in the 1870s, and the textile industry in the northern part of the state, created a distinct situation in which African American and white laborers sometimes found common ground in their protests against often harsh working conditions. Despite their common interests, workers were often pitted against one another by owners, who used underlying racial tensions to thwart the efforts of union organizers. Labor unions began to finally enjoy some local bargaining power after World War II, and from the mid-1960s onward, African Americans began to score some important gains over segregation and advance into high-skilled, higher-paying industrial positions long forbidden to them. But during the past 25 years, many of those jobs and the industries that provided them have disappeared in the wave of globalization. As Alabama enters a new era of industrialization, the fate of organized labor remains to be seen.

Unionized Iron Workers, ca. 1910

The history of labor relations in Alabama is both similar to and different from that of other southern states. Alabama shares their legacy of racial strife and a largely rural populace, but the rise of the Birmingham steel industry, beginning in the 1870s, and the textile industry in the northern part of the state, created a distinct situation in which African American and white laborers sometimes found common ground in their protests against often harsh working conditions. Despite their common interests, workers were often pitted against one another by owners, who used underlying racial tensions to thwart the efforts of union organizers. Labor unions began to finally enjoy some local bargaining power after World War II, and from the mid-1960s onward, African Americans began to score some important gains over segregation and advance into high-skilled, higher-paying industrial positions long forbidden to them. But during the past 25 years, many of those jobs and the industries that provided them have disappeared in the wave of globalization. As Alabama enters a new era of industrialization, the fate of organized labor remains to be seen.

Slavery and its legacy cast a long shadow over the early industrial history of Alabama. Before the war, enslaved blacks performed virtually all of the field labor on the cotton plantations in the Black Belt, whereas the majority of nonslaveholding whites were concentrated in north Alabama, the growing capital city at Montgomery, and the port of Mobile. By the late antebellum period, enslaved workers who had developed skills as carpenters, blacksmiths, and other trades were increasingly hired out by their owners, who controlled their wages. This practice increased tensions between slaves and white “mechanics” (skilled workers), who charged that their employers resorted to slave labor mainly because it was cheaper. In addition, legislative restrictions on black mobility just before the war made it essentially impossible for black freedmen to get work.

While slavery lasted, the antagonisms between black slave laborers and white laborers persisted. Emancipation and the highly polarized political situation during Reconstruction brought no immediate solution. Many of Alabama’s former slaveowners hoped to retain the essence, if not the full legal standing, of slavery, whereas freed men and women were determined to make a complete break with their former status. A wave of violence carried out against former slaves prompted the migration of freedpeople into urban areas. Among those left on the plantations, a movement known as the Union Leagues developed under the direction of the Republican Party. These leagues in rural Alabama and Mississippi often resembled trade unions, organizing work stoppages to demand higher wages and to protest continued mistreatment.

In 1867, one of the first instances of an organized work stoppage in Alabama occurred. Mobile authorities reported an attempt at a general strike by workers in the city that was supported most strongly by black laborers on the levee, in the saw-mills, and among those employed at odd jobs, although it was apparently instigated by sympathetic whites. This early incident in a growing movement showed that despite deep racial divisions, whites and blacks occasionally could work together toward common interests. By the late 1870s, these tenuous attempts at cooperation were reflected in the collaboration between white laboring men and Mobile’s black voters in independent political campaigns led by Workingmen’s parties and, later, the Greenbacks and Populists.

Tenant Farming in Eutaw

When Reconstruction ended in Alabama in 1874, heightened racial divisions and considerable violence severely curtailed the early efforts of former slaves to organize. The vast majority of the state’s male laboring population, both white and black, continued to eke out a living as sharecroppers, agricultural laborers, or independent farmers on small plots that they owned themselves. Women, however, had few employment choices beyond the home or farm: substantial numbers of black women worked as domestics, or maids, in white homes, and by the end of the century white women were moving increasingly into the textile mills, but most women worked in the home. In short, conditions outside of a few population centers were unfavorable for labor organizing.

Tenant Farming in Eutaw

When Reconstruction ended in Alabama in 1874, heightened racial divisions and considerable violence severely curtailed the early efforts of former slaves to organize. The vast majority of the state’s male laboring population, both white and black, continued to eke out a living as sharecroppers, agricultural laborers, or independent farmers on small plots that they owned themselves. Women, however, had few employment choices beyond the home or farm: substantial numbers of black women worked as domestics, or maids, in white homes, and by the end of the century white women were moving increasingly into the textile mills, but most women worked in the home. In short, conditions outside of a few population centers were unfavorable for labor organizing.

Industrialization

In the late nineteenth century, industrial centers emerged in the state, concentrated in the north. Textile mills drew on female and child labor in Decatur, Huntsville, Fort Payne, and Florence, and iron and steel production sprang up in Gadsden and in the planned industrial town of Anniston. The most important break with the state’s agrarian legacy was the growing iron and steel industry taking shape in and around Birmingham in the late 1870s. Eventually, industrialization began to shift economic power away from Black Belt planters and toward those who dominated the new industries.

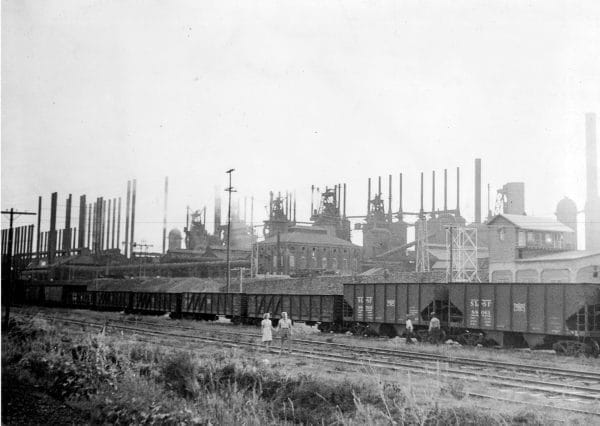

TCI’s Steelworks in Ensley

The rise of the steel industry, and the mining of the coal and iron ore on which it depended, brought waves of black and white migrants to the Magic City in search of better wages and relief from rural poverty. Early on, a mixed workforce began to emerge in the Birmingham district. Employers in the iron foundries and steel mills maintained a labor hierarchy with a small number of relatively well-paid white craftsmen at its top and a much larger, mostly black workforce performing the menial and more dangerous work for lower wages. This stratification helped to reinforce existing racial divisions. A small number of immigrants came into the area, attracted by the mills and mines, but the bulk of the workforce was drawn from Alabama and surrounding states.

TCI’s Steelworks in Ensley

The rise of the steel industry, and the mining of the coal and iron ore on which it depended, brought waves of black and white migrants to the Magic City in search of better wages and relief from rural poverty. Early on, a mixed workforce began to emerge in the Birmingham district. Employers in the iron foundries and steel mills maintained a labor hierarchy with a small number of relatively well-paid white craftsmen at its top and a much larger, mostly black workforce performing the menial and more dangerous work for lower wages. This stratification helped to reinforce existing racial divisions. A small number of immigrants came into the area, attracted by the mills and mines, but the bulk of the workforce was drawn from Alabama and surrounding states.

In the coal and iron ore mines, blacks and whites demonstrated a greater willingness to work together. Interracial cooperation was encouraged by the rise of southern populism, a political movement emphasizing the rights of the common people that drew both black and white miners into the Greenback Labor party. The Populist movement also drew strength from the presence of a national workers’ organization, the Knights of Labor, which established local assemblies throughout the coalfields and in Birmingham itself. Both of these organizations were compelled to organize across the color line, an exceptional and often dangerous move as formal segregation became established in the aftermath of Reconstruction.

Erskine Ramsay Guards, 1894

Miners worked long hours in dangerous conditions for employers who maintained their competitive advantage over northern rivals by paying the lowest wages possible. In addition, their jobs often were threatened by the practice of hiring convict laborers, who were leased to industry by state and county prisons. Tensions resulted in a series of bitter strikes between 1888 and the close of the nineteenth century. After briefly attempting to assert their grievances through a statewide union, Alabama’s miners affiliated with the newly formed United Mineworkers of America in April 1890, becoming known as UMW District 20. By the end of the century, the UMW had managed to organize the Birmingham district, and an uneasy truce between the leading employers and their interracial workforce descended on the coalfields.

Erskine Ramsay Guards, 1894

Miners worked long hours in dangerous conditions for employers who maintained their competitive advantage over northern rivals by paying the lowest wages possible. In addition, their jobs often were threatened by the practice of hiring convict laborers, who were leased to industry by state and county prisons. Tensions resulted in a series of bitter strikes between 1888 and the close of the nineteenth century. After briefly attempting to assert their grievances through a statewide union, Alabama’s miners affiliated with the newly formed United Mineworkers of America in April 1890, becoming known as UMW District 20. By the end of the century, the UMW had managed to organize the Birmingham district, and an uneasy truce between the leading employers and their interracial workforce descended on the coalfields.

In Mobile, Montgomery, and Birmingham, skilled craftsmen organized into affiliate chapters of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and in Birmingham the local trades’ council launched a newspaper aimed at union members, the Labor Advocate. Composed almost exclusively of skilled white men in the building trades, these craft unions, along with the older railroad organizations, typically excluded African Americans from membership. The result was that by the end of the nineteenth century the small pool of skilled black workers that had emerged out of slavery had largely disappeared because all that was open to African Americans was unskilled work at lower rates of pay.

The Early Twentieth Century

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, two major confrontations erupted in the coalfields, and more followed during the upheavals that accompanied the entry of the United States into World War I. In 1903, the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company—the largest coal employer in the state—announced it would no longer bargain with the UMW. A bitter strike over recognition erupted in 1908, involving upwards of 20,000 black and white miners. Marked by frequent armed clashes and provocative attempts by some prominent mine operators to inflame racial tensions, the strike was broken in August. Many of the most experienced miners left the state, seeking better wages and conditions in West Virginia and elsewhere.

World War I complicated the situation for both employers and workers. Increased industrial demand caused by the war opened up opportunities in northern industry for both blacks and whites and helped spark an African American exodus from the South that became known as the Great Migration. Employers in Alabama had to raise wages and improve conditions to retain a labor force. In addition, during this period many rural workers moved to the city, eager to escape a hard and unpredictable farm life. Also, to prevent disruption of industrial production during wartime, the federal government intervened and guaranteed higher wages while discouraging strikes and ordering workers to “work or fight.”

Renewed Labor Unrest and Mixed Success

As they did throughout the United States, workers in Alabama welcomed the end of the war as an opportunity to secure the higher wages and benefits that they could not get during the war. Military spending had brought some prosperity to parts of the state by expanding shipbuilding in Mobile, munitions plants in the Tennessee Valley, and the strategically vital steel production in Birmingham. But many workers felt that the profits made during the war had been spread unevenly. Trade unionists launched a major drive to organize the steel industry workforce in 1918, making their first genuine effort to appeal to both blacks and whites. However, their attempt met strong resistance from major steel employers, and their efforts failed in the face of employer-sponsored vigilante violence and lack of federal support. The 1918 steel strike was a prelude to a longer and more bitter coal strike in the Birmingham district in 1920 and 1921, ending with the miners’ failure to win recognition as bargaining agents for the miners.

Failed strikes ushered in a period of slow progress for state labor organizations. As in the rest of the nation, renewed labor activity in Alabama did not occur until the Great Depression, when sheer desperation forced groups of workers to unite and take a stand. Spurred on by left-wing activists associated with the Communist Party, the overwhelmingly black Alabama Sharecroppers’ Union organized in 1931 but suffered heavy repression, including a fatal shootout with police during a meeting at a church at Camp Hill in Tallapoosa County, with one killed and five wounded. In 1935, longshoremen in Mobile—almost all of them African Americans—engaged in a difficult strike for union recognition that saw some of them beaten and jailed.

Gadsden Textile Strike

The previous year, more than 23,000 of Alabama’s mostly female textile workers had launched a series of strikes in defiance of their employers and the United Textile Worker’s Union (UTW) to protest violations of New Deal legislation. Across much of the South, workers charged employers with ignoring the National Recovery Act’s prohibitions against child labor and its new rules on wages and hours. Their actions eventually forced a general strike, encompassing textile workers throughout the United States, that is still considered the largest industry-wide conflict in the nation’s history. Despite a brave effort by textile unionists, once again workers failed to secure their goals, and many of the them found themselves “blacklisted”—barred from future employment in the industry. Defeat in the strike brought an end to the UTW’s influence in the mills.

Gadsden Textile Strike

The previous year, more than 23,000 of Alabama’s mostly female textile workers had launched a series of strikes in defiance of their employers and the United Textile Worker’s Union (UTW) to protest violations of New Deal legislation. Across much of the South, workers charged employers with ignoring the National Recovery Act’s prohibitions against child labor and its new rules on wages and hours. Their actions eventually forced a general strike, encompassing textile workers throughout the United States, that is still considered the largest industry-wide conflict in the nation’s history. Despite a brave effort by textile unionists, once again workers failed to secure their goals, and many of the them found themselves “blacklisted”—barred from future employment in the industry. Defeat in the strike brought an end to the UTW’s influence in the mills.

The textile workers’ militancy reflected a dramatic shift in the national mood, which resulted in the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) after the mid-1930s. The CIO had been founded by AFL dissidents who were disenchanted with that organization’s conservative leadership, particularly their unwillingness to organize the millions of unskilled workers concentrated in industry. In Alabama as elsewhere, the miners’ union provided much of the muscle and resources employed to organize the unskilled. These industrial unionists brought to the difficulties they faced in Alabama the mixed legacy of interracial unionism that the UMW had embodied in the state from the late nineteenth century.

Striking Mine Workers

The results of CIO organizing were uneven: Birmingham miners joined a national coal strike in 1933 and 1934, and after fierce confrontations that saw employer-paid security use machine guns at some mines and compelled then-Gov. Bibb Graves to deploy the National Guard, the miners secured union recognition—but little else. CIO officials hoped to work from this foundation to spread the union message across the district, and especially in the strategically important steel industry. But already entrenched racial divisions that were encouraged by employers hoping to prevent African Americans and whites from working together made organizing the steel industry difficult. In some towns, ordinances were passed prohibiting mixed-race union meetings. In the iron-ore mines, the CIO’s Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’ Union, with help from left-wing activists, organized effectively among the mostly black workforce, but in the steel mills organizing was more difficult. A failed strike at Republic Steel in 1936 weakened the movement, but CIO efforts compelled U.S. Steel to recognize the union in 1937. A long series of struggles during the next five years eventually brought all the major steel employers to recognize the union.

Striking Mine Workers

The results of CIO organizing were uneven: Birmingham miners joined a national coal strike in 1933 and 1934, and after fierce confrontations that saw employer-paid security use machine guns at some mines and compelled then-Gov. Bibb Graves to deploy the National Guard, the miners secured union recognition—but little else. CIO officials hoped to work from this foundation to spread the union message across the district, and especially in the strategically important steel industry. But already entrenched racial divisions that were encouraged by employers hoping to prevent African Americans and whites from working together made organizing the steel industry difficult. In some towns, ordinances were passed prohibiting mixed-race union meetings. In the iron-ore mines, the CIO’s Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’ Union, with help from left-wing activists, organized effectively among the mostly black workforce, but in the steel mills organizing was more difficult. A failed strike at Republic Steel in 1936 weakened the movement, but CIO efforts compelled U.S. Steel to recognize the union in 1937. A long series of struggles during the next five years eventually brought all the major steel employers to recognize the union.

World War II and the Late Twentieth Century

World War II brought changes similar to those that occurred during World War I, but in some ways they were even more profound. Because a large percentage of working-age males joined the military, labor was in severely short supply. Under this pressure, some of the barriers to skilled industrial employment were eliminated—temporarily, at least—for women and African Americans, who had been previously barred from well-paid work. As it had during World War I, the wartime labor shortage increased workers’ bargaining power and created a context in which unions were able to establish themselves on more stable foundations. The early postwar period would see a substantial increase in unionization in Alabama and indeed throughout the United States. New opportunities also aggravated historic tensions, however. In the Mobile shipyards, which employed more than 40,000 workers at the height of war production, white workers staged a bloody race riot in May 1943 after their employer agreed to comply with federal regulations and promote 12 black workers into skilled positions.

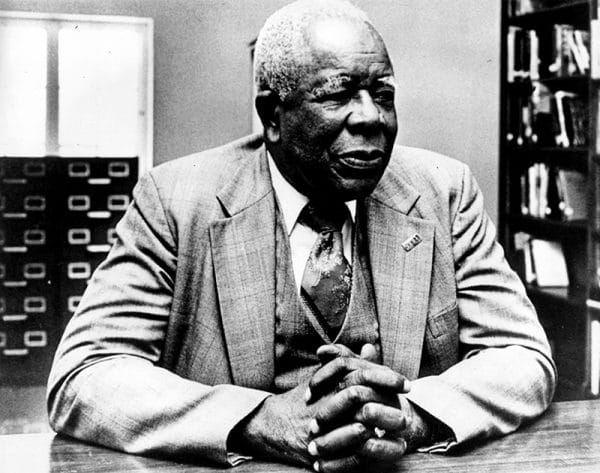

E. D. Nixon, 1984

Partly because of the confidence that they had gained during wartime in the military and in positions formerly closed to them, black southerners began to challenge racial segregation after the war as never before; unsurprisingly, the organized labor movement emerged from this important chapter with a mixed record. Important figures in the Montgomery bus boycott were experienced and committed trade unionists; local NAACP president E. D. Nixon was a longtime member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, for example, and Rosa Parks‘s husband Raymond had been active in left-wing labor circles since the 1930s. National labor unions such as the Packinghouse Workers and the United Autoworkers were outspoken in their support for the civil rights movement. In Birmingham, black union members from the steel plants and pipe shops served as bodyguards for civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth when he faced death threats because of his activism.

E. D. Nixon, 1984

Partly because of the confidence that they had gained during wartime in the military and in positions formerly closed to them, black southerners began to challenge racial segregation after the war as never before; unsurprisingly, the organized labor movement emerged from this important chapter with a mixed record. Important figures in the Montgomery bus boycott were experienced and committed trade unionists; local NAACP president E. D. Nixon was a longtime member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, for example, and Rosa Parks‘s husband Raymond had been active in left-wing labor circles since the 1930s. National labor unions such as the Packinghouse Workers and the United Autoworkers were outspoken in their support for the civil rights movement. In Birmingham, black union members from the steel plants and pipe shops served as bodyguards for civil rights leader Fred Shuttlesworth when he faced death threats because of his activism.

In contrast, large numbers of white workers, including trade unionists, increasingly opposed the civil rights movement. The cooperation between African American and white workers in the labor movement that had been present from the late nineteenth century virtually disappeared in the face of this increased racial tension. Many whites joined the rabidly pro-segregation White Citizen’s Councils and, in some places, the Ku Klux Klan. Klan Imperial Wizard Robert Shelton, for example, led a breakaway from the United Rubber Workers to protest the AFL-CIO’s support for civil rights. Whereas most of Alabama’s labor leaders supported demands for civil rights in hopes that restoring voting rights for black workers would help to break the influence that anti-union employers exerted in the state legislature, they faced a difficult task in trying to sell this idea to white rank-and-file workers.

Ironically, white workers opposed to black civil rights were defending privileges they were about to lose to much larger forces. Industrial employers across the United States reassessed their business strategies, which resulted in millions of industrial jobs being exported out of the United States in the last quarter of the twentieth century. Alabama was hit particularly hard by this aspect of globalization. The massive steel industry that had been built up for more than a century in northern Alabama was reduced to a shell of its former self, and textile production followed a similar path. Manufacturing in Birmingham accounted for nearly 30 percent of all jobs in 1960; by the first decade of the new century the figure was somewhere around 6 percent; coal and iron ore mining, which once employed up to 40,000 men, is now virtually nonexistent. Black workers, who had for so long been barred from many of the best-paying jobs in these industries, had finally begun to gain a foothold just as these industries began to collapse.

By the twenty-first century, levels of unionization in once heavily unionized Alabama had dropped from more than 30 percent after World War II to below 9 percent. The weakness of organized labor in recent years and the accompanying decline in wages has made the state attractive to automakers and other major employers seeking a base in the business-friendly South, but overall Alabama has still seen a steep decline in industrial employment from its historical high. That decline coincides with a rise in lower-paid service-sector jobs. Added to the complications rooted in historic race divisions, the state in recent years has seen a dramatic rise in immigration, particularly from Mexico and Central America, which has brought new racial tensions. In all of these new challenges and opportunities arising out of its relationship to a market-driven world economy, Alabama’s experience mirrors that of communities across the United States and beyond.

Further Reading

- Brown, Edwin L., and Colin J. Davis. It Is Union and Liberty: Alabama Coal Miners and the UMW. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Draper, Alan. Conflict of Interests: Organized Labor and the Civil Rights Movement in the South, 1954-1968. Ithaca: ILR Press, 1994.

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Urban Emancipation: Popular Politics in Reconstruction Mobile, 1860-1890. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002.

- Huntley, Horace and David Montgomery. Black Workers’ Struggle for Equality in Birmingham. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

- Kelly, Brian. Race, Class and Power in the Alabama Coalfields, 1908-1921. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

- McKiven, Henry M. Iron and Steel: Class, Race and Community in Birmingham, Alabama, 1875-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Nelson, Bruce. “Organized Labor and the Struggle for Black Equality in Mobile during World War II.” Journal of American History 80 (December 1993): 952-88.

- Salmond, John A. Southern Struggles: The Southern Labor Movement and the Civil Rights Struggle. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

- Woodrum, Robert H. “Everybody Was Black Down There”: Race and Industrial Change in the Alabama Coalfields. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.