Reconstruction in Alabama

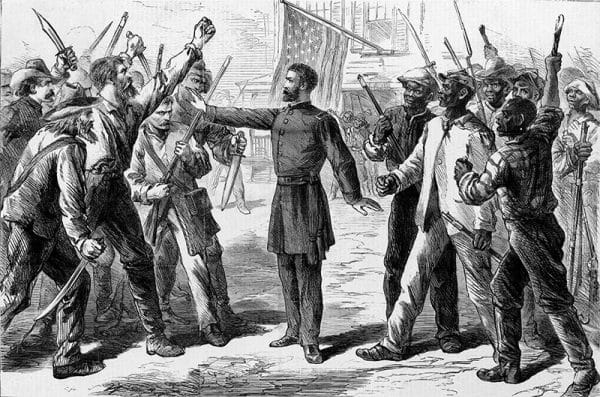

Freedmen’s Bureau Engraving

Reconstruction is the general term for the process of political and social realignments and readjustments in the South after the Civil War and Emancipation, often described as lasting from 1865 to 1877, although in Alabama it ended earlier, in 1874. Historians generally divide the period into two phases: Presidential Reconstruction and Congressional Reconstruction. Presidential Reconstruction began in 1865, when federal troops in Alabama began overseeing Emancipation, under the auspices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) and its head, Gen. Wager T. Swayne.

Freedmen’s Bureau Engraving

Reconstruction is the general term for the process of political and social realignments and readjustments in the South after the Civil War and Emancipation, often described as lasting from 1865 to 1877, although in Alabama it ended earlier, in 1874. Historians generally divide the period into two phases: Presidential Reconstruction and Congressional Reconstruction. Presidential Reconstruction began in 1865, when federal troops in Alabama began overseeing Emancipation, under the auspices of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) and its head, Gen. Wager T. Swayne.

Pres. Andrew Johnson set the initial policy, however, and he gave ex-Confederates latitude to reestablish race relations on the terms they supported. Despite the wishes of the Republican majority for protection of the civil rights for freedpeople and for barring the former elite from power, Johnson’s policies mostly prevailed for nearly the first two years after the war. President Johnson opposed federally guaranteed civil rights protection or extending voting rights to freedmen. He also favored rapid pardons for ex-Confederate leaders and quick reintegration into the Union for the 11 states formerly in rebellion.

In 1867, the Republican-dominated Congress took control of the Reconstruction process and attempted to expand and protect the civil rights of the formerly enslaved. This phase has alternately been called Radical Reconstruction, Military Reconstruction, and its most all-encompassing name, Congressional Reconstruction. During the next eight years, Unionists, federal officials, former Confederates, and freedpeople struggled to define Alabama’s political and social landscape. The federal government worked to rewrite Alabama’s constitution, freedmen founded political and workers’ rights organizations such as the Union League, and Democrats who favored states’ rights and white supremacy responded with legal action and, sometimes, terrorism in the form of intimidation, violence, and murder by the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups.

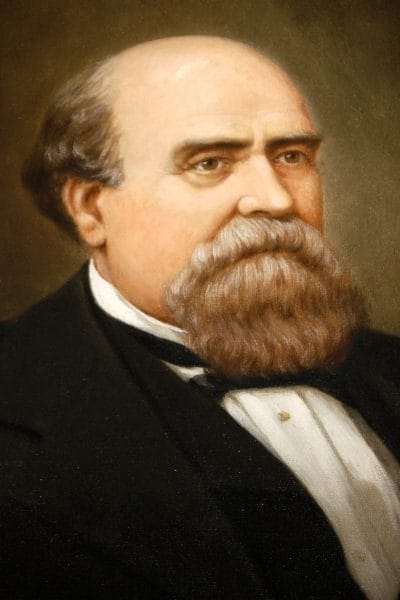

George S. Houston

In 1874, after several years of financial hardship, political intrigue, and continued maneuvering by Democrats, the ex-Confederate faction of Alabama regained the governor‘s office, with the election of George S. Houston. In the decades that followed, leading up to the 1901 Constitution, Alabama Democrats successfully overturned any expansion of voting rights for freedpeople and returned the state to the planters’ preferred focus on low taxes and minimal government regulation. This period is known as “Redemption,” so called because the white-supremacist Democrats who regained political power believed that the South had been “crucified” by federal tyranny and black rule and would now rise again to its former glory. The issues of black equality and suffrage that had been stirred in the Reconstruction Era simmered for decades in Alabama and elsewhere in the South until they boiled over in the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Alabama’s experience with Reconstruction was broadly representative of the other southern states, and the outcome was equally dire for the civil rights of the freedpeople and their supporters.

George S. Houston

In 1874, after several years of financial hardship, political intrigue, and continued maneuvering by Democrats, the ex-Confederate faction of Alabama regained the governor‘s office, with the election of George S. Houston. In the decades that followed, leading up to the 1901 Constitution, Alabama Democrats successfully overturned any expansion of voting rights for freedpeople and returned the state to the planters’ preferred focus on low taxes and minimal government regulation. This period is known as “Redemption,” so called because the white-supremacist Democrats who regained political power believed that the South had been “crucified” by federal tyranny and black rule and would now rise again to its former glory. The issues of black equality and suffrage that had been stirred in the Reconstruction Era simmered for decades in Alabama and elsewhere in the South until they boiled over in the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. Alabama’s experience with Reconstruction was broadly representative of the other southern states, and the outcome was equally dire for the civil rights of the freedpeople and their supporters.

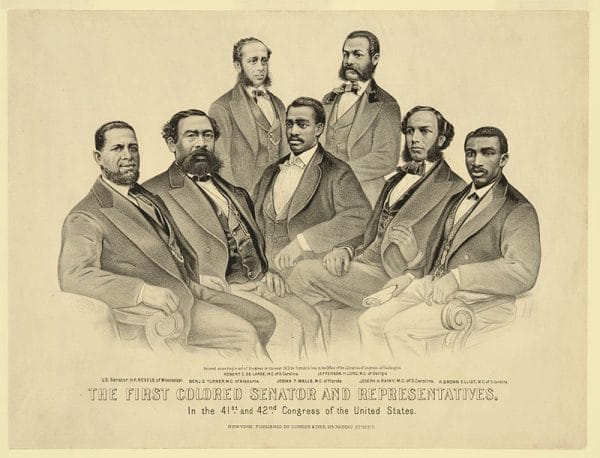

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

Overall, Reconstruction in Alabama is a mixed legacy. Freedpeople took advantage of the post-Civil War era to secure access to the public school system and basic equality before the law. Although less assertive in civil rights demands than in other states, the freedpeople in Alabama challenged the racial hierarchy effectively, which explains the depth and persistence of violent opposition by ex-Confederates, white supremacists, and the Ku Klux Klan. The long-term result of Reconstruction was to strengthen the most reactionary aspects of southern society—vigilantism, states’ rights militancy, and Democratic one-party rule—which became embodied in Jim Crow laws that pushed blacks out of Alabama and the South during the Great Migration. These factors set the stage for another confrontation with federal authority over civil rights nearly a century later.

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

Overall, Reconstruction in Alabama is a mixed legacy. Freedpeople took advantage of the post-Civil War era to secure access to the public school system and basic equality before the law. Although less assertive in civil rights demands than in other states, the freedpeople in Alabama challenged the racial hierarchy effectively, which explains the depth and persistence of violent opposition by ex-Confederates, white supremacists, and the Ku Klux Klan. The long-term result of Reconstruction was to strengthen the most reactionary aspects of southern society—vigilantism, states’ rights militancy, and Democratic one-party rule—which became embodied in Jim Crow laws that pushed blacks out of Alabama and the South during the Great Migration. These factors set the stage for another confrontation with federal authority over civil rights nearly a century later.

Additional Resources

Fitzgerald, Michael W. Splendid Failure: Postwar Reconstruction in the American South. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2007.

———. Reconstruction in Alabama: From Civil War to Redemption in the Cotton South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2017.

Fleming, Walter L. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. New York: Columbia University Press, 1905.

McMillan, Malcolm Cook. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1791-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. Spartanburg: The Reprint Company, 1978.