Republican Party in Alabama

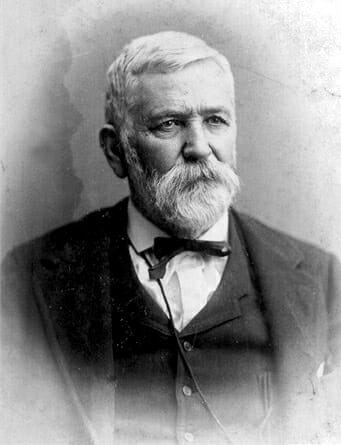

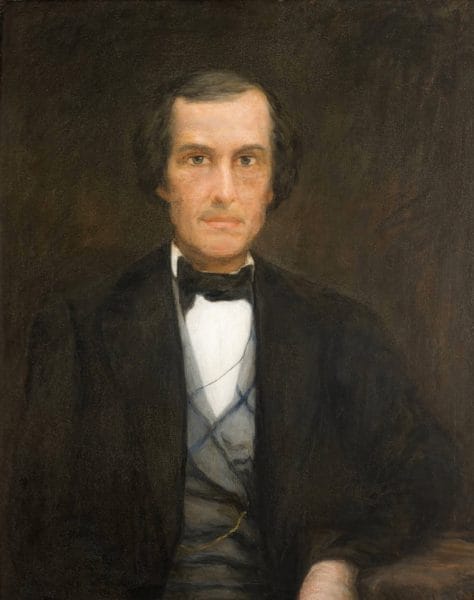

William Hugh Smith

Born out of the contentious sectional issues that led to the Civil War, the national Republican Party first appeared in Alabama during Reconstruction. During this period, Alabama Republicans included large number of blacks, especially newly freed slaves, as well as a mix of white Unionists, scalawags (white southerners who joined the Republican Party), and carpetbaggers (northern Republicans who migrated to the South) who collectively sought the presence of the federal government to reshape the economic, social, and political landscape of the state. The party struggled to survive in most of the state during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the Solid Democratic South held sway. It finally but slowly emerged as a viable second party after World War II and realigned itself over time. By the twenty-first century, most Republicans in Alabama were white, favored fiscal and social conservatism, and preferred that the federal government stay out of most state business.

William Hugh Smith

Born out of the contentious sectional issues that led to the Civil War, the national Republican Party first appeared in Alabama during Reconstruction. During this period, Alabama Republicans included large number of blacks, especially newly freed slaves, as well as a mix of white Unionists, scalawags (white southerners who joined the Republican Party), and carpetbaggers (northern Republicans who migrated to the South) who collectively sought the presence of the federal government to reshape the economic, social, and political landscape of the state. The party struggled to survive in most of the state during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the Solid Democratic South held sway. It finally but slowly emerged as a viable second party after World War II and realigned itself over time. By the twenty-first century, most Republicans in Alabama were white, favored fiscal and social conservatism, and preferred that the federal government stay out of most state business.

For most of its history in Alabama, the Republican Party was in the minority, lagging behind the Democrats in power, influence, and number of elected officials. William Hugh Smith was the first Republican governor in state history, but he served only briefly, from 1868 until 1870, as did the second, David P. Lewis (1872-1874). Guy Hunt, the third Republican elected governor in Alabama, assumed office more than a century later in 1987. Ironically, both Smith and Hunt faced ethics trouble; Smith’s financial decisions were discredited after he left office, and Hunt was removed from office in 1993 for financial misconduct. Hunt was later pardoned, somewhat controversially, but the furor over both governors indicates an important theme: when two-party politics have been present in Alabama, the landscape is rough-and-tumble. New controversies arose in the early twenty-first century when Democratic governor Don Siegelman was convicted of ethics violations amid charges of behind-the-scenes efforts to discredit him by the national and local Republican parties.

The Republican Party Emerges

The national Republican Party that formed in 1854 was comprised of abolitionists who wanted slavery ended immediately and antislavery members who opposed extending slavery into new federal territories and states. Because the overwhelming majority of Alabama politicians were directly or tangentially aligned with the interests of slavery, most Alabamians viewed the new party as a scourge. Although the 1854 elections made the Republicans a plurality in Congress, no Republican was on the ballot in Alabama that year. Even in the 1860 presidential election, Abraham Lincoln garnered no votes from the state, as most Alabama counties sided with Democratic vice president John C. Breckinridge, a Kentuckian who championed slavery and defended secession as constitutionally permissible. More than a few Alabama newspaper editors and political officials castigated the new political party as “Black Republicanism.”

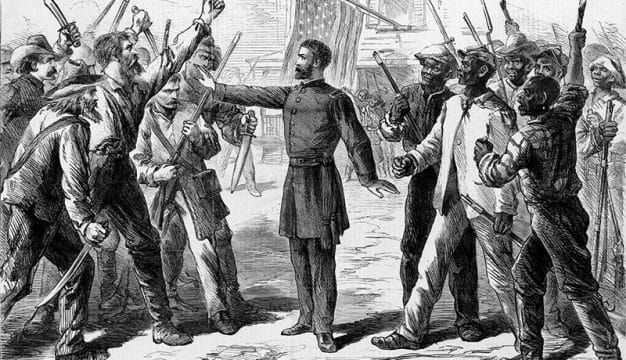

The election of delegates to the state secession convention indicated that Alabama did not universally support such a proposition. Rather, 54 percent of the elected delegates favored immediate secession, with some convinced that war was not inevitable. The rest of the delegates were cooperationists, who believed that remaining in the Union was the only option for preserving slavery. Throughout the war, dissent and party desertion grew in Alabama, although the Republican Party did not. Only after the Confederate government surrendered did the possibility of Republican rule emerge. During Reconstruction, as freed slaves and other blacks entered the political process as voters and candidates, a viable Republican Party grew closer to reality in Alabama. Although an August 1865 Constitutional Convention in Alabama tabled a resolution that might have granted black males the right to vote, the military presence in the state and a Congress dominated by Republicans, some of whom were truly radical, gave hope to some Unionists who began to identify with the Republican party.

Alexander H. Curtis

In June 1867 Alabama Republicans assembled in Montgomery for a convention that revealed numerous differences among the freedmen, white Unionists, scalawags, and carpetbaggers. Some favored black suffrage, whereas others were more reluctant. Most favored congressional Reconstruction and others found the sweeping platform of the Radical Republicans in Congress to be too much, too soon. By 1867, more blacks were registered to vote in Alabama than whites, and joining the party of Abraham Lincoln—the Great Emancipator—was an easy choice for blacks, who regarded the Democratic Party as the political arm of southern slavery. In October 1867, the state elected 100 delegates to yet another constitutional convention, of which 96 were Republicans that included 18 blacks. A new day had dawned in Alabama, with Republicans in control of the political process.

Alexander H. Curtis

In June 1867 Alabama Republicans assembled in Montgomery for a convention that revealed numerous differences among the freedmen, white Unionists, scalawags, and carpetbaggers. Some favored black suffrage, whereas others were more reluctant. Most favored congressional Reconstruction and others found the sweeping platform of the Radical Republicans in Congress to be too much, too soon. By 1867, more blacks were registered to vote in Alabama than whites, and joining the party of Abraham Lincoln—the Great Emancipator—was an easy choice for blacks, who regarded the Democratic Party as the political arm of southern slavery. In October 1867, the state elected 100 delegates to yet another constitutional convention, of which 96 were Republicans that included 18 blacks. A new day had dawned in Alabama, with Republicans in control of the political process.

Despite their ascendancy, Republicans in Alabama were more divided than united. North Alabamians viewed their political and economic priorities differently than some of their south Alabama neighbors and were generally less engaged in slavery and more likely to be subsistence farmers. In addition, many whites were suspicious of a society where blacks might be considered equals. Although the power of carpetbaggers has been overstated by some historians, native-born Alabamians were sometimes suspicious of outsiders even if they were in the same political party. In addition, blacks resented the fact that the first slate of Republican officials were all white, and the conflict was significant enough to lead to a decline in Republican voter registration in the last months of 1867 and the first months of 1868.

Election rules led to a curious result when the Republican’s new constitution was placed on the ballot for a state vote. A total of 50 percent of registered voters was required to vote in order to make the result binding. Hoping to derail the effort, Democrats instructed their members to register, thereby increasing the total number of legal voters, but then to refrain from voting on the constitution to avoid the 50 percent threshold. The strategy worked, albeit briefly. Because the total number of votes cast was less than 50 percent, the constitution was not adopted even though those who did vote enthusiastically supported the document by a large margin. Radical Republicans in Congress moved to readmit Alabama to the Union based on the new constitution, despite the state’s voter turnout, and overrode a veto by Pres. Andrew Johnson, who cited the 50-percent rule in his dissent.

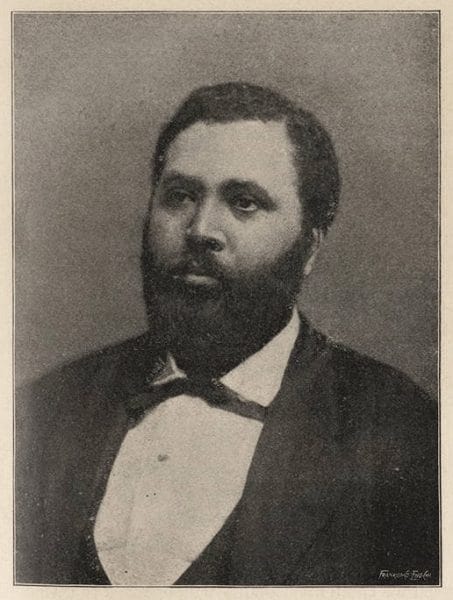

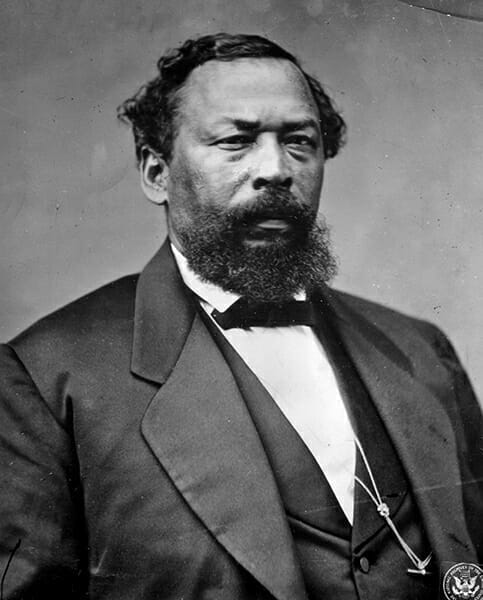

Benjamin S. Turner

Legally or not, Alabama was back in the Union and the Republicans were prepared to represent the state in the federal government. Republicans dominated the state’s congressional delegation for the next three elections, and three blacks— Benjamin Turner of Selma in the Forty-Second Congress, James T. Rapier of Montgomery in the Forty-Third Congress, and Jeremiah Haralson of Dallas County in the Forty-Fourth Congress—were among those the state sent to Washington. Within the state, the Republicans dominated the legislature, electing a combined total of 27 blacks to the House and Senate, and placing Smith, chair of the June 1867 Republican convention, in the governor’s office. Republicans supported internal improvements, such as railroad construction and waterway management, but many of their actions, particularly in support of railroad expansion, were plagued by charges of corruption. A combination of fraud and poor business practices doomed many of the railroad projects, making state bonds a bad investment and ruining the state’s credit rating. A new school system for blacks was undermined by white opposition and little funding. Indeed, revenues were inadequate to operate the existing school system, let alone one for whites and another for blacks. Whereas the Republicans proved able enough to write a new constitution and take control of government, governing was an entirely different manner, and the Republican’s racial, geographic, and political differences greatly hampered their efforts.

Benjamin S. Turner

Legally or not, Alabama was back in the Union and the Republicans were prepared to represent the state in the federal government. Republicans dominated the state’s congressional delegation for the next three elections, and three blacks— Benjamin Turner of Selma in the Forty-Second Congress, James T. Rapier of Montgomery in the Forty-Third Congress, and Jeremiah Haralson of Dallas County in the Forty-Fourth Congress—were among those the state sent to Washington. Within the state, the Republicans dominated the legislature, electing a combined total of 27 blacks to the House and Senate, and placing Smith, chair of the June 1867 Republican convention, in the governor’s office. Republicans supported internal improvements, such as railroad construction and waterway management, but many of their actions, particularly in support of railroad expansion, were plagued by charges of corruption. A combination of fraud and poor business practices doomed many of the railroad projects, making state bonds a bad investment and ruining the state’s credit rating. A new school system for blacks was undermined by white opposition and little funding. Indeed, revenues were inadequate to operate the existing school system, let alone one for whites and another for blacks. Whereas the Republicans proved able enough to write a new constitution and take control of government, governing was an entirely different manner, and the Republican’s racial, geographic, and political differences greatly hampered their efforts.

Decline of the Republican Party

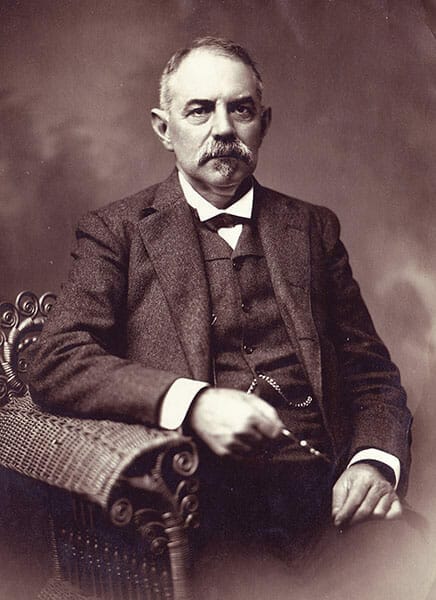

David P. Lewis, 1872

Gubernatorial and legislative corruption—nothing new in Alabama history—damaged the Republican Party’s political reputation among white voters. By 1870, the Ku Klux Klan was active in the state, targeting blacks, Republicans, and other undesirables. Whippings increased and a handful of murders and widespread threats reduced Republican voter turnout in 1870. Democrat Robert Lindsay narrowly defeated Smith, and although the Republicans recaptured the office in 1872 with David P. Lewis, their momentum was lost. Democrats suggested further Republican rule could result in sexual integration of the races and the eventual extinction of the white race. By 1874, the Democrats were simply more united than the Republicans on the issue of race and in their opposition to continued federal Reconstruction. Supported by Klan violence and the perception that Republicans had been corrupt, Democrats retook control in Alabama. Evidence exists that the Democrats prevented black Republicans from voting through violence and intimidation, destroyed marked ballots, and invited residents of Georgia to cross the border and vote for Democratic candidates. Although the Democrats clearly used racist appeals to attract voters in 1874, the larger issue remains that the Republicans themselves were divided on race: unable to win office without a racial coalition and unable to overlook racial differences while in power.

David P. Lewis, 1872

Gubernatorial and legislative corruption—nothing new in Alabama history—damaged the Republican Party’s political reputation among white voters. By 1870, the Ku Klux Klan was active in the state, targeting blacks, Republicans, and other undesirables. Whippings increased and a handful of murders and widespread threats reduced Republican voter turnout in 1870. Democrat Robert Lindsay narrowly defeated Smith, and although the Republicans recaptured the office in 1872 with David P. Lewis, their momentum was lost. Democrats suggested further Republican rule could result in sexual integration of the races and the eventual extinction of the white race. By 1874, the Democrats were simply more united than the Republicans on the issue of race and in their opposition to continued federal Reconstruction. Supported by Klan violence and the perception that Republicans had been corrupt, Democrats retook control in Alabama. Evidence exists that the Democrats prevented black Republicans from voting through violence and intimidation, destroyed marked ballots, and invited residents of Georgia to cross the border and vote for Democratic candidates. Although the Democrats clearly used racist appeals to attract voters in 1874, the larger issue remains that the Republicans themselves were divided on race: unable to win office without a racial coalition and unable to overlook racial differences while in power.

Democrats quickly moved to write yet another constitution, the fourth in only 15 years, and dominated the election of delegates. The 12 Republican delegates—including four blacks—were outnumbered by 80 Democrats and seven independents and were powerless to stop the drafting and ratification of the new document in 1875. In the governor’s office and in the legislature, Democrats, often called Bourbons or Redeemers, distanced themselves from internal improvements, a Republican imperative, and passed crop lien laws and other legislation that crippled both black and white sharecroppers, Democrat and Republican. In addition, Democrats began the long process of casting Reconstruction, through both academic history and public memory, as a period of horror for whites. The Republican Party survived but was rarely successful and only influential in portions of north Alabama.

Post-Reconstruction Republican Party

With little power base left, Republicans sought political partners from other opponents of the Democrats in order to create coalitions. Displaced sharecroppers and tenants, Greenbackers, Populists, the Agricultural Wheel, the Farmer’s Alliance, the National Grange of the Patrons of Husbandry, independents, industrial workers, blacks, and the remaining Republican remnant offered the possibility of many voters, but true fusion of all these disparate groups was difficult, especially given Democratic insistence that voters consider race first and class interests second. These various groups may have agreed on the broadest contours of economic and political reform but found little common ground on specific issues or solutions to problems.

Thomas Goode Jones

As farm protests and strikes among coal miners intensified, many working-class Alabamians came to believe that Black Belt planters and Birmingham industrial tycoons would never represent the interests of the working classes. In 1892, former Democratic agriculture commissioner Reuben Kolb challenged incumbent Democratic governor Thomas Goode Jones. Calling himself a “Jeffersonian Democrat,” Kolb garnered the support of farmers, blacks, Populists, and Republicans. The official election results indicated a victory for Jones, but Kolb and many other observers, including some Democrats, understood that the Democrats had earned their victory through chicanery. If voting records are to be believed, black Republicans in Black Belt counties enthusiastically supported Jones, something that defied logic. Democrats had supported lynching and reduced funding for black schools and pushed the state to legalize elements of segregation that were largely practiced already. Kolb ran unsuccessfully again in 1894—another controversial election replete with corruption and fraud—and Democrats secured their continued domination via the 1901 state constitution. Arcane rules, including the white primary and various disfranchisement schemes, provided the Democrats with clear campaign advantages. Although the Republicans continued to offer a limited slate of candidates in local and state elections, the Democratic Party, dedicated to white supremacy, was virtually unbeatable for decades.

Thomas Goode Jones

As farm protests and strikes among coal miners intensified, many working-class Alabamians came to believe that Black Belt planters and Birmingham industrial tycoons would never represent the interests of the working classes. In 1892, former Democratic agriculture commissioner Reuben Kolb challenged incumbent Democratic governor Thomas Goode Jones. Calling himself a “Jeffersonian Democrat,” Kolb garnered the support of farmers, blacks, Populists, and Republicans. The official election results indicated a victory for Jones, but Kolb and many other observers, including some Democrats, understood that the Democrats had earned their victory through chicanery. If voting records are to be believed, black Republicans in Black Belt counties enthusiastically supported Jones, something that defied logic. Democrats had supported lynching and reduced funding for black schools and pushed the state to legalize elements of segregation that were largely practiced already. Kolb ran unsuccessfully again in 1894—another controversial election replete with corruption and fraud—and Democrats secured their continued domination via the 1901 state constitution. Arcane rules, including the white primary and various disfranchisement schemes, provided the Democrats with clear campaign advantages. Although the Republicans continued to offer a limited slate of candidates in local and state elections, the Democratic Party, dedicated to white supremacy, was virtually unbeatable for decades.

Alabama Republicans and Presidential Politics

Alabama opposed Republican presidential candidates and the party in local, county, and state offices. After casting its electoral ballots for Republican Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and 1872, Alabama voted Democratic in every presidential election from 1876 until 1948. Whereas many Alabama Democrats favored the economic programs of the New Deal, including rural electrification, they opposed social programs that might threaten segregation. By 1948, Democratic president Harry S. Truman’s support for an integrated military and other civil rights legislation drew the ire of Alabama Democrats. In that first post-World War II election, Alabama strongly supported Dixiecrat J. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, an omen that the national Democratic Party was losing its grip on the state. Alabamians moved toward Republican presidential candidates and socially conservative candidates over the remainder of the twentieth century. The state supported conservative Democrat Harry Byrd of Virginia in 1960, favorite son George Wallace of the American Independent party in 1968, and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter in 1976, the one notable exception.

Party Realignment and Republican Ascendancy

Within the state, Republicans took advantage of the social liberalism of the Democratic Party and made inroads at the local, county, and state levels. Republican James D. Martin‘s narrow loss to incumbent Democratic senator Lister Hill in 1962 was a further portent of change. White Alabamians began voting for Republican candidates with increasing frequency and slowly changed their official party registration to Republican. Several factors account for these changes: support for integration and civil rights programs by national Democrats like John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson; realignment of the Democratic Party to include strong influence from blacks, social liberals, and union members; Gov. George Wallace’s constant bashing of both national Democrats and the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the growing conservatism of the national Republican Party; and economic changes that made Alabama more urban, less dependent on traditional agricultural products like cotton, and more dependent on technology.

Martin and state Republican Party chair John Grenier worked feverishly during the 1962 campaign against Hill and continued to organize and attract support through 1964. That year, five Republicans won congressional seats and nearly 100 Republicans won local campaigns. Part of Grenier’s success in awakening the slumbering state Republican Party can be traced to his strategy of courting young voters. Although a range of political ideas was apparent among state Republicans, they generally favored lower taxes, stridently opposed forced busing to achieve racial integration in public schools, and supported mandatory sentences for criminals.

Guy Hunt

State Republicans began to attract the attention of the national party as well. Montgomery businessman Winton Blount became president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and then was tapped by Pres. Richard Nixon as postmaster general, the first Alabamian named to a cabinet post in the twentieth century. Blount was unsuccessful in winning statewide office, but he used his influence and money to continue the rebuilding process begun by Martin and Grenier. Retired admiral Jeremiah Denton won a U.S. Senate seat in 1980. Prominent state Democrats, including Fob James, Charles Graddick, and Richard Shelby, switched parties. By the last two decades of the twentieth century, party realignment had led to legitimate two-party competition in the legislature, in local and county offices in various areas of the state, and in national politics.

Guy Hunt

State Republicans began to attract the attention of the national party as well. Montgomery businessman Winton Blount became president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and then was tapped by Pres. Richard Nixon as postmaster general, the first Alabamian named to a cabinet post in the twentieth century. Blount was unsuccessful in winning statewide office, but he used his influence and money to continue the rebuilding process begun by Martin and Grenier. Retired admiral Jeremiah Denton won a U.S. Senate seat in 1980. Prominent state Democrats, including Fob James, Charles Graddick, and Richard Shelby, switched parties. By the last two decades of the twentieth century, party realignment had led to legitimate two-party competition in the legislature, in local and county offices in various areas of the state, and in national politics.

Throughout the twentieth century, however, Republicans failed to control either the state legislature or the governor’s office. Martin had challenged Lurleen Wallace in 1966 but was turned back decisively. Montgomery mayor Emory Folmar threatened George Wallace in 1982 but was defeated as well. Republican Guy Hunt’s 1986 victory was as much the product of Democratic in-fighting as it was a statement that the Republican Party had fully arrived. Even Fob James’s 1994 narrow victory as a Republican might be attributed to national gains by the Republican Party that gave them control of Congress for the first time in four decades. But no such explanations exist for Republican Bob Riley’s gubernatorial victories in 2002 and 2006. The Republican party had proven itself to be capable of winning elections at every level of state government.

Kay Ivey

Even as the Republican Party has dominated local and statewide voting—98 of 140 total legislative seats were in GOP hands in 2017—governance has not proven to be smooth or effective. While various polls indicate Alabama is the most or one of the most politically conservative states in the country, other metrics indicate not much has changed with Republican ascendancy in terms of the state’s place in national rankings of education, public health, or state income. Ethical and personal scandals drove Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard, and Gov. Robert Bentley from office all within the course of a calendar year. One result was the state’s first Republican female governor, Kay Ivey. Other results, including party realignment or electoral gains by the Democratic Party, seem possible, but unlikely. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, the Republican Party was typically supported by white males, economic elites, evangelicals, and individuals who identify themselves as socially and fiscally conservative. A notable exception occurred in 2021, when Kenneth Paschal won a Shelby County special election to become the first Black Republican elected to the Alabama House since Reconstruction.

Kay Ivey

Even as the Republican Party has dominated local and statewide voting—98 of 140 total legislative seats were in GOP hands in 2017—governance has not proven to be smooth or effective. While various polls indicate Alabama is the most or one of the most politically conservative states in the country, other metrics indicate not much has changed with Republican ascendancy in terms of the state’s place in national rankings of education, public health, or state income. Ethical and personal scandals drove Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore, Speaker of the House Mike Hubbard, and Gov. Robert Bentley from office all within the course of a calendar year. One result was the state’s first Republican female governor, Kay Ivey. Other results, including party realignment or electoral gains by the Democratic Party, seem possible, but unlikely. By the second decade of the twenty-first century, the Republican Party was typically supported by white males, economic elites, evangelicals, and individuals who identify themselves as socially and fiscally conservative. A notable exception occurred in 2021, when Kenneth Paschal won a Shelby County special election to become the first Black Republican elected to the Alabama House since Reconstruction.

Additional Resources

Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

Frederick, Jeff. Stand Up for Alabama: Governor George Wallace. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Key, V. O. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Knopf, 1949.

Webb, Samuel L. Two‑Party Politics in the One‑Party South: Alabama’s Hill Country, 1874-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.