Black Baptists in Alabama

Black Baptists in Alabama have their roots in the days of slavery. Spiritual leaders among black Baptists reached out beyond their communities to the statewide and national stage, playing key roles in improving education, increasing racial equality, and winning civil rights legislation. In addition, black Baptists initiated a faith that helped blacks cope with slavery, segregation, and discrimination. Black Baptist churches also provided, through their worship and community life, a sense of self-esteem in a society that often denied African Americans dignity and worth.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

The Baptist faith first gained a following among African Americans in Alabama during the period of slavery. Some blacks accepted Christianity as introduced to them by slaveowners and by Baptist missionaries and pastors. Many who came from other southern states, such as Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, had already become Baptists and brought the faith with them. Slaves in Alabama and in the South generally worshipped in two different settings: by themselves, in what scholars have termed the “invisible church” in their living quarters, or in secret meetings at designated areas. They also attended the “visible church” in which whites observed blacks in worship, and enslaved people often accompanied their Baptist slaveowners to churches that they attended. As the Baptist effort to convert the enslaved increased and more enslaved people became members of white churches, white and black Baptists formed “branch” churches or sub-congregations in which blacks worshipped by themselves under the supervision of white Baptist churches. Whites also allowed blacks to form a few semi-independent churches in the state, such as Mobile‘s Stone Street Baptist Church and Selma‘s St. Phillips Street Baptist Church. Both churches were founded by enslaved and free blacks in the early nineteenth century and chose their own pastors and lay leaders.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

The Baptist faith first gained a following among African Americans in Alabama during the period of slavery. Some blacks accepted Christianity as introduced to them by slaveowners and by Baptist missionaries and pastors. Many who came from other southern states, such as Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina, had already become Baptists and brought the faith with them. Slaves in Alabama and in the South generally worshipped in two different settings: by themselves, in what scholars have termed the “invisible church” in their living quarters, or in secret meetings at designated areas. They also attended the “visible church” in which whites observed blacks in worship, and enslaved people often accompanied their Baptist slaveowners to churches that they attended. As the Baptist effort to convert the enslaved increased and more enslaved people became members of white churches, white and black Baptists formed “branch” churches or sub-congregations in which blacks worshipped by themselves under the supervision of white Baptist churches. Whites also allowed blacks to form a few semi-independent churches in the state, such as Mobile‘s Stone Street Baptist Church and Selma‘s St. Phillips Street Baptist Church. Both churches were founded by enslaved and free blacks in the early nineteenth century and chose their own pastors and lay leaders.

Enslaved people developed a distinctive form of Christianity that blended African and evangelical characteristics and traditions, especially those practiced by Baptist evangelicals. As a result, the type of Baptist faith that emerged among African Americans emphasized conversion, the Holy Spirit, and baptism, features similar to those of the Baptist faith practiced by white Alabamians. The theme of liberation was also important, but it was generally not shared by white Alabama Baptists, who had a vested interest in supporting the institution of slavery. The enslaved often compared their own plight with that of the enslaved Israelites in the Old Testament. They believed that God would free them as he had the Israelites.

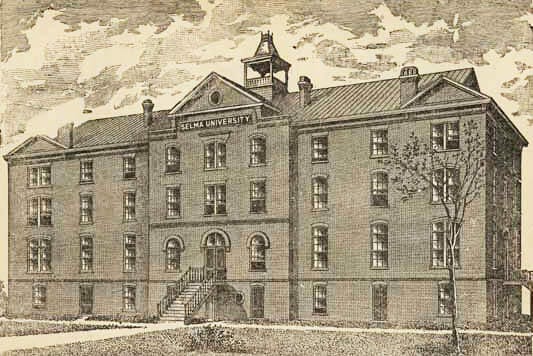

Selma University

Music, in the form of spirituals, was a very significant part of the Black Baptist faith and served to reinforce the themes of deliverance and salvation. Enslaved preachers generally led worship in slave quarters, but a few black ministers received ordination and licensing from white Baptist churches and led worship in the “branch” churches, often preaching to both blacks and whites. Many of these men would become leaders in the African American communities after emancipation, when freed blacks formed their own churches and appointed their religious leaders as pastors. Although churches were generally impoverished and offered worshippers only primitive conditions, they immediately became the central institutions within the black community. Pastors emerged not only as religious leaders but also as social and civic leaders. In 1868 black Baptist pastors came together in Montgomery, Montgomery County, and formed the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention to develop and oversee rules of order and establish mission and education programs. Convention founders then returned to their local communities and established associations to provide fellowship among churches as well as oversee doctrine and practice in local communities.

Selma University

Music, in the form of spirituals, was a very significant part of the Black Baptist faith and served to reinforce the themes of deliverance and salvation. Enslaved preachers generally led worship in slave quarters, but a few black ministers received ordination and licensing from white Baptist churches and led worship in the “branch” churches, often preaching to both blacks and whites. Many of these men would become leaders in the African American communities after emancipation, when freed blacks formed their own churches and appointed their religious leaders as pastors. Although churches were generally impoverished and offered worshippers only primitive conditions, they immediately became the central institutions within the black community. Pastors emerged not only as religious leaders but also as social and civic leaders. In 1868 black Baptist pastors came together in Montgomery, Montgomery County, and formed the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention to develop and oversee rules of order and establish mission and education programs. Convention founders then returned to their local communities and established associations to provide fellowship among churches as well as oversee doctrine and practice in local communities.

Reconstruction was also a time of increased political activity in Alabama’s black community after enfranchisement. Given their general emphasis on liberation theology and a holistic view of the church’s role in the community, it is not surprising that black Baptist ministers were among the political leaders and office holders during this period. In some cases their churches provided a base for political activities. Some laymen and pastors became Alabama state legislators, and others held local offices. Although the post-war Reconstruction Era was of relatively brief duration, black Baptists emerged as the fastest-growing denomination in Alabama and throughout the South.

The era following Reconstruction, from 1874 to 1900, proved to be the formative period for Alabama’s black Baptists. During this time, the number of black Baptist churches and associations increased at an unprecedented rate. New churches arose as blacks migrated to new communities and established their own congregations, and these in turn sparked the creation of many new local church associations to meet the needs of members. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention boasted 76 affiliated associations that in turn represented 1,846 churches with an aggregate membership of 186,000, making it one of the largest state conventions in the nation. The convention also founded several auxiliary agencies, including a mission board, the Sunday School Convention, the Baptist Young People’s Training Union, and the Baptist Leader, the state convention newspaper and official organ.

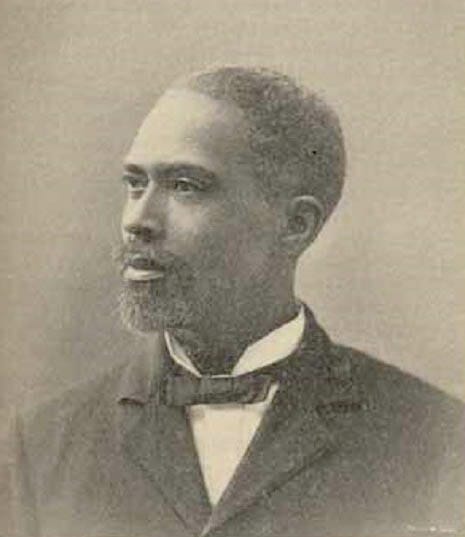

Edward M. Brawley

One of the most ambitious projects of Alabama’s black Baptists was the establishment of Selma University, which opened in 1878. Like other state black Baptist conventions, the Baptists of Alabama were concerned about the poor quality of public education provided to blacks in the South, and like so many other state conventions established colleges. Selma University was unique in that it was one of the few black Baptist colleges founded in the last decades of the nineteenth century that was initiated almost solely by blacks. Discussion surrounding the creation of Selma University began in 1873 when Rev. William McAlpine made a motion at the annual convention meeting in Tuscaloosa to establish a school of theology. In 1877, the convention chose Selma as the site for the college, and the school opened on January 1, 1878, as the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School. Prior to its opening, the school’s four initial students took classes in the Saint Phillips Street Baptist Church. Harrison Woodsmall, a white American missionary, served as the first president. In 1885, the school became Alabama Baptist State University. The name was changed to Selma University in 1905 and has remained thus to the present.

Edward M. Brawley

One of the most ambitious projects of Alabama’s black Baptists was the establishment of Selma University, which opened in 1878. Like other state black Baptist conventions, the Baptists of Alabama were concerned about the poor quality of public education provided to blacks in the South, and like so many other state conventions established colleges. Selma University was unique in that it was one of the few black Baptist colleges founded in the last decades of the nineteenth century that was initiated almost solely by blacks. Discussion surrounding the creation of Selma University began in 1873 when Rev. William McAlpine made a motion at the annual convention meeting in Tuscaloosa to establish a school of theology. In 1877, the convention chose Selma as the site for the college, and the school opened on January 1, 1878, as the Alabama Baptist Normal and Theological School. Prior to its opening, the school’s four initial students took classes in the Saint Phillips Street Baptist Church. Harrison Woodsmall, a white American missionary, served as the first president. In 1885, the school became Alabama Baptist State University. The name was changed to Selma University in 1905 and has remained thus to the present.

Since its founding, Selma University has been the main focus of the convention. But it was not the only educational project of the convention following Reconstruction. Local associations that included Baptist churches in local areas also established schools to provide education for their constituents. Beginning in 1874, with conservative Democrats in control of the Alabama legislature, public schools for blacks received a disproportionately small share of the already inadequate education budget. High schools were non-existent for blacks in Alabama. Baptist leaders called on black Baptists to sacrifice by donating money from their meager earnings so that their children might have a decent education. Existing records indicate at least 30 associational schools were formed in the state between 1875 and 1915. Some of these institutions provided ministerial training in addition to secular education. Education for black Baptists in Alabama received a boost with the formation of the Alabama Women’s State Convention in 1886 by a group of women from Baptist churches in Alabama. Edward M. Brawley, then president of Selma University, was the leading figure in the convention’s formation. Influenced by William J. Simmons, who established a women’s convention in Kentucky to support State University of Kentucky, Brawley sought to organize a similar convention to support his school. After visiting the Kentucky Women’s Convention, Brawley returned to Selma and called an organizational meeting. The purpose of the convention as stated in its original constitution was “to promote the cause of Christ by working to enhance Selma University and by engaging in as much mission work as possible.”

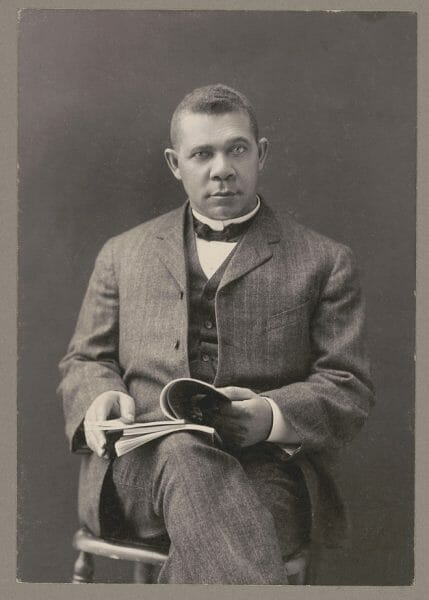

Booker T. Washington

With the passage of Alabama’s 1901 Constitution, blacks in Alabama were legally disfranchised and subjected to legal segregation in virtually every area of their lives. Despite these new forms of oppression, black Baptist churches and associations continued to increase in number. Black Baptists joined a chorus of protest coming from Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington and other prominent black business and civic leaders, and Baptist pastors helped lead boycotts against newly segregated street car lines in both Montgomery and Mobile in 1901 and 1902. Black Baptist religious leaders concerned themselves more with disfranchisement than with segregation, however, and were involved in two of the four petitions protesting the actions of the 1901 Constitutional Convention, which disfranchised blacks and poor whites.

Booker T. Washington

With the passage of Alabama’s 1901 Constitution, blacks in Alabama were legally disfranchised and subjected to legal segregation in virtually every area of their lives. Despite these new forms of oppression, black Baptist churches and associations continued to increase in number. Black Baptists joined a chorus of protest coming from Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington and other prominent black business and civic leaders, and Baptist pastors helped lead boycotts against newly segregated street car lines in both Montgomery and Mobile in 1901 and 1902. Black Baptist religious leaders concerned themselves more with disfranchisement than with segregation, however, and were involved in two of the four petitions protesting the actions of the 1901 Constitutional Convention, which disfranchised blacks and poor whites.

During the early twentieth century, many blacks moved to urban areas, and black Baptists sought to minister to these communities by building institutional churches that met both the spiritual and secular needs of recent black migrants. For example, Day Street Baptist Church in Montgomery provided worship each Sunday, offered Sunday school instruction, and oversaw the Baptist Young Peoples Union, the Dorcas Sewing Circle (for girls), the Cadet Department (for boys), a burial society, and a job-finding service. Black ministers supported local businesses and promoted the growth of the black business community. Following the lead of earlier entrepreneurs such as Birmingham native W. R. Pettiford, some pastors formed economic institutions such as banks and insurance companies and established newspapers. In urban settings black Baptist churches provided a haven and support network for those adjusting to city life. Well-known pastors in Birmingham were summoned to the factories of emerging industries in the city to lecture to blacks on the importance of working around the clock in those facilities rather than taking off on Saturdays and Sundays, as they had done in the rural areas from which they came. Music remained an important aspect of black Baptist worship, and the gospel choirs and soloists that had emerged during the depression years of the 1930s increased in popularity in the mid-twentieth century. This music reflected the people’s culture and pride and added to the emotional fervor and celebratory worship important in most black Baptist churches. Revivals continued to be a very important activity in churches and the chief means of evangelism.

Despite its growth, the state convention struggled to maintain adequate funding for its departments and auxiliaries. Education remained the convention’s major thrust, and the preservation of Selma University was its primary objective. Although most of the other 30 academies closed when black public high schools opened in the state, Birmingham Baptist College, which had been formed by black Baptists of Birmingham in 1904 primarily to train its ministers and laymen, continued to provide high school courses, as did Cedar Grove Academy in Mobile.

William Reuben Pettiford

World War II was a turning point for blacks in Alabama and the nation. African Americans became more dissatisfied with their own lack of freedom at home as they fought for the freedom of others abroad. Black Baptist pastors and leaders became an essential part of the new militancy while maintaining their traditional roles as spiritual leaders and builders and preservers of institutions in the community. Past calls for accommodation and patience gave way to demands for immediate elimination of inequalities. For example, in 1950 at the meeting of the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention, the Reverend M. W. Whitt, chairman of the mission board, lashed out against segregated churches as city officials and several white pastors sat in the audience. Not only did pastors express their displeasure through speeches and sermons, they also began to support movements such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Several became leaders of local chapters in their communities.

William Reuben Pettiford

World War II was a turning point for blacks in Alabama and the nation. African Americans became more dissatisfied with their own lack of freedom at home as they fought for the freedom of others abroad. Black Baptist pastors and leaders became an essential part of the new militancy while maintaining their traditional roles as spiritual leaders and builders and preservers of institutions in the community. Past calls for accommodation and patience gave way to demands for immediate elimination of inequalities. For example, in 1950 at the meeting of the Alabama Colored Baptist State Convention, the Reverend M. W. Whitt, chairman of the mission board, lashed out against segregated churches as city officials and several white pastors sat in the audience. Not only did pastors express their displeasure through speeches and sermons, they also began to support movements such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Several became leaders of local chapters in their communities.

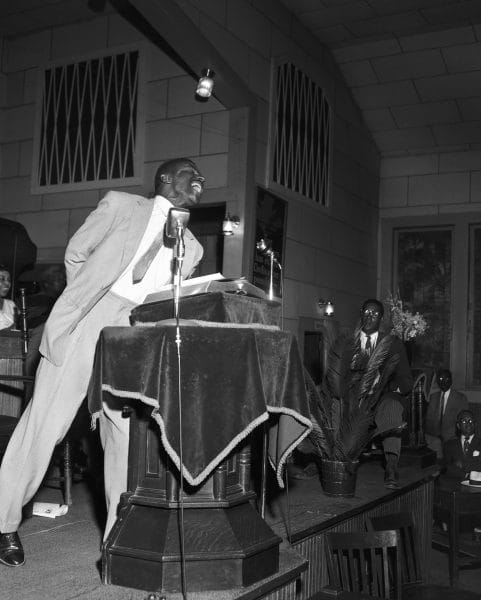

Among the pastors who took a militant stance, Vernon Johns, pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, was one of the most outspoken. As a student at Oberlin College’s School of Theology, Johns became acquainted with the Social Gospel, a Christian philosophy that the teachings of Jesus must be applied to problems and evils in society. After serving as pastor of several churches and a small Baptist college in Virginia, Johns became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. From the pulpit, Johns preached to inspire members to fight segregation and discrimination. In addition to militant sermons, Johns also defied Montgomery’s segregation laws. Although Johns’ pastorate was short, he did inspire a group of women who attended Dexter to form the Women’s Political Council. Most of all, Johns’ ministry helped instill a social consciousness among some Dexter members that his successor, Martin Luther King, Jr., could build on.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

Alabama’s black Baptists took a leading role in the civil rights struggle in the state and in the nation at large. Black Baptist pastors spearheaded movements in their local communities, and their churches provided funds, charismatic leaders, spiritual inspiration, and protestors for the major campaigns in Alabama. Because of the actions in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma, all led by black Baptist Alabama pastors, both the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, became law. Although pastors from other denominations participated, the state’s black Baptist pastors, such as Fred Shuttlesworth and Ralph David Abernathy, emerged as the primary leaders. Several factors contributed to their leadership role. For example, the sheer number and size of Baptist congregations offered their pastors great prestige and influence. Furthermore, most black Baptist pastors were free from white economic control because they received their livelihood from black congregations. Whereas pastors of other denominations were frequently hampered by conservative bishops or other church officials, black Baptist ministers were responsible only to their local congregations, which generally appreciated and openly supported their civil-rights involvement.

Fred Lee Shuttlesworth

Alabama’s black Baptists took a leading role in the civil rights struggle in the state and in the nation at large. Black Baptist pastors spearheaded movements in their local communities, and their churches provided funds, charismatic leaders, spiritual inspiration, and protestors for the major campaigns in Alabama. Because of the actions in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma, all led by black Baptist Alabama pastors, both the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, became law. Although pastors from other denominations participated, the state’s black Baptist pastors, such as Fred Shuttlesworth and Ralph David Abernathy, emerged as the primary leaders. Several factors contributed to their leadership role. For example, the sheer number and size of Baptist congregations offered their pastors great prestige and influence. Furthermore, most black Baptist pastors were free from white economic control because they received their livelihood from black congregations. Whereas pastors of other denominations were frequently hampered by conservative bishops or other church officials, black Baptist ministers were responsible only to their local congregations, which generally appreciated and openly supported their civil-rights involvement.

Since the civil-rights movement, black Baptists have been primarily concerned with expanding the political and civil rights of African Americans in the state and preserving the institutions of the denomination. Except for providing tenure for officers, the convention has made few changes. Education remains the primary emphasis. Baptist schools in Birmingham and Mobile continue to make progress and serve vital needs in those communities. Coincidentally, the state convention has struggled to keep the doors of Selma University open, a task that continues to dominate much of its life and energy.

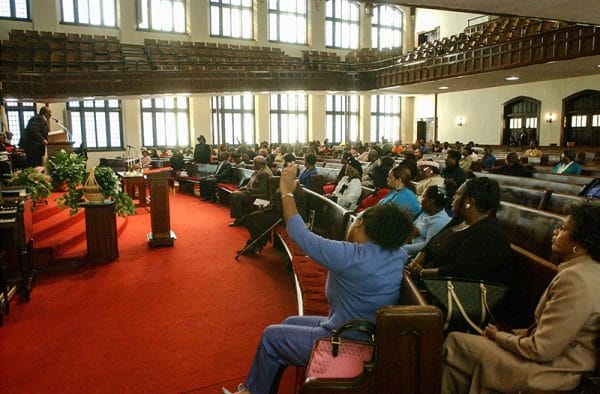

Abyssinia Baptist Church

Meanwhile, relations between black and white Baptists have improved somewhat. During Reconstruction, the two groups shared very little communication and few working relationships. Beginning in the 1950s, although black and white Baptist often disagreed over the civil rights movement, they began to work together in mission and evangelistic projects. Black Baptist churches were allowed to become members of the Southern Baptist Convention. However, black and white Baptists continue to be divided over social, cultural, and political issues. For example, Southern Baptists tend to favor a limited role for government and increasingly support the Republican Party. Blacks tend to favor a more activist role for government and vote the Democratic Party ticket. Some Southern Baptist churches in the state remain segregated. Alabama black Baptists remain today the largest denomination in the state among African Americans. There are 100 associations and three conventions, with a church membership that is estimated to be approximately 450,000. Many churches continue to grow, but some rural churches have declined because of relocation to cities. Black Baptist churches can be found all over the state and cater to all people of all income levels and social circumstances. Despite their continuing success, black Baptist churches face several challenges. Among these are whether or not women should become ministers and pastors; inroads made by Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostals, and other sects and religious groups; challenges from so-called “health and wealth” churches, which promote financial and health benefits to attendees; stewardship within the denomination; and new styles of music and worship. The success and growth of the black Baptist faith in Alabama will depend on how it can respond to these challenges.

Abyssinia Baptist Church

Meanwhile, relations between black and white Baptists have improved somewhat. During Reconstruction, the two groups shared very little communication and few working relationships. Beginning in the 1950s, although black and white Baptist often disagreed over the civil rights movement, they began to work together in mission and evangelistic projects. Black Baptist churches were allowed to become members of the Southern Baptist Convention. However, black and white Baptists continue to be divided over social, cultural, and political issues. For example, Southern Baptists tend to favor a limited role for government and increasingly support the Republican Party. Blacks tend to favor a more activist role for government and vote the Democratic Party ticket. Some Southern Baptist churches in the state remain segregated. Alabama black Baptists remain today the largest denomination in the state among African Americans. There are 100 associations and three conventions, with a church membership that is estimated to be approximately 450,000. Many churches continue to grow, but some rural churches have declined because of relocation to cities. Black Baptist churches can be found all over the state and cater to all people of all income levels and social circumstances. Despite their continuing success, black Baptist churches face several challenges. Among these are whether or not women should become ministers and pastors; inroads made by Jehovah’s Witnesses, Pentecostals, and other sects and religious groups; challenges from so-called “health and wealth” churches, which promote financial and health benefits to attendees; stewardship within the denomination; and new styles of music and worship. The success and growth of the black Baptist faith in Alabama will depend on how it can respond to these challenges.

Additional Resources

Boothe, Charles Octavius. The Cyclopedia of the Colored Baptists of Alabama: Their Leaders and their Work. Birmingham: Alabama Publishing Company, 1895.

Fallin, Wilson, Jr. Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007.

———. The African American Church in Birmingham: A Shelter in the Storm, 1815-1963. New York: Garland Press, 1964.

Minutes of the Alabama Missionary Baptist State Convention. Archives of the Alabama Baptist Historical Society, Samford University, Birmingham, Alabama.

Montgomery, William E. Under Their Own Vine and Fig Tree: The African American Church in the South, 1865-1900. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.