European Exploration and Colonial Period

Fort Toulouse

In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his forces first set foot in what is now Alabama. His arrival marked the beginning of a dramatic cultural shift in the Southeast. From the mid-sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth century, Spain, France, and England vied for control of the region. Native American groups used trade and warfare to play one group against the other, with varying degrees of success. By 1820, Spain, the last of the three contenders, had yielded to the United States. Native American groups, by and large, were in the process of being forced off their lands by the federal government at the urging of white settlers.

Fort Toulouse

In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his forces first set foot in what is now Alabama. His arrival marked the beginning of a dramatic cultural shift in the Southeast. From the mid-sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth century, Spain, France, and England vied for control of the region. Native American groups used trade and warfare to play one group against the other, with varying degrees of success. By 1820, Spain, the last of the three contenders, had yielded to the United States. Native American groups, by and large, were in the process of being forced off their lands by the federal government at the urging of white settlers.

Spanish Exploration

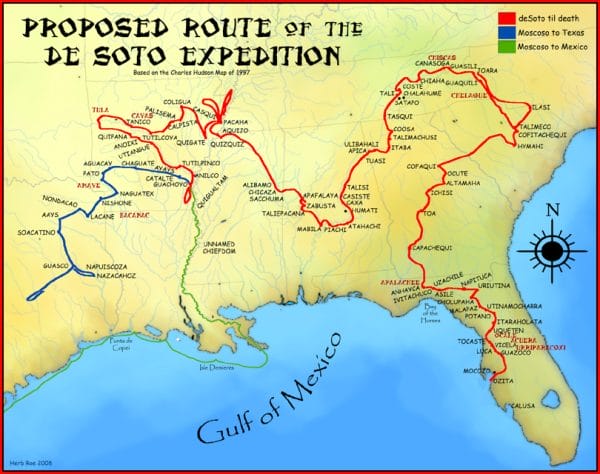

Though not the first Europeans to view present-day Alabama—a distinction due to the expeditions of either Alonso Álvarez de Pineda (1519) or Pánfilo de Narváez (1528)—Soto and his men were the first to explore the interior. The Soto expedition landed on the west coast of the Florida Peninsula on May 30, 1539, with 513 soldiers, their servants, and 237 horses. The force proceeded to terrorize and enslave the region’s Native American inhabitants throughout its march northward toward Apalache (present-day Tallahassee) in quest of gold. After spending the winter at Apalache, the expedition turned northeastward and travelled through present-day Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee. The Spaniards entered Alabama along the Coosa River and followed it to Talisi, most likely to have been located near present-day Childersburg, Talladega County, according to historian Charles Hudson’s widely accepted reconstruction of De Soto’s route. They then headed west along the Alabama River.

Hernando de Soto Route Map

In a province of the Mabila Indians controlled by Chief Tascaluza, an elaborately plumed chieftain refused Soto’s request for bearers and was kept hostage during Soto’s stay. Capture of a town leader would become Soto’s standard method of ensuring cooperation from the town’s inhabitants while he and his men travelled through tribal territories. Understandably, such a tactic aroused great resentment; at one point two Spaniards were slain in an ambush while building rafts to cross the river. Soto held Chief Tascaluza responsible. On the morning of October 18, 1540, Soto’s troops reached the Mabila tribal capital, a palisaded town, presided over by Chief Tascaluza. An encounter between a Spanish officer and a Mabila inhabitant turned violent when the officer perceived that the Indian did not offer him due respect, ending with the Indian’s arm being severed. In the melee that followed, Soto’s men set fire to the town and burned both the town and many of its occupants. Fernández de Biedma, King Carlos I’s agent for the expedition, recorded in his journal, “We killed them all either with fire or the sword.” Soto then continued on to new conflicts in Mississippi, pursuing the legendary gold-filled town of El Dorado until his death on the Mississippi River on March 21, 1542.

Hernando de Soto Route Map

In a province of the Mabila Indians controlled by Chief Tascaluza, an elaborately plumed chieftain refused Soto’s request for bearers and was kept hostage during Soto’s stay. Capture of a town leader would become Soto’s standard method of ensuring cooperation from the town’s inhabitants while he and his men travelled through tribal territories. Understandably, such a tactic aroused great resentment; at one point two Spaniards were slain in an ambush while building rafts to cross the river. Soto held Chief Tascaluza responsible. On the morning of October 18, 1540, Soto’s troops reached the Mabila tribal capital, a palisaded town, presided over by Chief Tascaluza. An encounter between a Spanish officer and a Mabila inhabitant turned violent when the officer perceived that the Indian did not offer him due respect, ending with the Indian’s arm being severed. In the melee that followed, Soto’s men set fire to the town and burned both the town and many of its occupants. Fernández de Biedma, King Carlos I’s agent for the expedition, recorded in his journal, “We killed them all either with fire or the sword.” Soto then continued on to new conflicts in Mississippi, pursuing the legendary gold-filled town of El Dorado until his death on the Mississippi River on March 21, 1542.

Not until late in the next decade did new explorations reach Alabama. Concern over the increasing number of shipwrecks along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico sparked demands for settlements to provide a haven for ships in distress. The new Spanish king, Philip II, gave the authorization and turned the matter over to the viceroy in Mexico, Luis de Velasco, who dispatched sea voyages to seek a suitable site. On September 3, 1558, three vessels under the command of Guido Lavazares (or las Bazares) and piloted by Bernaldo Peloso, a Soto veteran, sailed from the Mexican port of Veracruz. Upon reaching Mobile Bay, the captain named it Bahía Filipina (Philip’s Bay), honoring the monarch. He described it as “the largest and most commodious” yet seen. In addition to its deep anchorage, he noted that it offered abundant grass and water for livestock, timber and stone for building, and soil suitable for both brick-making and pottery. The Native American towns along the shore boasted fields of corn, beans, and pumpkins, and several inhabitants were seen fishing. A second expedition followed Lavazares’s return to Veracruz in 1558. Led by Juan de Rentería, it explored Mobile and Pensacola bays.

Ordered to establish a colony on the northern shore of the Gulf of Mexico, Tristán de Luna y Arellano sailed into Mobile Bay in July 1559 but shortly moved his fleet on to Pensacola Bay. Two months later, a hurricane destroyed most of his ships and supplies. Luna sent a company north to seek provisions from the local Indians. The force stopped along the Alabama River at a large town called Nanipacana, whose inhabitants fled as the Spaniards approached. The Indians had left behind stores of corn and beans, which the Spaniards raided to replenish their food supplies. The following February, Luna returned to Mobile Bay and began moving his fleet up the Alabama River to the same Indian town, which he renamed Santa María de Nanipacana. By the time the Spaniards reached the settlement, the Indians had fled again, taking their food supply with them. Further reconnaissance revealed only abandoned houses and fields and unsettled country beyond. After unsuccessful attempts to find supplies, Luna, suffering dementia and plagued by mutinous sentiments among his officers, abandoned Nanipacana and returned to Pensacola Bay. Soon afterward, Luna was directed to remove the colony to Santa Elena (near present-day Port Royal, South Carolina) on the Atlantic coast.

Senkaitschi, Yuchi Leader

After a long period of disinterest in the northern Gulf Coast, the Spaniards resumed their explorations in 1686 in an effort to find and destroy a French colony established by Robert Cavelier de La Salle somewhere on the Gulf Coast. In February, a voyage captained by Juan Enríquez Barroto ran the coast from the Florida Keys and dropped anchor off Mobile Point. The men then spent two weeks exploring Mobile Bay. This expedition was followed by that of Marcos Delgado, who was charged by the Spanish governor of Florida with finding the French colony, believed to be located on the lower Mississippi River. Delgado’s force marched past Apalache, then turned away from the coast, hacking its way through tangled wilderness past present-day Dothan, Houston County, and the Spring Hill neighborhood of Mobile County. The men reached a Chacato Indian town called Aqchay along the Alabama River near present-day Selma, Dallas County, then travelled upstream to the Alabama Indian towns of Tabasa and Culasa. After spending time in Yuchi, Choctaw, and Cherokee towns, Delgado made contact with Mabila chiefs. He claimed to have effected peace among the various tribes before turning back.

Senkaitschi, Yuchi Leader

After a long period of disinterest in the northern Gulf Coast, the Spaniards resumed their explorations in 1686 in an effort to find and destroy a French colony established by Robert Cavelier de La Salle somewhere on the Gulf Coast. In February, a voyage captained by Juan Enríquez Barroto ran the coast from the Florida Keys and dropped anchor off Mobile Point. The men then spent two weeks exploring Mobile Bay. This expedition was followed by that of Marcos Delgado, who was charged by the Spanish governor of Florida with finding the French colony, believed to be located on the lower Mississippi River. Delgado’s force marched past Apalache, then turned away from the coast, hacking its way through tangled wilderness past present-day Dothan, Houston County, and the Spring Hill neighborhood of Mobile County. The men reached a Chacato Indian town called Aqchay along the Alabama River near present-day Selma, Dallas County, then travelled upstream to the Alabama Indian towns of Tabasa and Culasa. After spending time in Yuchi, Choctaw, and Cherokee towns, Delgado made contact with Mabila chiefs. He claimed to have effected peace among the various tribes before turning back.

Enríquez Barroto again visited Mobile Bay in 1687 as chief pilot and diarist for Antonio Rivas and Pedro de Iriarte, who sent men in canoes to explore the bay to the mouth of the Mobile River. An additional expedition, captained by Andrés de Pez and Francisco López de Gamarra, took soundings of Mobile Bay that same year. In 1688, the bay was further explored by Pez and Enríquez Barroto, still seeking the elusive La Salle. Fear of French encroachment combined with an ever-growing threat of incursion by the English spurred the Spanish occupation of Pensacola Bay in 1698. Indeed, on January 26, 1699, four French ships captained by Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville appeared offshore before the Pensacola settlement. Spain’s fears of a French presence in the region at once were justified.

French Exploration and Settlement

On January 31, d’Iberville’s ships anchored off Mobile Point, sounded the channel, and explored present-day Dauphin Island, naming it Île du Massacre (Massacre Island) for the 60 human skeletons they found there. Iberville himself went ashore west of the bay, noting recently abandoned Indian huts. The ships then sailed west and anchored in Mississippi Sound. While Iberville explored the Mississippi River, his men began construction of Fort Maurepas on Biloxi Bay.

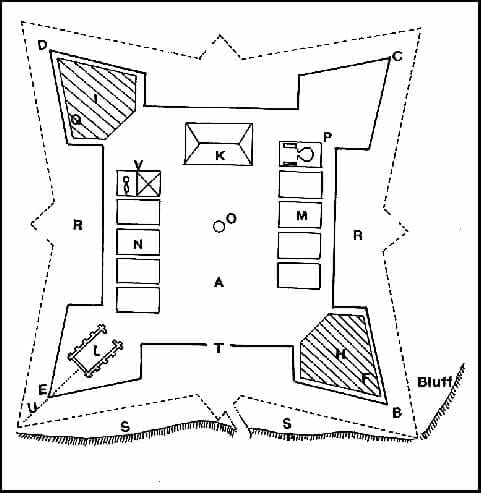

Fort Maurepas Diagram

A storm prior to his return to France emphasized to Iberville the need for a more secure anchorage. After additional exploration, his men found a deeper passage between present-day Dauphin Island and Mobile Point that had been overlooked on the initial reconnaissance. Iberville had left orders for further exploration of the Mobile River with a view to relocating the Fort Maurepas settlement farther inland. His younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, second in command of Fort Maurepas, explored the Mobile and Tombigbee rivers, seeking a suitable site. He settled on a location approximately 25 miles inland on a bluff on the Mobile River’s west bank. He then oversaw construction of Fort Louis de La Louisiane, which stood from 1702 to 1711, when the colony relocated to present-day Mobile. During this period, Henri de Tonti, who had been La Salle’s lieutenant in Illinois, made peace overtures to leaders of nearby Tomeh, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Indian towns in an effort to counter a growing English influence. The early French presence in the region was recorded in some detail in ship’s carpenter André Pénigaut‘s Annals of Louisiana from 1698 to 1722.

Fort Maurepas Diagram

A storm prior to his return to France emphasized to Iberville the need for a more secure anchorage. After additional exploration, his men found a deeper passage between present-day Dauphin Island and Mobile Point that had been overlooked on the initial reconnaissance. Iberville had left orders for further exploration of the Mobile River with a view to relocating the Fort Maurepas settlement farther inland. His younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, second in command of Fort Maurepas, explored the Mobile and Tombigbee rivers, seeking a suitable site. He settled on a location approximately 25 miles inland on a bluff on the Mobile River’s west bank. He then oversaw construction of Fort Louis de La Louisiane, which stood from 1702 to 1711, when the colony relocated to present-day Mobile. During this period, Henri de Tonti, who had been La Salle’s lieutenant in Illinois, made peace overtures to leaders of nearby Tomeh, Choctaw, and Chickasaw Indian towns in an effort to counter a growing English influence. The early French presence in the region was recorded in some detail in ship’s carpenter André Pénigaut‘s Annals of Louisiana from 1698 to 1722.

When war erupted in 1719 in Europe, with Spain and France on opposing sides, the French seized Spanish Pensacola, which passed back and forth from France to Spain until the war’s end. In 1763, at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in North America), France lost all of its North American territories. Spain, France’s ally in the conflict, took possession of former French territories west of the Mississippi River, and the victorious British took everything east of the river, excepting Ile d’Orleans, which was retained by Spain, and established the colony of British West Florida.

British Exploration and Settlement

In 1764, the British Admiralty appointed George Gauld to survey the coasts and waterways of the British Floridas, which at the time included the present states of Mississippi and Alabama, as well as the Florida panhandle. In 1768, he surveyed and sounded lower Mobile Bay, and his work, ended by the American Revolution, represented the most advanced and extensive cartographic survey of any part of the Gulf Coast to that time.

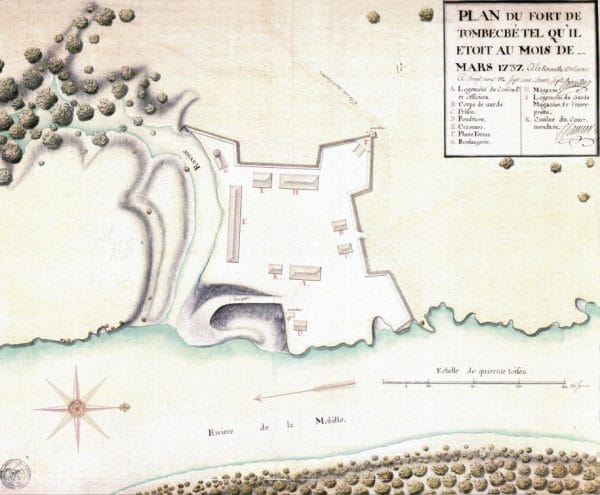

Fort Tombecbe, 1737

Additional surveys were carried out by Thomas Hutchins and Bernard Romans. Hutchins, assisting the chief engineer of the British army in North America, began work in 1766. He inspected military installations at Mobile and Pensacola. Romans charted and mapped the coasts and offshore islands of British West Florida, traveling northwest on horseback from Mobile to Chickasaw country in Mississippi. He later recounted his travels in a book that included maps of the region as well as drawings of the region’s flora. In 1776, botanist William Bartram made a solitary trip from Tensaw Bluff to the Tombigbee River and the bluff that held the ruins of what he identified merely as “the old French fort,” evidently the short-lived Fort Tombecbe established by Bienville among the Choctaw.

Fort Tombecbe, 1737

Additional surveys were carried out by Thomas Hutchins and Bernard Romans. Hutchins, assisting the chief engineer of the British army in North America, began work in 1766. He inspected military installations at Mobile and Pensacola. Romans charted and mapped the coasts and offshore islands of British West Florida, traveling northwest on horseback from Mobile to Chickasaw country in Mississippi. He later recounted his travels in a book that included maps of the region as well as drawings of the region’s flora. In 1776, botanist William Bartram made a solitary trip from Tensaw Bluff to the Tombigbee River and the bluff that held the ruins of what he identified merely as “the old French fort,” evidently the short-lived Fort Tombecbe established by Bienville among the Choctaw.

Bernardo de Gálvez

In May 1779, Spain entered the Revolutionary War on the side of the American colonies. Bernardo de Gálvez, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, and his commander José Manuel de Ezpeleta overran British posts along the Mississippi River and reclaimed Mobile and Pensacola. It was from his efforts that Spain was able to reclaim the territory east of the Mississippi, which it had lost previously to Great Britain. In 1783, Spain formally organized its colony of West Florida (Florida Occidental in Spanish), with garrisons throughout the contemporary Southeast; sites in present-day Alabama included Fort Confederation (the renamed Fort Tombecbe) in Livingston, Sumter County, and for San Esteban in St. Stephens, Washington County. Gálvez’s forces experienced repeated maritime disasters, resulting in part from a lack of accurate maps. While attempting to enter Mobile Bay, for example, his flagship and five other vessels grounded on a sandbar. Such incidents doubtless influenced his call for a new coastal reconnaissance—a task given to José de Evia, an experienced pilot who had taken part in the capture of Mobile. Reaching Mobile Bay in May 1784, Evia visited Mobile Point and Dauphin Island, where he observed the ruins of the French fort. By the time his task was finished in 1786, he had surveyed the coast between the Florida Keys and Tampico, Mexico.

Bernardo de Gálvez

In May 1779, Spain entered the Revolutionary War on the side of the American colonies. Bernardo de Gálvez, the governor of Spanish Louisiana, and his commander José Manuel de Ezpeleta overran British posts along the Mississippi River and reclaimed Mobile and Pensacola. It was from his efforts that Spain was able to reclaim the territory east of the Mississippi, which it had lost previously to Great Britain. In 1783, Spain formally organized its colony of West Florida (Florida Occidental in Spanish), with garrisons throughout the contemporary Southeast; sites in present-day Alabama included Fort Confederation (the renamed Fort Tombecbe) in Livingston, Sumter County, and for San Esteban in St. Stephens, Washington County. Gálvez’s forces experienced repeated maritime disasters, resulting in part from a lack of accurate maps. While attempting to enter Mobile Bay, for example, his flagship and five other vessels grounded on a sandbar. Such incidents doubtless influenced his call for a new coastal reconnaissance—a task given to José de Evia, an experienced pilot who had taken part in the capture of Mobile. Reaching Mobile Bay in May 1784, Evia visited Mobile Point and Dauphin Island, where he observed the ruins of the French fort. By the time his task was finished in 1786, he had surveyed the coast between the Florida Keys and Tampico, Mexico.

The outline of the future state of Alabama began to take shape with Andrew Ellicott’s survey of the boundary between the United States and West Florida, which he conducted between 1796 and 1800. Spain had reluctantly agreed to accept as the line the 31st parallel specified by Great Britain in the treaty ending the Revolutionary War. Pres. George Washington commissioned Ellicott, an experienced surveyor whose accomplishments included marking the Mason-Dixon Line, to work with the Spanish commissioners to fix the boundary. This boundary and the one Ellicott established between Alabama and Florida still define the northern and southern borders of the state.

During the three centuries of European occupation, Alabama had been claimed by three different nations, each of which contributed to the exploration of its territory. As the eighteenth century drew to a close, so did the era of European rule. Within two decades, the territory would be ceded to the United States, which would then determine its future course.

Further Reading

- Bartram, William. The Travels of William Bartram. 1791. New York: Dover, 1951.

- Braund, Kathyrn H., ed. The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s “Travels” and Legacy. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2022.

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Milanich, Jerald T., and Susan Milbrath, eds. First Encounters: Spanish Explorations in the Caribbean and the United States, 1492-1570. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1989.

- Weddle, Robert S. Spanish Sea: The Gulf of Mexico in North American Discovery, 1500-1685. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1985.

- ———. The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea, 1682-1762. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1991.

- ———. Changing Tides: Twilight and Dawn in the Spanish Sea, 1763-1803. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.

- ———. Wilderness Manhunt: The Spanish Search for La Salle. Revised edition. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999.