Julia S. Tutwiler

Julia Tutwiler

Julia Strudwick Tutwiler (1841-1916) was an educator, prison reformer, and writer and an outspoken proponent of education for women. She was closely involved with the founding of institutions that became the University of West Alabama and the University of Montevallo and with innovations in education for women and African Americans during the Jim Crow era. The women’s prison in Wetumpka, Elmore County, bears her name, as do several other public buildings in the state; her poem “Alabama” is immortalized as the official state song.

Julia Tutwiler

Julia Strudwick Tutwiler (1841-1916) was an educator, prison reformer, and writer and an outspoken proponent of education for women. She was closely involved with the founding of institutions that became the University of West Alabama and the University of Montevallo and with innovations in education for women and African Americans during the Jim Crow era. The women’s prison in Wetumpka, Elmore County, bears her name, as do several other public buildings in the state; her poem “Alabama” is immortalized as the official state song.

Born in Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, on August 15, 1841, Julia Tutwiler was the third of eleven children of Henry and Julia Tutwiler. Her father was of German-Swiss ancestry and attended the University of Virginia. In 1831, he took a position as chair of ancient languages at the newly opened University of Alabama (UA). In 1835, he married Julia Ashe, daughter of Pascal Paoli Ashe, the university steward (the equivalent of the business manager today). Two years later, Tutwiler resigned with the rest of the university’s dissatisfied faculty and taught at several small Alabama colleges. In 1847, Tutwiler established the Greene Springs Academy in Hale County, near Havana, where he remained until his death in 1884.

Greene Springs Academy

Julia Tutwiler’s father believed that women were the intellectual equals of men and should be educated as such. He sent his daughter to Philadelphia to a boarding school that was based on the French system of education and offered instruction in modern languages and culture as well as art and music. During the Civil War, Julia returned to Alabama to teach at her father’s school, which remained open because her father was a member of the anti-Secessionist Whig Party. In 1866, Tutwiler attended Vassar College in New York State for a semester but left because of insufficient funds and took a position at Greensboro Female Academy in Greensboro, Hale County. Tutwiler’s niece, future author and poet Martha Strudwick Young, attended both the Greensboro Female Academy and Greene Springs Academy. Appointed principal in 1867, Tutwiler was joined by another woman as co-principal in 1868, but both women resigned the following year, unable to tolerate the school’s poor physical condition. Tutwiler next taught at Greene Springs Academy in Sawyerville until 1872, when she moved to Lexington, Virginia, to be near a brother enrolled at Washington and Lee College. While there, she studied Latin and Greek privately with a professor and earned a teaching certificate. In summer 1873, she and her brother toured Europe. While there, she enrolled in the normal school at the Deaconesses’ Institute at Kaiserswerth, Prussia, near present-day Dusseldorf, Germany. She lived in Berlin for two years and earned a teaching certificate from the Prussian board of education. In addition, she wrote children’s stories and articles for St. Nicholas Magazine and Appleton’s Journal. Returning to Alabama in 1876, she taught languages and literature until 1881 at the Methodist-affiliated Tuscaloosa Female College. During an 1878 leave of absence, she travelled to France and wrote for the National Journal of Education on the Paris Exposition and on French trade schools for women.

Greene Springs Academy

Julia Tutwiler’s father believed that women were the intellectual equals of men and should be educated as such. He sent his daughter to Philadelphia to a boarding school that was based on the French system of education and offered instruction in modern languages and culture as well as art and music. During the Civil War, Julia returned to Alabama to teach at her father’s school, which remained open because her father was a member of the anti-Secessionist Whig Party. In 1866, Tutwiler attended Vassar College in New York State for a semester but left because of insufficient funds and took a position at Greensboro Female Academy in Greensboro, Hale County. Tutwiler’s niece, future author and poet Martha Strudwick Young, attended both the Greensboro Female Academy and Greene Springs Academy. Appointed principal in 1867, Tutwiler was joined by another woman as co-principal in 1868, but both women resigned the following year, unable to tolerate the school’s poor physical condition. Tutwiler next taught at Greene Springs Academy in Sawyerville until 1872, when she moved to Lexington, Virginia, to be near a brother enrolled at Washington and Lee College. While there, she studied Latin and Greek privately with a professor and earned a teaching certificate. In summer 1873, she and her brother toured Europe. While there, she enrolled in the normal school at the Deaconesses’ Institute at Kaiserswerth, Prussia, near present-day Dusseldorf, Germany. She lived in Berlin for two years and earned a teaching certificate from the Prussian board of education. In addition, she wrote children’s stories and articles for St. Nicholas Magazine and Appleton’s Journal. Returning to Alabama in 1876, she taught languages and literature until 1881 at the Methodist-affiliated Tuscaloosa Female College. During an 1878 leave of absence, she travelled to France and wrote for the National Journal of Education on the Paris Exposition and on French trade schools for women.

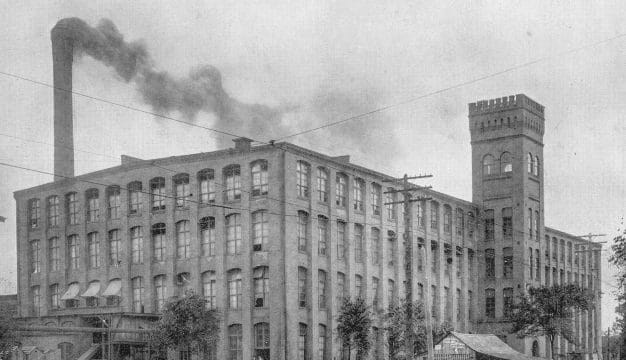

Tuscaloosa Female College

During the winter of 1879 and 1880, Tutwiler organized the Tuscaloosa Benevolent Association (TBA), through which civic-minded women could work to reform conditions in Alabama jails and prisons, an important cause for Tutwiler. An Episcopal convert, she believed that literacy through Bible reading could help inmates avoid repeating their mistakes. Tutwiler also drew on lessons in social activism that she learned at Kaiserswerth. The TBA sent questionnaires to the heads of all county jails, from which they compiled information about their conditions. The association then submitted its findings to the legislature in 1880 and helped to remedy the lack of heat and sanitation in the facilities. Tutwiler and some of her students visited prisons on weekends and conducted religious services, and Tutwiler personally provided Bibles to inmates.

Tuscaloosa Female College

During the winter of 1879 and 1880, Tutwiler organized the Tuscaloosa Benevolent Association (TBA), through which civic-minded women could work to reform conditions in Alabama jails and prisons, an important cause for Tutwiler. An Episcopal convert, she believed that literacy through Bible reading could help inmates avoid repeating their mistakes. Tutwiler also drew on lessons in social activism that she learned at Kaiserswerth. The TBA sent questionnaires to the heads of all county jails, from which they compiled information about their conditions. The association then submitted its findings to the legislature in 1880 and helped to remedy the lack of heat and sanitation in the facilities. Tutwiler and some of her students visited prisons on weekends and conducted religious services, and Tutwiler personally provided Bibles to inmates.

These activities and her strong ties with Alabama clubwomen earned her an appointment as superintendent of prison work for the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). During the 1880s and 1890s, Tutwiler travelled the state on a free pass from the railroad companies as an advocate for WCTU’s principles of education and sobriety. She successfully campaigned for state funding to pay for night school and Sunday school teachers in prisons; the creation of separate prison facilities for women; the establishment of the Alabama Boys’ Industrial School, the South’s first juvenile reform school for white boys; and the appointment of a state prison inspector. She also added her voice to calls for an end to the convict-lease system, under which Alabama prisoners, who were largely African American, were rented out to companies to work in mines and at other dangerous occupations. Such reform efforts won her the nickname “Angel of the Stockade” from both the inmates and the public. Tutwiler, who prior to the Civil War had taught some of her father’s 20 enslaved workers, assisted Tuskegee Institute founder Booker T. Washington in establishing a reform school for African American boys, which opened in 1911.

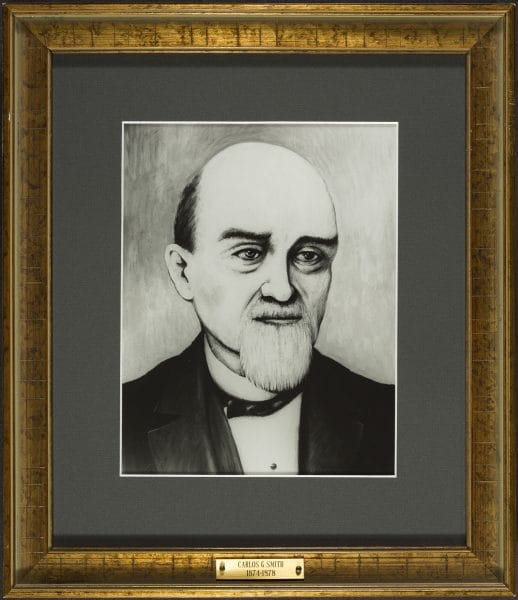

Carlos G. Smith

In 1881, Tutwiler and Carlos G. Smith, her uncle and former UA president, were appointed co-principals of the Livingston Female Academy. The school then consolidated with the Alabama Normal College for Girls and became Livingston Female Academy and State Normal College (now the University of West Alabama). The college received the state government’s first appropriation for women’s education—$2,000 for tuition for 50 students and $500 for school appliances—in exchange for the graduates’ commitment of two years of public school teaching. By 1904, 210 students had graduated from the normal college.

Carlos G. Smith

In 1881, Tutwiler and Carlos G. Smith, her uncle and former UA president, were appointed co-principals of the Livingston Female Academy. The school then consolidated with the Alabama Normal College for Girls and became Livingston Female Academy and State Normal College (now the University of West Alabama). The college received the state government’s first appropriation for women’s education—$2,000 for tuition for 50 students and $500 for school appliances—in exchange for the graduates’ commitment of two years of public school teaching. By 1904, 210 students had graduated from the normal college.

In 1890, Tutwiler became president of the college. She espoused progressive educational theories that students should be treated as individuals and exposed to broad cultural and educational experiences. When asked about their time at the school, students often recalled Tutwiler’s refined voice, penetrating gray eyes, and quiet but absolute authority. Teachers supplemented classroom-based lessons with related visual aids and field trips intended to demonstrate the interconnectedness of the various fields of knowledge. Tutwiler instituted pedagogical methods, such as educational games and simple handicrafts, that she had learned in Germany in a kindergarten department that she established for Livingston’s preschool children. Students also took physiology and learned secretarial skills and dressmaking in addition to attending Bible instruction, religious exercises, and mandatory church on Sunday.

Tutwiler continued to write opinion pieces and, in an 1882 essay in the National Journal of Education, addressed the limited and poorly paid employment opportunities for women despite the shortage of male workers brought on by the Civil War. She advocated for federal and state financing of trade schools modeled on French écoles professionelles, which taught women various skills and handicrafts in addition to a general literary and cultural education. Tutwiler found supporters among Alabama women’s clubs, agricultural groups, and eventually legislators, and in 1893 the state authorized a grant for the Alabama Girls Industrial School at Montevallo (now the University of Montevallo). Though offered its presidency, Tutwiler preferred to remain at the Alabama Normal College.

Alabama Normal College Tennis Team, 1910

Tutwiler accepted the educational and social segregation of African Americans apparently without question, even as she dedicated herself to expanding opportunities for white women. Her campaign to open the University of Alabama to qualified white women succeeded in 1892, when its board of trustees, persuaded by her eloquence, accepted her petition that women 18 years or older be admitted by examination to the sophomore or higher classes. In 1897, women were allowed to enter the freshmen class, and by 1899 the number of women students rose from five to 26 among a student body of 180. In 1907, the university awarded Tutwiler an honorary LL.D., named scholarships in her honor, and in 1915 christened a dormitory Julia Tutwiler Hall.

Alabama Normal College Tennis Team, 1910

Tutwiler accepted the educational and social segregation of African Americans apparently without question, even as she dedicated herself to expanding opportunities for white women. Her campaign to open the University of Alabama to qualified white women succeeded in 1892, when its board of trustees, persuaded by her eloquence, accepted her petition that women 18 years or older be admitted by examination to the sophomore or higher classes. In 1897, women were allowed to enter the freshmen class, and by 1899 the number of women students rose from five to 26 among a student body of 180. In 1907, the university awarded Tutwiler an honorary LL.D., named scholarships in her honor, and in 1915 christened a dormitory Julia Tutwiler Hall.

The always-active Tutwiler also taught at the Chautauqua Assembly in Monteagle, Tennessee, and financed several buildings at this retreat school for religious instructors. Her work as an educator brought recognition from the National Education Association, which elected her one of its directors in 1884 and president of its section on elementary education in 1891. In this capacity, she helped to develop Alabama’s teacher-certification system and establish uniform standards for teacher education. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (also called the Chicago World’s Fair), Tutwiler attended meetings of the Congress of Representative Women of the World and the International Historical Congress of Charities and Corrections, for which she served as the secretary of the Alabama delegation, and she was named honorary vice president of the International Congress of Education. In addition to reading an article at an assembly in the Women’s Building, she was appointed a judge for the World’s Fair Department of Liberal Arts.

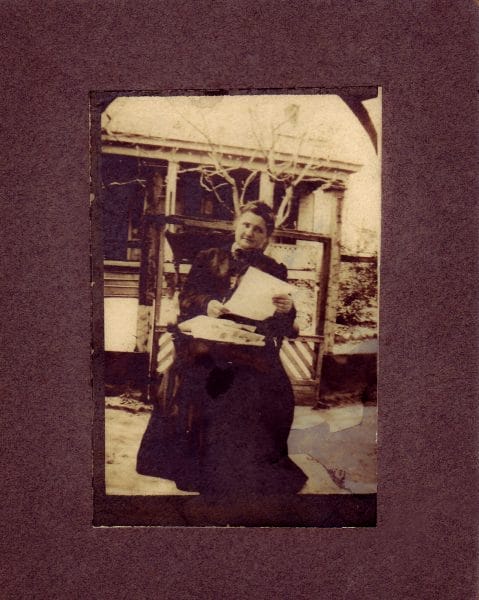

Julia Tutwiler in Livingston

In 1907, the Livingston Normal College came under state control as a result of provisions for regulating public educational institutions included in the Alabama Constitution of 1901. The governor appointed new trustees who criticized Tutwiler’s casual business practices, including her habit of mixing personal money in with the school funds. When they appointed George W. Brock, chair of ancient languages and mathematics, as business manager, Tutwiler protested unsuccessfully to the governor for being displaced. Her impulsive behavior, strong personality, and lack of experience in working with non-family members did not mix well with the new administration and the bureaucratic requirements of the state educational system.

Julia Tutwiler in Livingston

In 1907, the Livingston Normal College came under state control as a result of provisions for regulating public educational institutions included in the Alabama Constitution of 1901. The governor appointed new trustees who criticized Tutwiler’s casual business practices, including her habit of mixing personal money in with the school funds. When they appointed George W. Brock, chair of ancient languages and mathematics, as business manager, Tutwiler protested unsuccessfully to the governor for being displaced. Her impulsive behavior, strong personality, and lack of experience in working with non-family members did not mix well with the new administration and the bureaucratic requirements of the state educational system.

Brock, the new president, antagonized Tutwiler’s devotees by criticizing her record keeping and the inadequacies of the college’s physical plant and student housing. In fact, Tutwiler had generously spent her own money on the residential cottages and loaned money to needy students. Tutwiler retired in 1910 and was named the first president emerita in Alabama and was given $100 a month as a pension, but this was terminated after one year. Soon afterward, Tutwiler developed cancer. Though she was unsuccessful in securing a retirement allowance from the Carnegie Foundation, Alabama clubwomen and several prominent men rallied behind Tutwiler and honored her with portraits, plaques, endowed scholarships, markers, and laudatory essays. On September 14, 1915, the state legislature recognized her contributions.

Tutwiler died in Birmingham on March 24, 1916, leaving $15,000 in a scholarship loan fund. Livingston Normal College’s administration and classroom building was renamed for her. In 1931, the state adopted her poem “Alabama,” which she composed while in Germany, as lyrics to the state song. Designated “Alabama’s First Citizen,” Tutwiler was inducted into the Alabama Hall of Fame (1953) and into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame at Judson College (1970).

Further Reading

- Pannell, Anne Gary, and Dorothea E. Wyatt. Julia S. Tutwiler and Social Progress in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1961.

- Pruitt, Paul M. Jr. “Julia S. Tutwiler: Years of Innocence.” Alabama Heritage 22 (Fall 1991): 37–44, 50.

- ———. “Julia S. Tutwiler: Years of Experience.” Alabama Heritage 23 (Winter 1992): 31–39, 44.

- Synnott, Maria G. “Julia Strudwick Tutwiler.” In Women Educators in the United States, 1820-1993: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook, edited by Maxine Schwartz Seller. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994.